By Corey A. DeAngelis, Ph.D.

By Corey A. DeAngelis, Ph.D.

Foreword

Perhaps no societal function has been more disrupted during the 2020-and-ongoing pandemic than K-12 education. A world in which schools actually closed their doors to students was previously unimaginable to many of us. Thankfully, technology has advanced to the point that online options have been made available. But online learning has been frustrating for many parents, and while it may work to some degree for certain students, it is surely no substitute for in-person learning.

If there is anything positive that has come from the disruptions of 2020, it may be the realization by many Alaskan families that it is time to rethink how we educate students. In the sphere of education, we do not have to go back to doing things the way we did before COVID. It is time for a broad discussion of the many possibilities for educating Alaska’s children.

Here at Alaska Policy Forum, we believe in better: We envision an education system where students are continually inspired, motivated, encouraged, and challenged. That will mean different things for different children. Creating that type of environment requires choice: choice in where to get educated, how and when to get educated, in who does the educating, and even choice in “what” is taught.

Mentioning the word “choice” when talking about education will cause some readers to immediately go on the defense. But education choice does not have to be an “either-or” – previous policy debates pitted private schools against public schools. However, that’s not reality, especially in Alaska. Alternatives to residentially assigned schools do not have to always be a substitute for them. As Alaska is showing and as demonstrated in this report, alternatives can be offshoots that are still connected to the historic model, while incorporating bold, flexible possibilities.

The bottom line? Every Alaska student deserves the chance to get the education that best meets their unique needs.

Every child in every family in every community in our state deserves an exceptional education.

There is no excuse for forcing a one-size-fits-all education on our students. We have a duty to ensure the next generation and all generations following are given the opportunity to succeed and are equipped for the real world.

A common local nickname for Alaska is “The Great Land.” I think we all can agree that a great state should have a great system of education possibilities. As you will read in this report, ensuring this happens now will mean even more great things for Alaska in the future.

Bethany L. Marcum

CEO

Alaska Policy Forum

Executive Summary

It’s time for Alaska to fund students instead of institutions. Alaska could fund students directly using a taxpayer-funded education savings account program.[1] These programs allow a portion of children’s K-12 education funding to follow them to the educational provider that works best for their families. The funding can be used to cover a wide range of government-approved education expenses including private school tuition and fees, tutoring, online learning, homeschooling, pandemic pods, and microschooling.

Alaska already funds many students directly through a variety of taxpayer-funded initiatives including Alaska Pre-Elementary Grants for pre-K students, The Alaska Homeschool Allotment for K-12 students, and The Alaska Performance Scholarship for higher education students. These taxpayer-funded programs allow funding to follow students to public and private providers of educational services. This is also the case with other taxpayer-funded initiatives such as Pell Grants and the GI Bill for higher education. The money goes to the students who can then take those dollars to the public or private higher education provider of their choosing.

The state should similarly fund all K-12 students directly by enacting a statewide education savings account program. Funding students, instead of systems, would benefit families by providing them with more educational options. But how would such a program affect broader society and the economy? This report reviews the evidence on the topic and estimates the long-term economic impacts of funding Alaska students directly through a statewide education savings account program. This report also debunks some of the most common myths in the school choice debate.

Applying cautious estimates from each outcome (academic achievement, educational attainment, and crime reduction) to the 6,730 students estimated to use the program in the first year, this study finds that expanding access to education savings accounts in Alaska would be expected to provide the following long-run economic benefits:

- $194 million in economic benefits from higher lifetime earnings associated with increases in academic achievement

- $78 million in economic benefits from additional high school graduates

- $1 million from reductions in the social costs associated with crimes

Assuming a one percentage point increase in program enrollment per year, this study projects the following long-run economic benefits from the 20,190 students expected to use education savings accounts by the 2031-32 school year:

- $583 million in economic benefits from higher lifetime earnings associated with increases in academic achievement

- $235 million in economic benefits from additional high school graduates

- $3 million from reductions in the social costs associated with crimes

Keywords: private school; school choice; economics of education; charter schools

JEL Codes: I28; I20

Introduction

It’s time for Alaska to fund students instead of institutions. Alaska could fund students directly using a taxpayer-funded education savings account program. These programs allow a portion of children’s K-12 education funding to follow them to the educational provider that works best for their families. The funding can be used to cover a wide range of government-approved education expenses including private school tuition and fees, tutoring, online learning, homeschooling, pandemic pods, and microschooling.[2]

The latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicates that Alaska spends $19,017 per student[3] per year on K-12 public education, which is 28 percent higher than the national average of $14,840.[4] An education savings account funded at just half of the amount spent per student in public schools would still provide around $9,509 per student per year, which is about 30 percent higher than the average private school tuition ($7,035) in Alaska.[5] An education savings account funded at two-thirds of the amount spent per student in public schools would provide around $12,678 per student per year, which is about 80 percent higher than the average private school tuition in the state.

The flexibility of funding students directly through an education savings account is especially valuable in rural states like Alaska because families could use the costs to cover the costs of private education even if that education does not occur in a formal private school setting. This customizability is also especially important right now because of many public school systems’ failures to meaningfully adapt to the Coronavirus pandemic. According to the latest data published by Education Week in September, most of the largest public school districts in Alaska were not planning on providing full-time in-person instruction.[6] Although some teachers unions in Alaska and across the country have fought against reopening schools in person, many private businesses, including schools and daycares, have fought for the opposite.[7] A primary difference is one of incentives: one of these sectors gets your money regardless of whether they open their doors for business.

The diverse needs of individual students are also unlikely to be met by uniform top-down decisions made by government bureaucrats within a one-size-fits-all K-12 school system. In fact, a nationwide survey found that private and charter schools generally adapted better to remote learning than traditional public schools in the spring of 2020.[8] Families across the nation are scrambling for alternatives to public school systems that are not meeting their individual children’s needs.[9] In Alaska, the number of students formally enrolled in homeschooling has increased by 96 percent since last year, from 14,161 to 27,702. Many public charter schools in the state also have waiting lists because of this exodus from the traditional public school system.[10]

Alaska already funds many students directly through a variety of taxpayer-funded initiatives including Alaska Pre-Elementary Grants for pre-K students, The Alaska Homeschool Allotment for K-12 students, and The Alaska Performance Scholarship for higher education students. These taxpayer-funded programs allow funding to follow students to public and private providers of educational services. This is also the case with other taxpayer-funded initiatives such as Pell Grants and the GI Bill for higher education. The money goes to the students who can then take those dollars to the public or private higher education provider of their choosing.

