Click here to access the PDF version of the policy brief.

Following a presentation to a House and Senate Education Joint Committee Session in March, an investigation into English Language Learner (ELL) rates in Anchorage and Alaska produced an interesting discovery. Alaskans’ impression of ELL education in our state — and classroom instruction more broadly — may deserve some adjustment.

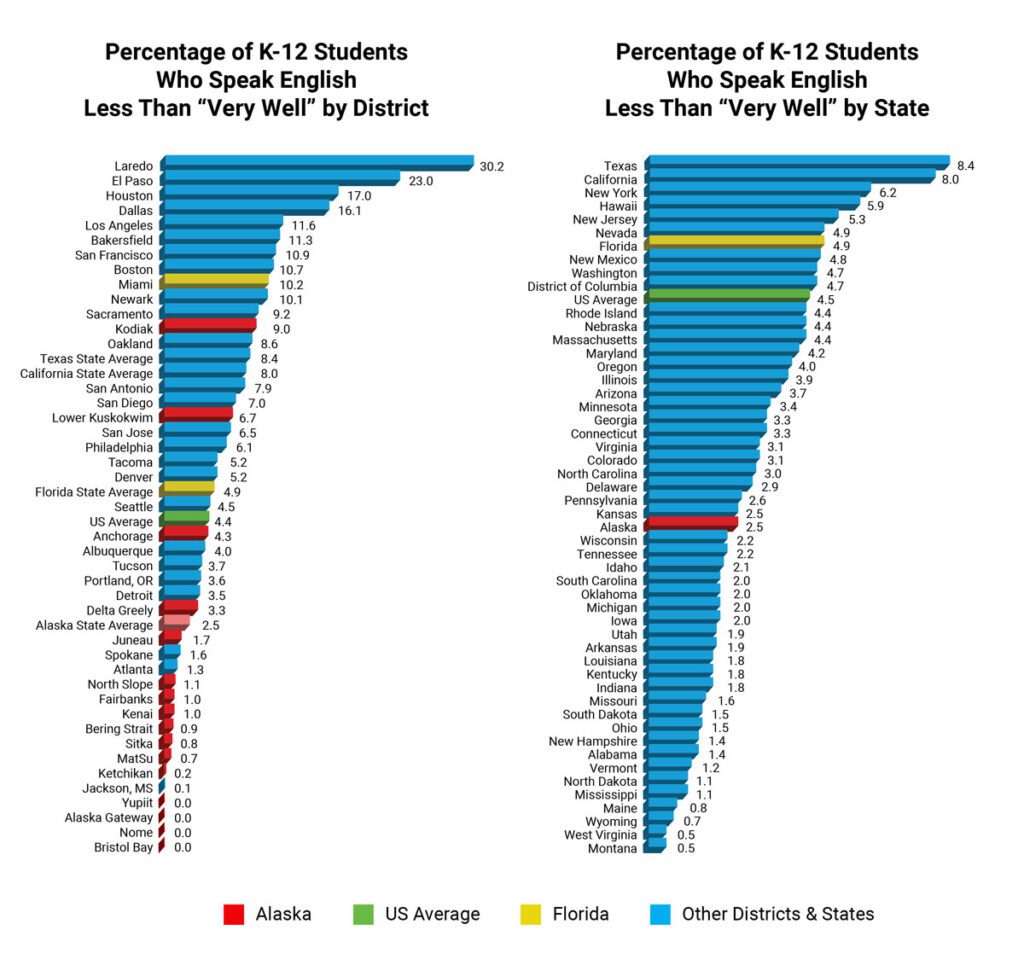

Data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ American Community Survey Education tabulation (NCES ACS-ED) suggest Anchorage and Alaska should have significantly lower ELL burdens than most large cities and states, respectively. Nationally, 4.4% of K–12 students speak English less than “very well,” according to the NCES. Alaska’s percentage of 2.5% ranks 28th among the 50 states and D.C. — right between Kansas and Wisconsin and significantly below all other West Coast states. Yet, 12.1% of students receive ELL services in Alaska, compared to a national average of 10.4%. Something must account for this disconnect.

