By Aubrey Wursten

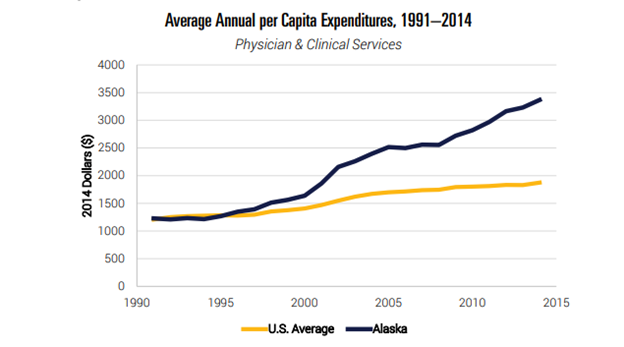

Alaska consistently suffers from the highest health care spending per capita of any state. Multiple factors contribute to this problem, but easing Alaska’s restrictions on direct primary care (DPC), or simply direct care, would provide significant relief. make entering a DPC agreement risky for doctors, which renders relatively few of them willing to do so. Even though doctors see a 40% reduction in overhead and often express increased overall satisfaction with the DPC model, they are hesitant to make the switch.

DPC functions as a health care subscription system, in which a primary care doctor charges patients a flat fee averaging $77 per month, which covers unlimited basic health care services. Essentially, it works like a membership at a 24-hour fitness club. Patients can plan routine visits for preventive care and also come in at odd hours when the unexpected arises, all without concern about unforeseen bills. Not only does this system make budgeting for health care more predictable for Alaskan patients, but it also lowers their overall costs.

Although DPC is probably the most well-known type of direct care, variations of this model work for other types of health care, including dental, surgical, and pharmaceutical. Most of these agreements do not offer the 24/7 access of DPC, and they may or may not have the membership option, but they all share the commonalities of predictable pricing and avoidance of heavy-handed third-party insurance involvement.

An Ounce of Prevention

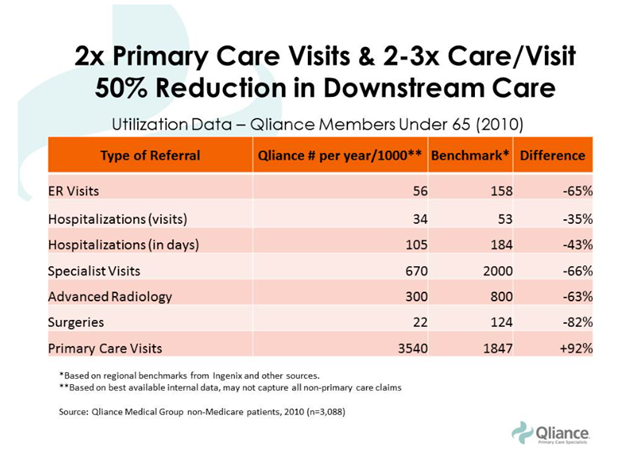

A key way to avoid paying for expensive crisis medical care is to avoid medical crises. Although some crises are inevitable, receiving routine checkups and seeking early treatment for small problems often prevents larger and more costly procedures from becoming necessary. Primary care visits reduce the need for downstream care.

Because DPC patients experience 35% lower costs in preventive care than do traditional patients, they are more likely to see a doctor and treat minor medical issues before they become major ones. DPC patients are also more likely to go to the doctor regularly for minor issues because they are free from the concern of unpredictable bills. One study found that over a two-year period, 20% of adults received a surprise medical bill from an out-of-network provider. Another study indicated that 40% “have skipped a recommended medical test or treatment in the last 12 months due to cost, and 32% were unable to fill a prescription or took less of a medication because of its cost.”

Furthermore, a visit with a DPC provider averages four times the length of a visit with a doctor in a traditional system, and the doctors tend to have fewer than half the number of patients. This is a particularly important statistic for Alaska, as it is particularly vulnerable to doctor shortages. Rural areas in general tend to have 40 physicians per 100,000 residents, compared to 53 physicians per 100,000 in urban areas, and Alaska suffers from other circumstances that exacerbate the rural-urban discrepancy. Rushed visits are a dangerous weak link in health care, with patients unable to share or receive adequate information in a typical short session with a hurried physician. This can lead to unnecessary confusion, resulting in unnecessary mistakes, which lead to unnecessary further costs.

Not surprisingly, then, a study by Society of Actuaries concluded that after adjusting for risk, DPC patients made approximately 40% fewer visits to the emergency room than did patients under traditional health care coverage models. Alaska residents make more emergency room visits per capita than the national average, but more DPC options could lower this number. Considering that the average cost of an ER visit is more than $2,000, compared to an office visit average of just $167 (and even less for a DPC patient), more DPC use would add up to significant savings for Alaskans.

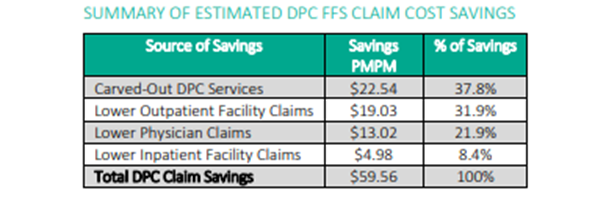

Avoiding the Middleman

Although having catastrophic insurance coverage is an important supplement to DPC, utilizing the DPC system for more routine care provides the peace of mind and predictability of an inclusive insurance plan, but at a far lower cost. In a typical health care delivery structure, 40% of primary care revenue goes to costs related to insurance companies. And in a traditional model, not only does a great deal of money go to handling even straightforward insurance claims, but patients face more uncertainty about whether or not they have received a proper bill for any service that has gone through insurance. Every extra link in the financial chain of custody provides another chance for an error, with Becker’s Hospital Review estimating the number of flawed bills at a staggering 80%. And when a patient discovers a mistake, not only is the appeals process with an insurance company lengthy and bewildering, it often comes with a fee.

Conclusion

Both patients and physicians save money under the direct primary care model, but needless legislative roadblocks in Alaska have prevented both from taking full advantage of this opportunity. Repealing useless current regulations and implementing policy recognizing the direct care model as “not a form of insurance” would be a practical step in the fight to curtail the out-of-control health care spending that have plagued Alaskans for too long.

Aubrey Wursten was APF’s Summer 2022 Policy Intern. She is currently studying at Brigham Young University-Idaho.