Taxpayers similarly fund families directly when it comes to food stamps. The government doesn’t force low-income families to spend their food stamp dollars at residentially assigned government-run grocery stores. Instead, the funding goes to individual families who can then take that money to Carrs, Walmart, Fred Meyer, Three Bears, or just about any other provider of their choosing. We should do the same thing when it comes to K-12 education and fund students instead of institutions.

The state could fund students directly by enacting a statewide education savings account program. Funding students, instead of systems, would benefit families by providing them with more educational options. But how would such a program affect broader society and the economy? This report estimates the long-term economic impacts of funding Alaska students directly that are associated with expected improvements in academic achievement, educational attainment, and crime reduction. The report also debunks some of the most common myths in the school choice debate.

Academic Achievement

Alaska’s latest statewide school performance evaluation found that only 36 percent of students were proficient in math and 39 percent of students were proficient in English Language Arts in the 2018-19 school year.[11] The latest results from the Nation’s Report Card similarly revealed that two out of every three students in Alaska were not proficient in math and three out of every four students were not proficient in reading.[12] Alaska also ranked in the bottom five states for math and reading results on the Nation’s Report Card after controlling for differences in student background characteristics between states.[13] Increasing educational options could boost students’ academic outcomes through competitive pressures and improved matches between educators and students (Chubb & Moe; 1988; DeAngelis & Holmes Erickson, 2018; Friedman, 1955).

Seventeen random assignment evaluations have examined the effects of private school choice programs on math or reading test scores in the U.S. Similar to medical trials, random assignment evaluations of private school choice programs largely eliminate selection bias because all students in the treatment and control groups chose to enter the lottery. Given a large enough sample size and effective random assignment, we can be fairly confident that the group of students who won the lottery to attend a private school is roughly identical to the group of students who lost the lottery on all background characteristics such as income, family structure, and motivation.

The majority of the 17 random assignment studies on the topic find some evidence of positive effects of private school choice programs on students’ math or reading test scores (DeAngelis & Wolf, 2019b; EdChoice, 2020; Egalite & Wolf, 2016; Wolf & Egalite, 2019). Specifically, 10 of the 17 experimental studies detect statistically significant positive effects on math or reading test scores overall or for student subgroups (Barnard et al., 2003; Cowen, 2008; Greene, 2000; Greene, Peterson, & Du, 1999; Jin et al., 2010; Howell et al., 2002 (three locations); Rouse, 1998; Wolf et al., 2013).

Four of the 17 studies do not detect any statistically significant effects on test scores (Bettinger & Slonim, 2006; Bitler et al., 2015; Krueger & Zhu, 2004; Webber et al., 2019). However, because private school vouchers are publicly funded at substantially lower amounts than per pupil spending in public schools, statistically insignificant results imply a positive return-on-investment for taxpayers (DeAngelis, 2019a; Shakeel, Anderson, & Wolf, 2017). In the District of Columbia, for example, the average voucher amount is only about $9,531 per year,[14] whereas per pupil spending in public schools is over $30,000 each year.[15] In other words, the latest evaluation of the D.C. voucher program found that the private schools achieved the same math and reading results as the public schools at around a third of the cost (Webber et al., 2019).[16] Only two of the 17 studies, both of the highly regulated Louisiana Scholarship Program, find negative effects on math or reading test scores (Abdulkadiroğlu, Pathak, & Walters, 2018; Mills & Wolf, 2019). One study found mixed results (Lamarche, 2008).

Shakeel, Anderson, and Wolf (2016) conducted a meta-analysis including 15 of these experimental evaluations and concluded that private school choice programs increased or had no effect on academic achievement in the United States. The overall average math and reading effect sizes across all studies, calculated by Shakeel, Anderson, and Wolf (2016), ranged from zero percent of a standard deviation to seven percent of a standard deviation.

Zimmer et al. (2019) recently summarized the random assignment evaluations of public charter schools in the U.S. and similarly concluded that “lottery-based analyses have generally shown strong positive effects on student achievement of charter school admission and enrollment.” Betts and Tang (2019) performed a meta-analysis of 38 rigorous studies and found that public charter schools increased reading achievement by 2 percent of a standard deviation and increased math achievement by 3.3 percent of a standard deviation overall.

Hoxby (2004) conducted a nationwide analysis of 99 percent of elementary students who attended public charter schools in the United States. This analysis revealed that the students in public charter schools were 5.2 percent more likely to reach proficiency in reading and 3.2 percent more likely to reach proficiency in math than their peers in nearby traditional public schools with similar racial compositions. These positive results were especially pronounced for public charter schools in Alaska. Hoxby (2004) found that students in public charter schools were about 20 percent more likely to reach proficiency in reading and math than their peers in the matched traditional public schools. A more recent descriptive analysis of statewide assessment data from 2019 similarly found that Alaska’s public charter schools generally outperformed traditional public schools in the state. Alaska’s public charter schools achieved a 15-percentage point higher rate of English Language Arts proficiency and a 12-percentage point higher rate of math proficiency than the average for all public schools in the state (Montalbano, 2020).

In order to link the potential achievement effects of private school choice in Alaska to changes in lifetime earnings, I combine the academic achievement literature with findings from Stanford University economist Eric Hanushek. Hanushek (2011) observed that a one standard deviation increase in student achievement is associated with a 13 percent increase in lifetime earnings.[17] Following the methodology from previous evaluations (e.g., DeAngelis, 2018; DeAngelis, 2020a; DeAngelis, 2020b; DeAngelis, 2020c; DeAngelis, 2020d; DeAngelis et al., 2019; DeAngelis & DeGrow, 2018; DeAngelis & Flanders, 2018; Wolf et al., 2014), it is possible to forecast the potential effects of private school choice programs on lifetime earnings.