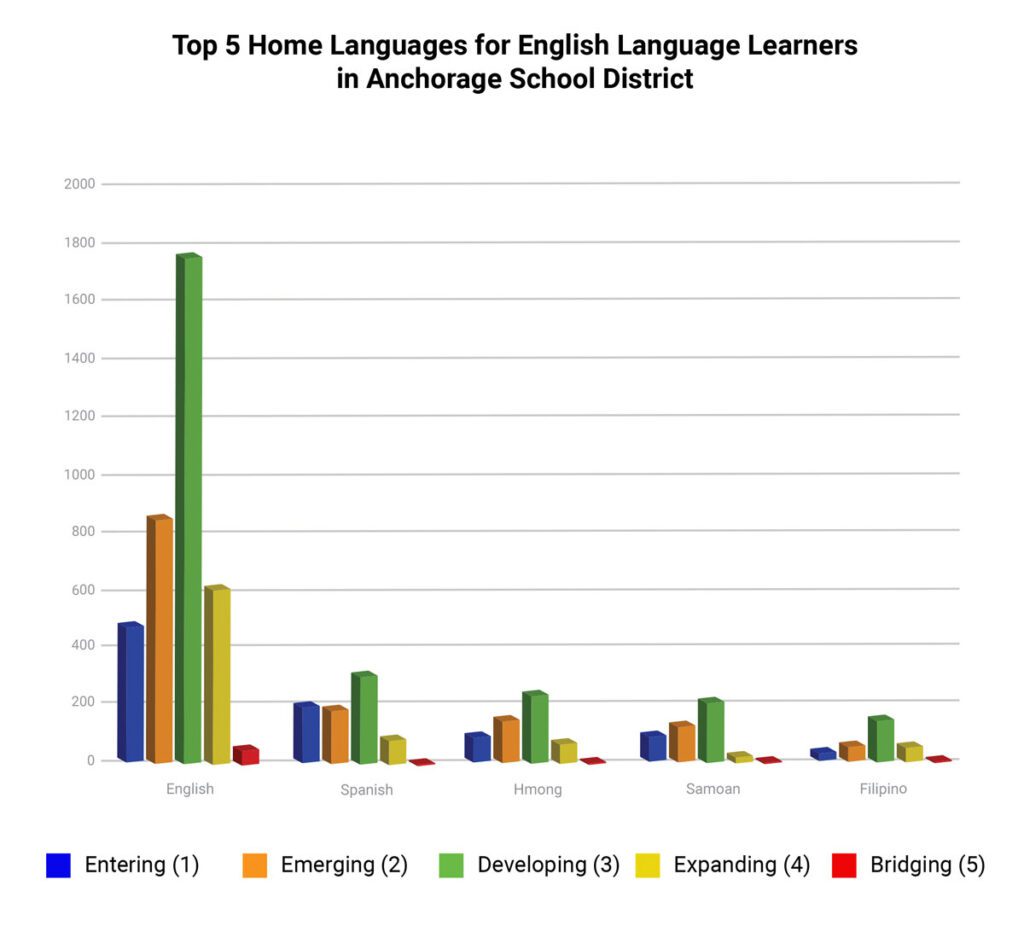

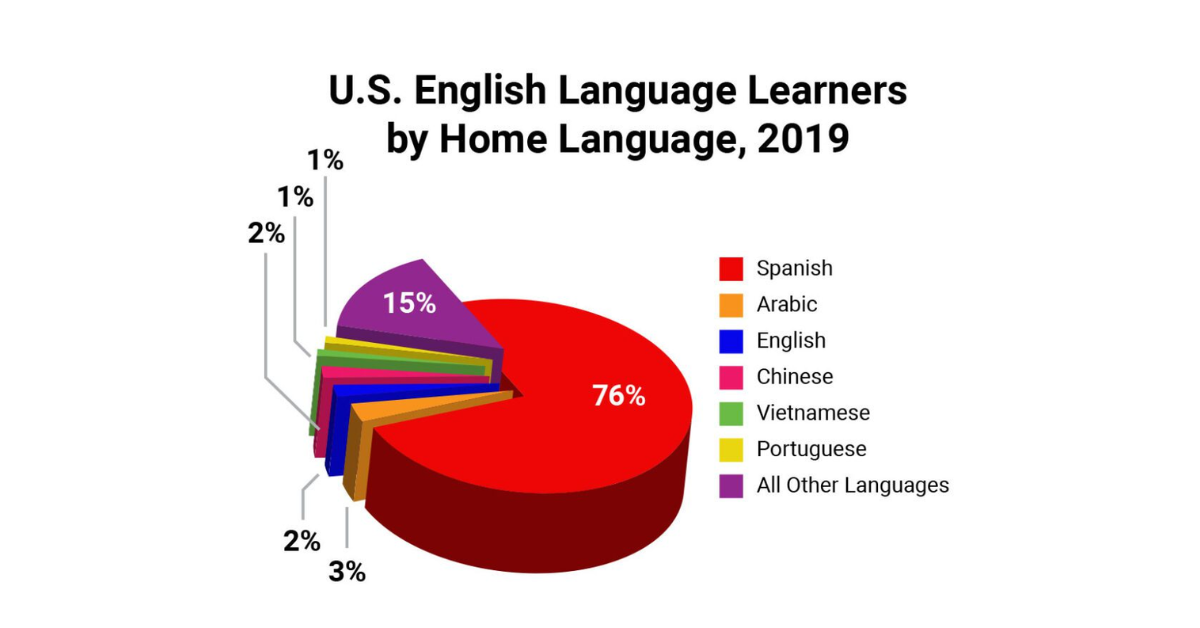

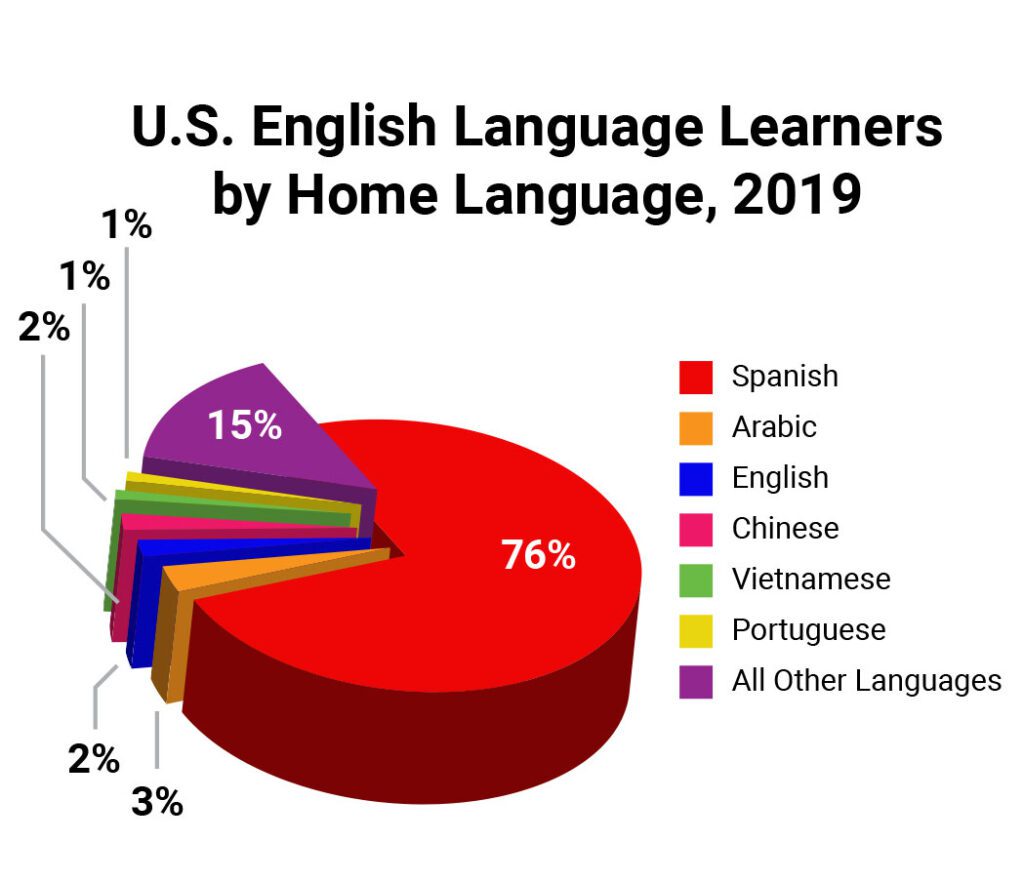

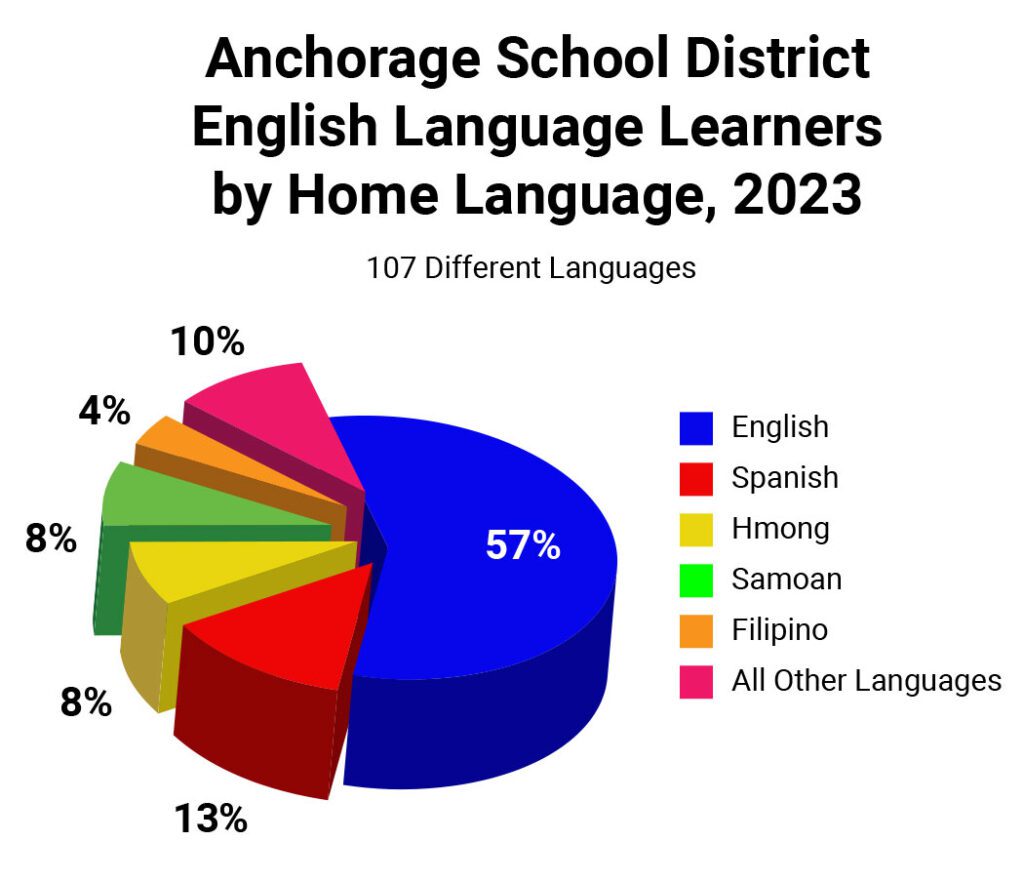

An exceptionally large number of students in Alaska are classified as ELL despite recording English as their home language. Nationally, the NCES puts the percentage of students in this category at 2.1%. In the Anchorage School District (ASD), it’s about 57%, according to data from the ASD ELL Department.

Roughly 3,800 ASD ELL students have declared English to be their home language, compared to only 690 in the entire state of Oregon. Correspondingly, Oregon’s rate of students who speak English less than “very well” is 56% higher than Alaska’s. ELL students who speak English in the home in Anchorage made up about 27% of the approximately 14,000 ELL students statewide in fiscal year 2023. How is this possible?

