By Drew Godsell

A Tax Foundation report calculating and ranking states’ state and local tax burdens, ranked Alaska in 50th place with the lowest burden. This is because Alaska asks notably little of its residents when it comes to state and local taxes, largely as a result of its lack of a state income or state sales tax.

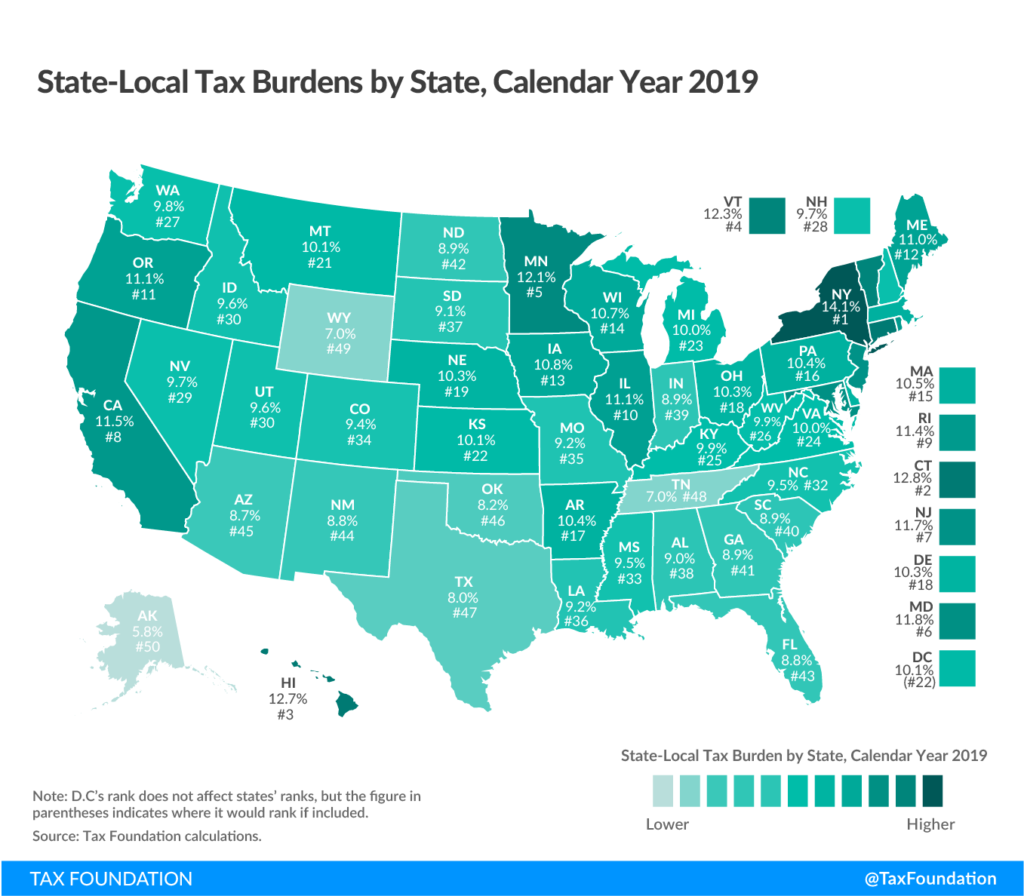

The report compares states using state-local tax burdens, calculated by dividing the total amount of state and local taxes paid by residents by the total value of goods and services produced by the state (its share of net national product). Using this calculation in 2019, Alaska’s state-local tax burden was measured at 5.8 percent. While there are property taxes and some local sales taxes in Alaska, when compared with other states, Alaska’s business tax climate has been ranked among the best.

The Tax Foundation makes an important distinction between their report and other reports that might analyze similar issues. The aim of the Tax Foundation is to compare the economic incidence of state-local taxes rather than legal incidence. In other words, the burden of a tax often falls on people who the tax is not legally imposed on. For example, raising taxes on large corporations may look like a tax on the wealthy, but since changes in costs lead to changes in behavior, the corporation may try to offset the cost of the tax by decreasing wages, laying off employees, or raising prices of consumer goods, all of which falls largely on lower-income groups. A progressive income tax may sound fair, but as a result, wealthier Alaskans may reconsider purchasing products or investing in entrepreneurial ventures, costing Alaskan jobs and innovation. A productive analysis of tax burdens, like the Tax Foundation’s, should make sure the distinction between economic and legal incidence is made and that the burden is calculated for those who truly bear it.

One way the Tax Foundation makes this distinction is by accounting for the practice of tax exporting. Tax exporting occurs when a tax is paid to a state or local government by a non-resident. Simply measuring a state’s tax collections would include taxes paid by non-residents and significantly overstate state residents’ tax burdens. In 2019, 21 percent of total state and local taxes collected in the US were paid by non-residents. Tax exporting often happens naturally but can also be set up intentionally by local and state governments. For example, large oil-producing states like Alaska do this with a severance tax, which is a tax on oil extracted and taken to be sold and used out of state. Tax exporting also occurs in the tourism industry, another big source of income for Alaska, such as in higher local taxes on hotels in popular tourist areas. Alaska is ranked the third highest in the US for exporting of tax burden.

Despite Alaska’s high tax exporting, the report notes that significant shifts in state-local tax burden are almost entirely driven by internal tax and spending changes. Alaska’s state-local tax burden fell dramatically after the completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline system in 1977 that revolutionized oil production capabilities, but this is an event Alaskans should not count on repeating.

Alaska is currently experiencing overdrawn savings accounts, meaning spending needs to be cut. While raising taxes or introducing a state income or sales tax might be tempting, these options would hurt Alaskans more than help. Not only would state income and sales taxes disincentivize labor, consumption, and entrepreneurship, but they would also be insufficient to solve the issue. Even with both a state sales tax and a progressive income tax, which would be costly to collect and enforce, a large majority of state expenditures at their current levels would remain unaccounted for. While it may be initially unpleasant, cutting the budget is Alaska’s best long-term solution.

Politicians claim the budget has been cut all it can, citing a 40 percent cut since 2013, but upon inspection, this is just not true. There is still plenty of room to improve, both in specific areas and in the process as a whole. One potential solution is zero-based budgeting, a system used by the Capital Budget, in which departments must build their budget from scratch each year, forcing annual justification of every expenditure. Alaska currently bases its Operating Budget on the previous fiscal year’s budget and builds from there, allowing wasteful or dishonest allocations of state funds to potentially go unnoticed for several years.

Alaska should treasure its last-place position when it comes to the state-local tax burden on its residents and the economic growth and freedom that come with it, especially during its recovery from the COVID-19 response. It would be easy for Alaskan politicians to claim raising taxes is responsible and just, but Alaskans must look at the facts and think about long-term consequences. Cutting spending is the only responsible way to preserve Alaska’s budgetary success, and most importantly, its economic freedom.

*******

Drew Godsell is Alaska Policy Forum’s Summer 2021 Policy Intern. He is currently studying economics and German at Hillsdale College in Michigan.