Using Betts and Tang’s (2019) more cautious estimate of school choice’s effects on student achievement (a 2.0 percent of a standard deviation positive effect on reading scores), because 70 percent of learning is retained from one year to the next (Hanushek, 2011), the possible effects of private school choice on lifetime earnings in Alaska can be forecast using the following two equations:

Avg Lifetime Earnings * [1 + (0.02) * (0.13/SD) * (0.70)]13 = Expected Lifetime Earnings (1)

Expected Lifetime Earnings – Avg Lifetime Earnings = Gain in Lifetime Earnings (2)

To calculate the net present value of lifetime earnings in 2020 dollars, I assume that each student will work for 46 years, or from the age of 25 to the age of 70. Using a discount rate of 3 percent, and the median wage in Alaska in 2019 ($48,540)[18] from the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, the net present value of median lifetime earnings in Alaska is $1,207,834. This number is the best approximation available for the expected lifetime earnings of individuals educated in traditional public schools in the state since the majority of Alaska students attend traditional public schools.[19]

Plugging this information into equation (1) produces an expected lifetime earnings of $1,236,725 for students attending private schools for their entire K-12 education. Plugging this information into equation (2) produces an expected gain in lifetime earnings of $28,892 for each child using a private school choice program in the state.

$1,207,834 * [1 + (0.02) * (0.13/SD) * (0.70)]13 = $1,236,725 (1)

$1,236,725 – $1,207,834 = $28,892 (2)

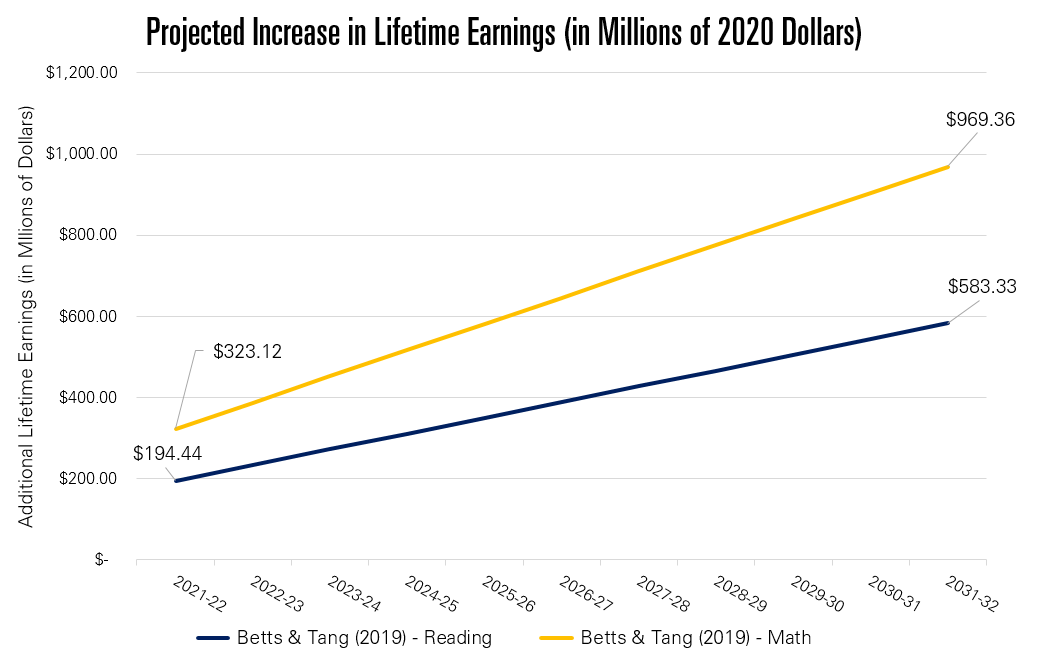

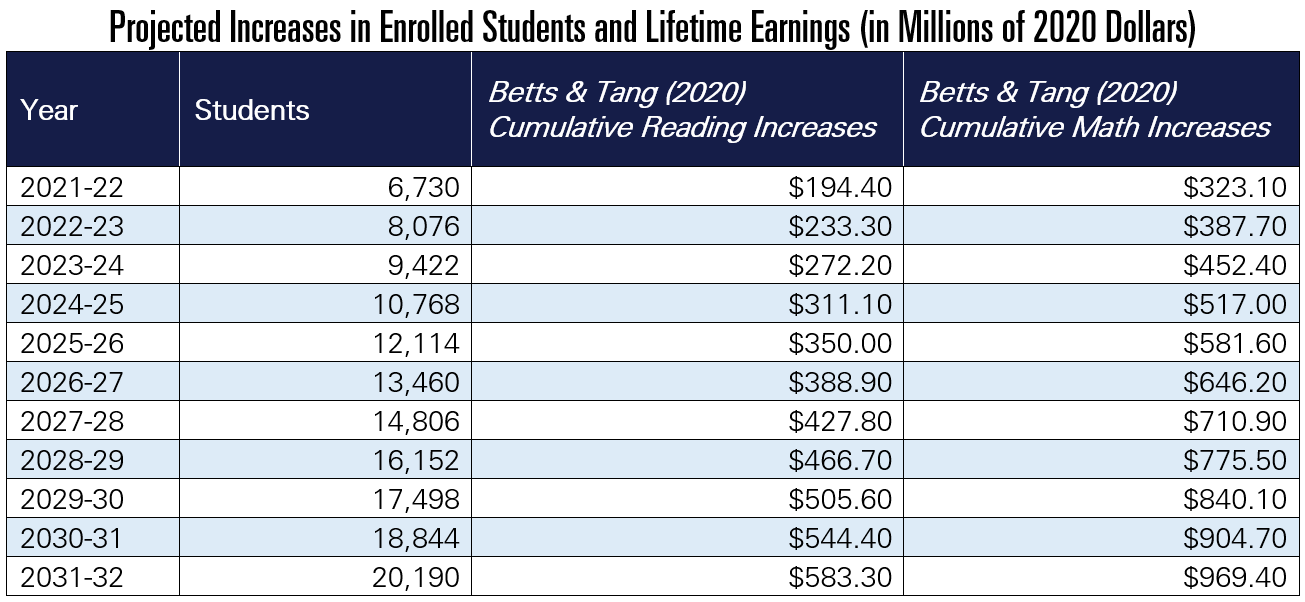

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 134,600 students were projected to enroll in public K-12 schools in Alaska in the 2021-22 school year.[20] Assuming 5 percent of that population of students used a statewide education savings account program, that would be 6,730 students benefiting from additional educational options.[21] An additional $28,892 in lifetime earnings for each student accessing the program would amount to a cumulative economic benefit of about $194 million (6,730 x $28,892). If an additional one percent of the school-aged population takes advantage of the education savings account program each year, then 13,460 students would benefit from the program by 2026 and 20,190 students would benefit from the program by 2031. The additional academic achievement experienced by these students is estimated to lead to an additional $583 million in lifetime earnings for students using the program by 2031 (20,190 x $28,892). These projected results can be found in Table 1 and Figure 1. Results are also reported for models based on the larger positive results for math test scores reported by Betts and Tang (2019) (Column 4 in Table 1). These estimates are likely cautious based on the much larger positive results reported by the two Alaska-based studies (Hoxby 2004; Montalbano 2020).