The higher rate of ELL students with English as their home language across Alaska seems to be driven by an unusually aggressive interpretation of the definition of the term, “English Language Learner,” under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Section 8101[20] and ESEA section 3113(b)(2), Entry and Exit Procedures.

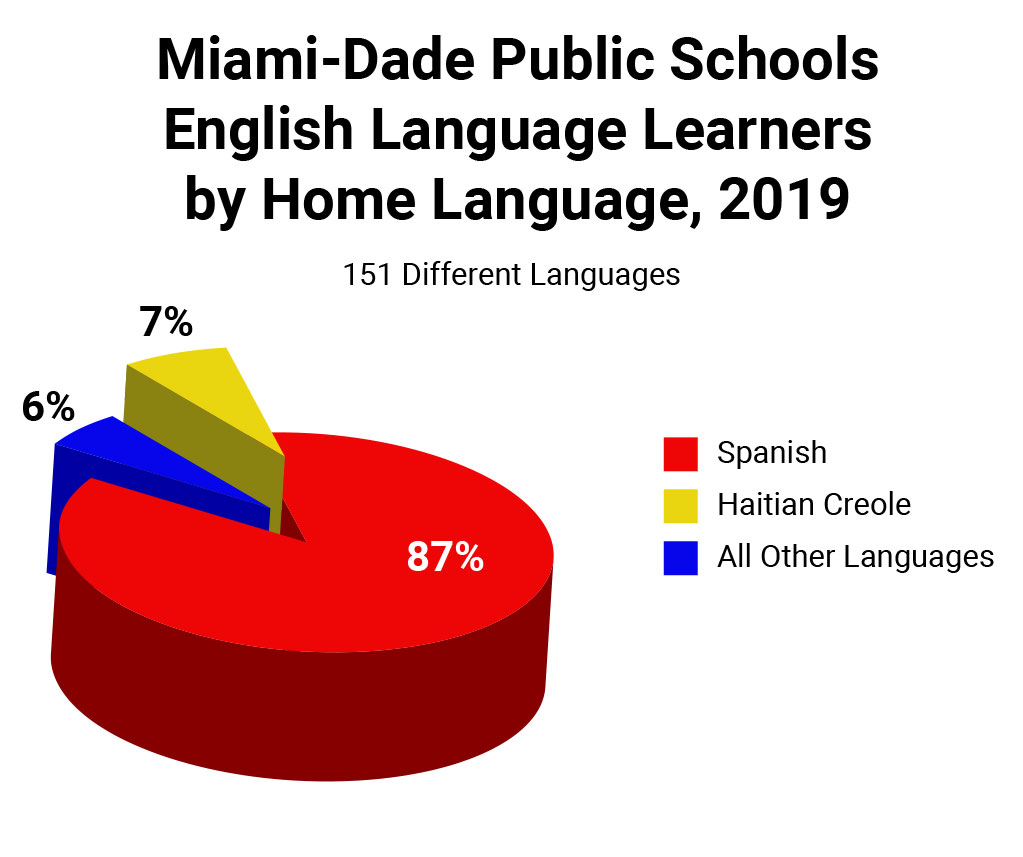

It follows that Alaska’s high ELL rate is not the result of extended exposure to and reliance on other languages, but rather an indicator of overall poor English skills for students, whom school districts then label as ELL candidates. For perspective, consider Miami-Dade in Flor- ida. Despite having fewer than half of its stu- dents identifying English as their home language (compared to 96% in Anchorage), Miami-Dade public schools’ 4th grade English reading scores on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) were about half a school year ahead of even Alaskan 4th graders too affluent to qualify for free or reduced lunch.

The references Alaskans hear frequently to the high rate of ELL students in our state seem to imply the public should lower expectations because many students are having to learn English as a second language while they tackle every other subject, too. In reality, 97.5% of Alaskan K–12 students speak English “very well” or better, according to federal government surveys. They just aren’t being taught to apply that natural experience to their studies.