Table 1

Source: Author’s calculations

Figure 1

Source: Author’s calculations

The estimates of economic benefits reported in this section should be assessed with caution because effects on standardized test scores may not always be strong proxies for effects on lifetime earnings. Although studies such as Hanushek (2011) and Chetty, Friedman, Rockoff (2014) suggest that higher standardized test scores tend to be associated with higher earnings, two reviews of the school choice literature suggest that schools’ effects on standardized test scores often do not successfully predict their effects on long-term outcomes such as educational attainment (DeAngelis, 2019a; Wolf, Hitt, & McShane, 2018).

Educational Attainment

Educational attainment includes high school graduation, college enrollment, college persistence, and college completion. The evidence linking private school choice programs to these educational attainment outcomes leans positive. Foreman (2017) reviewed this evidence and found that all five studies on the subject indicated statistically significant positive effects of private school choice programs on at least one educational attainment outcome overall or for subgroups of students. EdChoice (2020) similarly found that four out of six rigorous studies on the subject indicated attainment benefits of private school choice programs in the U.S. overall or for student subgroups. None of the reviewed studies found negative effects of private school choice programs on attainment outcomes overall or for student subgroups.

Most recently, DeAngelis and Wolf (2019b) reviewed the literature on private school choice and educational attainment and found eight rigorous evaluations on the subject. Six of the eight evaluations found statistically significant positive effects of private school choice programs on at least one measure of educational attainment overall or for student subgroups (Cheng, Chingos, & Peterson, 2019; Chingos, Monarrez, & Kuehn, 2019; Chingos & Peterson, 2015; Cowen et al., 2013; Wolf et al., 2013; Wolf, Witte, & Kisida, 2019). For example, Wolf et al. (2013) found that winning a lottery to use a voucher to attend a private school in D.C. increased the likelihood of graduating from high school by 21 percentage points. Cowen et al. (2013) found that students using the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program were about 4 percentage points more likely to graduate from high school than their carefully matched peers in public schools. The two remaining evaluations did not find any statistically significant effects of school choice on educational attainment overall in Louisiana (Holmes Erickson, Mills, & Wolf, 2019) or the District of Columbia (Chingos, 2018).

Data from the National Center for Education Statistics show that the four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate for public high schools in Alaska was only 78.5 percent in the 2017-18 school year. Alaska’s public high school graduation rate was 6.8 percentage points lower than the national average of 85.3 percent. In fact, Alaska’s public high school graduation rate was lower than every other state except for New Mexico and the District of Columbia. Alaska’s high school graduation rates were even lower for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. For example, the latest data indicate that only 72 percent of economically disadvantaged students and 57 percent of students with disabilities graduated from high school.[22]

It is possible to forecast expected economic benefits associated with access to private school choice in Alaska by linking these estimates to information about the economic value of additional high school graduates. High school graduates produce economic benefits to society through higher productivity, additional tax revenues from higher earnings, and reductions in social costs associated with tax-funded healthcare, crime, and welfare. Vining and Weimer (2019) estimated that the net present value of an additional high school graduate was about $300,000. Levin (2009) estimated the net present value of economic benefits associated with an additional high school graduate was $209,100 in 2004 dollars. According to the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, Levin’s (2009) estimate for the economic value of an additional high school graduate is equal to about $291,262 in 2020 dollars after adjusting for inflation. This analysis relies on the more cautious estimate reported by Levin (2009).

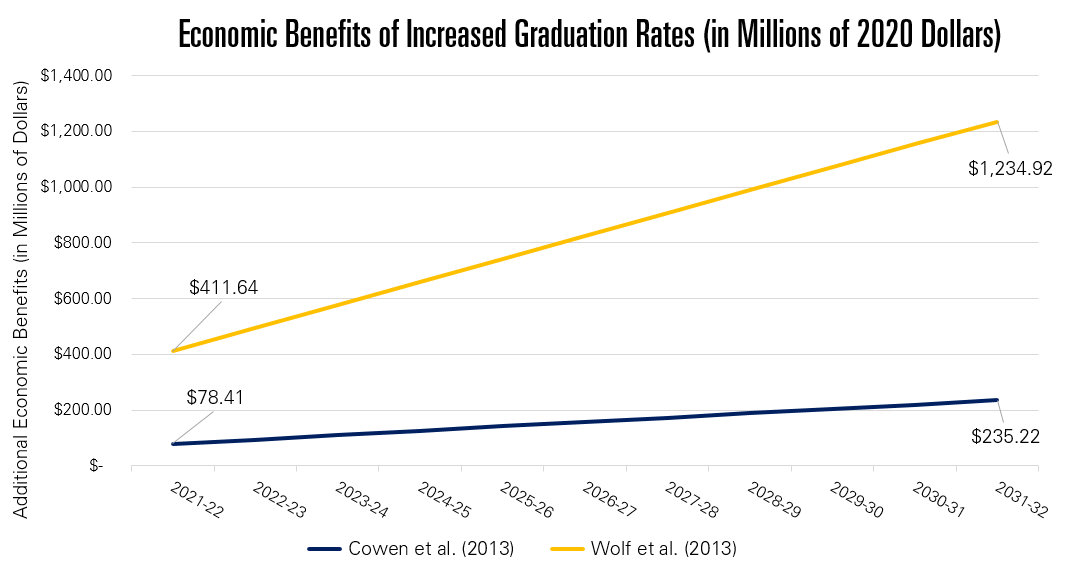

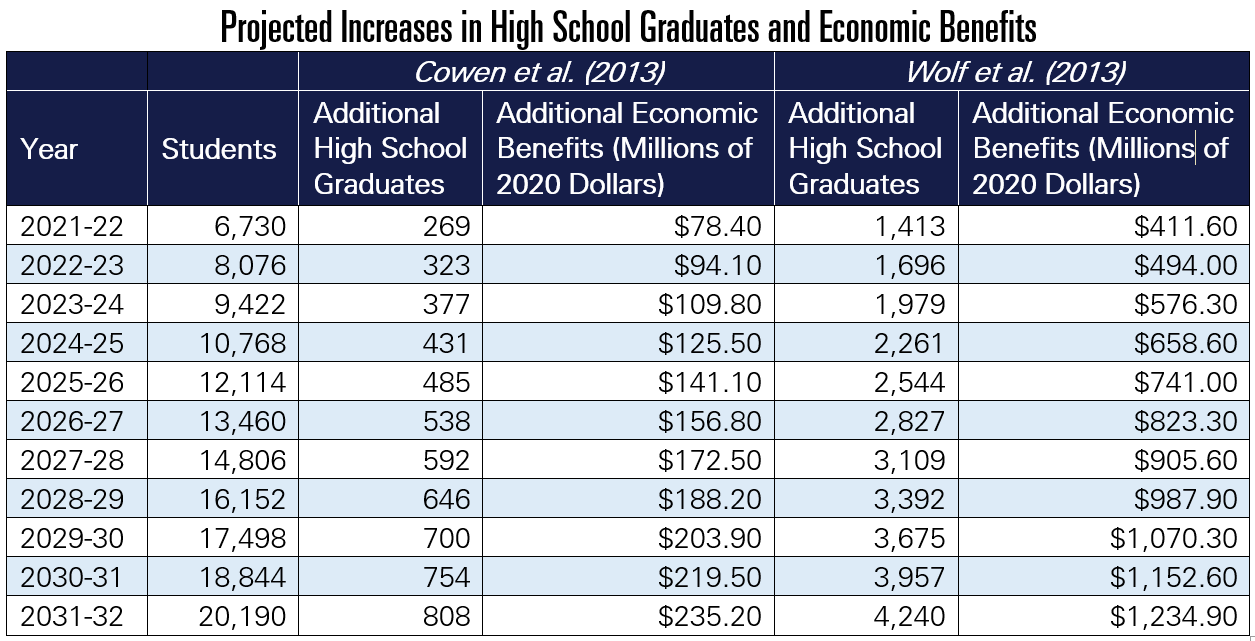

This study’s preferred model relies on the positive results found by Cowen et al. (2013) to provide cautious estimates of economic impacts. These results suggest private school choice could increase high school graduation rates by at least four percentage points in Alaska. The estimates from Levin (2009) and Cowen et al. (2013) can be combined with the expected number of students using private school choice programs in Alaska each year to forecast economic benefits. Equations (3) and (4) show the forecasted economic benefits accrued by the 6,730 students that would benefit from the program in the 2021-22 school year.

6,730 students * 0.04 = 269 additional graduates (3)

269 additional graduates * $291,262 = $78.3 million in economic benefits (4)

As shown in equation (3), a four-percentage point increase in high school graduation rates would be expected to produce 269 additional high school graduates. Equation (4) estimates that a 269-student increase in high school graduates would be expected to translate to about $78 million in additional economic benefits over their lifetimes. Increased graduation rates would be expected to produce 808 additional graduates by 2031, which would be expected to translate to around $235 million in additional economic benefits over their lifetimes (Table 2 and Figure 2). Results are also reported for a model based on the larger positive result found by Wolf et al. (2013)’s random assignment evaluation of the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program (Columns 5 and 6 in Table 2).

Table 2

Source: Author’s calculations

Figure 2

Source: Author’s calculations

Crime Reduction

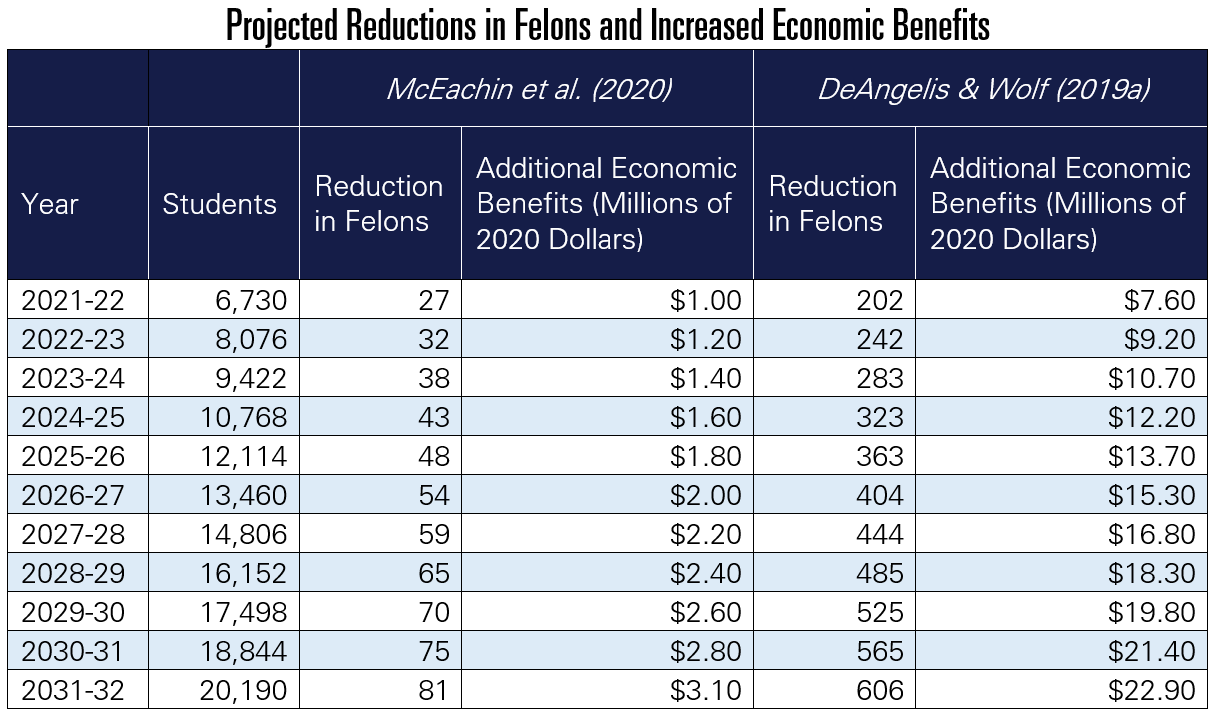

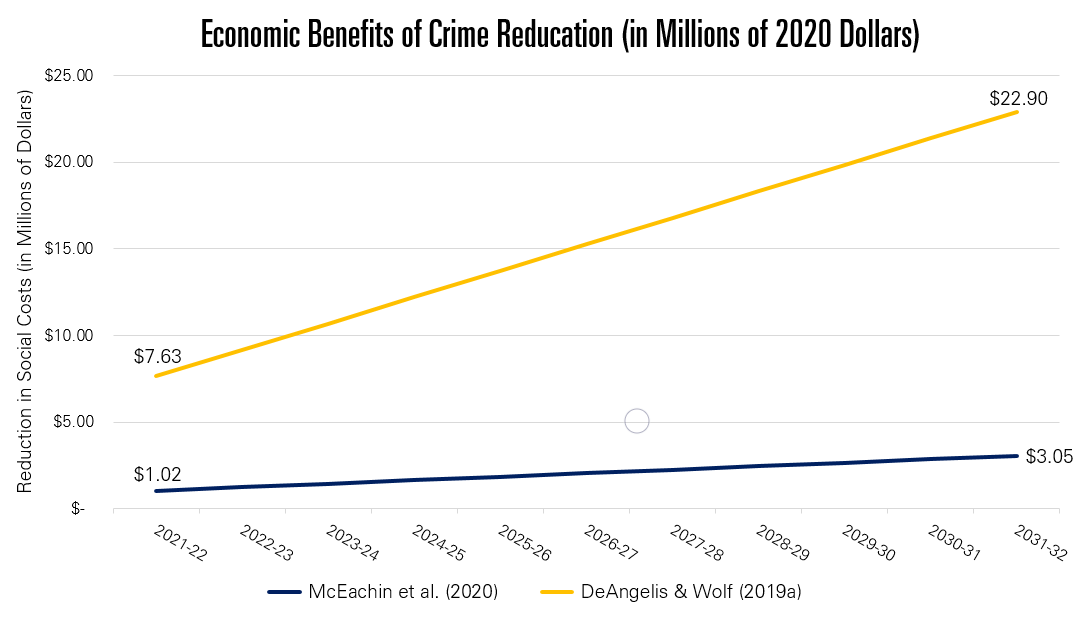

School choice programs could reduce crime through competitive pressures to improve behavioral outcomes, improvements in discipline policies, and by providing access to cultures and peer groups that discourage risky behaviors (DeAngelis & Wolf, 2019a). Six rigorous peer-reviewed studies link access to school choice to crime outcomes in the United States. Each of the six studies finds statistically significant positive effects on crime reduction overall or for subgroups of students (DeAngelis & Wolf, 2019a; DeAngelis & Wolf, 2020; Deming, 2011; Dills & Hernández-Julián, 2011; Dobbie & Fryer, 2015; McEachin et al., 2020).[23] The two random assignment studies on the topic both find that winning a school choice lottery largely reduces incarceration rates for male students (Deming, 2011; Dobbie & Fryer, 2015). For example, Dobbie and Fryer (2015) found that winning a lottery to attend a public charter school in New York City reduced incarceration for male students by 4.4 percentage points. Deming (2011) found that winning a lottery to attend a public school of choice reduced criminal activity by about 50 percent for high-risk male students. DeAngelis and Wolf (2019a) similarly found that students who used the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program for at least four years were around 3 percentage points less likely to be found guilty of a felony than their carefully matched peers in nearby public schools.

McEachin et al. (2020) found that North Carolina students entering public charter schools in 9th grade were 0.9 percentage points less likely to commit any crimes, 0.7 percentage points less likely to be convicted of a misdemeanor, and 0.4 percentage points less likely to be convicted of a felony than their matched peers in traditional public schools. McEachin et al. (2020) also found that students who stayed in a charter school in 9th grade relative to those who switched back to traditional public schools in the same year were marginally less likely to be convicted of any crimes. McEachin et al. (2020) also found evidence suggesting access to charter schools improved other behavioral outcomes by reducing chronic absenteeism and suspensions.

The costs of crimes can be divided into four categories: direct economic losses suffered by victims, indirect losses suffered by victims, criminal justice system costs, and negative effects on job prospects and productivity for criminals (McCollister, French, & Fang, 2010). Based on the average social costs of crimes estimated by McCollister, French, and Fang (2010) and the average social cost of a felony estimated by Flanders and DeAngelis (2018), it is possible to forecast the economic impact of private school choice in Alaska. Using the sample of crimes reported in a longitudinal evaluation of the Milwaukee voucher program, Flanders and DeAngelis (2018) estimated the average cost of a felony to be $35,950 in 2017 dollars, or about $37,800 in 2020 dollars.

Using the more cautious estimate of a 0.4-percentage point reduction in felonies found by McEachin et al. (2020), and the number of students expected to use education savings accounts in Alaska the first year, equations (5) and (6) can be used to forecast economic benefits:

6,730 students * -0.004 = 27 fewer felons (5)

27 fewer felons * $37,800 = $1 million in economic benefits (6)

If we observe similar crime-reducing benefits in Alaska, access to education savings accounts could reduce crime by 27 felons for the population of students expected to use the statewide program in the first year. This reduction in felons would be expected to produce about $1 million in economic benefits by reducing the social costs associated with crimes. Access to the program would be expected to lead to 81 fewer felons by 2031, which would lead to around $3.1 million in social benefits associated with reductions in crime (Table 3 and Figure 3). Results are also reported for a model based on the larger positive result found by DeAngelis and Wolf (2019a)’s evaluation of a private school choice program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Columns 5 and 6 in Table 3).

Table 3

Source: Author’s calculations

Figure 3

Source: Author’s calculations

Social Benefits

This report likely underestimates the true economic benefits of school choice initiatives because the above calculations do not capture social benefits associated with improved civic outcomes, satisfaction, and equity. Allowing education dollars to follow children to the educational environment that works best for them has other benefits that are not easily quantifiable in terms of dollars and cents. For example, six reviews have summarized the rigorous literature linking school choice to civic outcomes such as political knowledge, political participation, voluntarism, civic engagement, charitable activity, and tolerance of others. All six of these reviews find that access to private school choice generally improves civic outcomes (DeAngelis, 2017; DeAngelis & Wolf, 2019b; EdChoice, 2020; Greene, 2005; Wolf, 2007; Wolf, 2020).

Wolf (2007) reviewed 21 studies on the topic that reported 59 different findings. Wolf (2007) reported that a majority (33 of 59) of the findings indicated statistically significant positive effects of access to private and charter schools, whereas only three of the findings revealed the opposite. More recently, Wolf (2020) updated his initial review and found similar positive results. He found 34 studies reporting a total of 86 findings on the relationship between access to private schools and civic outcomes. Wolf (2020) found that a majority (50 of 86) of the findings demonstrated a statistically significant advantage for private schools relative to public schools. Only three of the 86 findings indicated a statistically significant advantage for traditional public schools, whereas the remaining 33 results indicated no statistically significant differences between sectors.

Limiting search results to rigorous evaluations of private school choice programs, DeAngelis (2017) performed a systematic review of the literature and found 11 evaluations on the topic. A majority of those evaluations found statistically significant positive effects of private school choice programs on civic outcomes, whereas none of the evaluations found statistically significant negative effects overall. DeAngelis and Wolf (2019) updated this review and found that seven out of 12 studies on the topic detected statistically significant positive effects of private school choice on civic outcomes overall. None of the 12 studies detected statistically significant negative effects overall. EdChoice (2020) reviewed 11 studies on the topic and found that six detected statistically significant positive effects. Again, none of the studies reported negative effects.

Families choose specific educational alternatives for their children for a host of reasons. Parents consistently rank safety at near the top of their priority list when seeking educational options (Bedrick & Burke, 2018; Catt & Rhinesmith, 2017; Holmes Erickson, 2017; Kelly & Scafidi, 2013). DeAngelis and Wolf (2019) summarized the evidence linking private school choice to safety and found six studies on the topic. Each of the six studies reported statistically significant positive effects on safety as reported by students, parents, or principals. More recently, Schwalbach and DeAngelis (2020) reviewed the evidence and found 11 rigorous studies on the topic. Each of the 11 studies found private school safety advantages as reported by parents, students, or faculty (DeAngelis & Lueken, 2020; Dyehouse et al., 2020; Fan, Williams, & Corkin, 2011; Farina, 2019; Howell & Peterson, 2006; Lleras, 2008; Shakeel & DeAngelis, 2018; Waasdorp et al., 2018; Webber et al., 2019; Witte et al., 2008; Wolf et al., 2010).

Families are overwhelmingly satisfied when they have access to private school choice. Rhinesmith (2017) found 19 studies linking private school choice to parental satisfaction, and each of the evaluations revealed positive effects. EdChoice (2020) more recently reviewed this body of evidence and found that 29 of 30 studies on the topic revealed a positive relationship between private school choice and parental satisfaction. Eight random assignment studies each find that winning a lottery to use a private school choice program improved satisfaction as reported by students or their parents (Greene, 2001; Howell & Peterson, 2002 (four locations); Kisida & Wolf, 2015; Peterson & Campbell, 2001; Webber et al., 2019). Another study using a nationally representative sample from the U.S. found that “public charter schools and private schools outperform traditional public schools on six measures of parent and student satisfaction” after controlling for several differences in student and family background characteristics between sectors (DeAngelis, 2019b).

Taxpayer Savings

It is also possible that universal education savings accounts could save taxpayer dollars since they are typically funded at an amount below what would have been spent on the student in traditional public schools. EdChoice (2020) summarized the evidence and found that 49 of 55 studies on the topic indicate that private school choice programs save taxpayer money (e.g. Aud, 2007; Lueken, 2018; Trivitt & DeAngelis, 2020; Wolf & McShane, 2013).

The latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that Alaska spends $19,017 per student[24] per year on K-12 public education, which is 28 percent higher than the national average of $14,840.[25] An education savings account funded at just half of the amount spent per student in public schools would still provide around $9,509 per student per year, which is about 30 percent higher than the average private school tuition ($7,035) in Alaska.[26] An education savings account funded at two-thirds of the amount spent per student in public schools would provide around $12,678 per student per year, which is about 80 percent higher than the average private school tuition in the state.

If all K-12 public education funding were based on student enrollment in Alaska, and if 10 percent[27] of students using an education savings account program would pay for private education out-of-pocket, a universal education savings account funded at just half ($9,509) of the public school spending amount ($19,017) would likely save taxpayer money each year. Each student switching from public schools would save taxpayers $9,509 ($19,017 – $9,509) whereas each student who would have accessed private education anyway would cost taxpayers $9,509. If 6,730 students used the program in the first year, and 10 percent of those families would have paid for private education absent the program, the state would save over $51 million in one year [($19,017 * 6,730 * 0.9) – ($9,509 * 6,730)].

The state would be expected to save taxpayer money if less than 50 percent of students using the program would pay for private education without financial assistance [1 – ($9,509/$19,017)]. However, if traditional public schools in Alaska keep a significant portion of dollars for students who are no longer enrolled, the net fiscal impact of such an education savings account is unclear and warrants further analysis.

School Choice Myth-Busting

A lot of myths in the school choice debate crumble under the slightest bit of scrutiny (DeAngelis & McCluskey, 2020). The most common myth by far is the claim that “school choice siphons money away from public schools.” School choice does not “siphon money away from public schools.” The reality is that public schools siphon money away from families. School choice initiatives simply return that money to the hands of the people that it’s meant for – the students and their families. Families still have the opportunity to take those dollars back to the same residentially assigned public school if they would like. Imagine if someone claimed that allowing families to choose their grocery store “siphons money away from Safeway” or allowing students to take their Pell Grants to private universities “siphons money away from state-run community colleges.” Everyone would understand those claims would be absolutely ridiculous because the funding doesn’t belong to any particular institution. K-12 education funding similarly doesn’t belong to any particular institution – public or private. Education funding is meant for educating children – not for propping up and protecting a government monopoly.

The argument that “school choice siphons away money from public schools” also begs the question: why would giving families a choice result in less funding for public schools? This claim is an admission that the defenders of the public school monopoly understand that families will choose alternatives when given a choice (Lueken & Scafidi, 2020). If the public schools were meeting the needs of families, then the opponents of school choice would have nothing to fear. But the reality is that fewer than half of the families with students in traditional public schools report that they would keep their children in them if given meaningful options to educate their children elsewhere (e.g. DiPerna, Catt, & Shaw, 2020; Schultz, 2020). In this sense, public schools defund themselves when they fail to meet the diverse needs of individual families. No wonder opponents of educational freedom fight so hard to prevent families from having an exit option.

A related myth is that school choice would “harm the children left behind in public schools.” But it is also possible that the children who remain in residentially assigned public schools will be better off for two reasons (1) residentially assigned public schools end up with more money per student if they are not funded solely based on enrollment counts, and (2) school choice competition incentivizes public schools to improve. A large body of evidence suggests competitive pressures from private school choice leads to improvements in outcomes for children who remain in the traditional public school system (Ladner, 2020). This improvement is likely because the traditional public schools start to change their approaches to cater to the needs of families to avoid losing any of the funding associated with students who choose to leave.

As EdChoice (2020) has documented, 26 of 28 studies on the topic find statistically significant positive effects of school choice competition on outcomes in public schools (e.g. Chakrabarti, 2013; Egalite & Mills, 2019; Figlio, Hart, & Karbownik, 2020; Hoxby, 2000; Rouse et al., 2013). Egalite (2013) similarly found that 20 of 21 studies revealed positive effects of private school competition. More recently, the most comprehensive meta-analysis of the evidence on this topic found statistically significant positive effects on public schools overall (Jabbar et al., 2019). Put differently, private school choice is a rising tide that lifts all boats. As a result of competitive pressures, students do not even have to participate in school choice programs to benefit from them. This body of evidence is generally positive. But the right of low-income families to choose the educational setting that works best for their own children should not hinge on the competitive response of a government-run institution. And besides, these kinds of arguments aren’t used to prevent advantaged families from choosing the school that works best for their children, and they shouldn’t be used to take similar opportunities from less advantaged families either.

Opponents of educational freedom argue that school choice leads to inequities. But trapping disadvantaged students in public schools that have been failing them for decades is what truly exacerbates inequities. Funding students directly leads to more equity by allowing more children to have educational opportunities. Advantaged families already have school choice since they are more likely to have the resources to pay for private education out of pocket or to purchase a residence that happens to be assigned to the best traditional public school in the area (Cheng, 2020). Inequities are inherent in the traditional public school system because of artificial barriers to accessing the best schools created by residential assignment and inequitable funding. In fact, some parents have been fined or even thrown in jail for lying about their addresses to get their children into better public schools (Lowrey, 2019). Advantaged families can even buy their way into some top public school districts that charge tuition for students living outside of their attendance zones (Barnard, 2019). In this way, many traditional public schools are not “public” in any meaningful sense of the word. They are not open to the public because they discriminate on the basis of ZIP code. They are not true “public goods” since they are excludable and rivalrous (DeAngelis, 2018).

Allowing the money to follow the child to the best educational setting leads to more equity because it allows less-advantaged families to access alternatives (Wolf, 2018). Although universal school choice would lead to more equity as well, the vast majority of existing private school choice programs are targeted to less-advantaged families by income, special need, or the quality of their child’s residentially assigned public school.[28] Some studies also suggest that out of the relatively disadvantaged group of eligible families, the less-advantaged families are generally more likely to apply for access to school choice programs, perhaps because their children are less likely to be adequately served by their residentially assigned public schools (Anderson & Wolf, 2017; Hart, 2014; Figlio, Hart, & Metzger, 2010).[29]

Constitutionality

Another common myth is that “school choice is unconstitutional” because it supposedly violates the Establishment Clause of the 1st Amendment of the U.S. Constitution since taxpayer dollars can be used at religious schools. But private school choice programs do not violate the Establishment Clause for the same reason Pell Grants and the GI Bill for higher education do not violate the establishment clause: the funding goes to students who can choose to take those dollars to religious or nonreligious public or private schools. The same goes for the federal Head Start program and other taxpayer-funded pre-K programs.

Food stamps are used to purchase food from private businesses that may or may not support religious entities – and Medicaid dollars can be used at hospitals with religious affiliations – without violating the Establishment Clause. Social Security dollars can similarly be used at private religious institutions, including K-12 schools and even places of worship, without violating the Establishment Clause. Allowing families to choose to use their children’s education dollars at religious or nonreligious public or private schools clearly does not violate the Establishment Clause because families and students – not schools – are the primary beneficiaries of each of these programs (Keller, 2020).

The U.S. Supreme Court has also acknowledged the fact that private school choice programs are constitutional. Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002) ruled in a 5-4 decision that a taxpayer-funded private school voucher program in Ohio did not violate the Establishment Clause even though the funding could be used at private religious schools.[30] Mueller v. Allen (1983) similarly ruled in a 5-4 decision that a state tax deduction granted to taxpaying parents for public and private school-related expenses in Minnesota did not violate the Establishment Clause.[31] A related case, Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer (2017) ruled in a 7-2 decision that the exclusion of churches from an otherwise neutral and secular aid program for schools violated the Free Exercise Clause of the 1st Amendment.[32] Most recently, Espinoza v. Montana (2020) ruled in a 5-4 decision that the Montana Constitution’s “no aid” provision ending a private school choice program discriminated against religious schools and families and unconstitutionally violated the Free Exercise Clause.[33]

Thirty-seven state constitutions, including Alaska’s, include Blaine Amendments that were created with the intent to prevent taxpayer dollars from being used at Catholic schools so that the money could be kept in “public” schools that were largely Protestant in orientation (Glenn, 1988; Green, 2003; Keller, 2020). The latest decision in Espinoza v. Montana (2020) dealt a mortal blow to these discriminatory Blaine Amendments that were rooted in anti-Catholic animus. As Keller (2020, pg. 63) explained, “under Espinoza, Blaine Amendments are no longer a barrier to educational choice programs that empower parents to choose religious educational options alongside nonreligious options.” Keller (2020, pg. 63) also pointed out that “even before Espinoza, most state courts had concluded that it is the students themselves – not religious schools – who are the true beneficiaries of educational choice programs.”

Four decades before the Espinoza decision, Alaska’s Supreme Court ruled in Sheldon Jackson College v. State (1979) that the state’s Blaine Amendment prohibited students from using post-secondary tuition grants to cover the costs of attending private colleges. Alaska’s Blaine Amendment reads “No money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.” Funding students directly through education savings accounts or other educational choice programs did not legitimately violate Alaska’s Blaine Amendment, even before Espinoza, because students are the primary beneficiaries of the funding rather than schools. Alaska’s Blaine Amendment states private educational institutions cannot receive a “direct” taxpayer funding benefit. Notice that the state’s Blaine Amendment does not say anything about private educational institutions receiving “indirect” benefits. This is an important distinction that was deliberated during the Alaska Constitutional Convention in 1956. The proposed amendment at that time to add the word “indirect” to the Blaine Amendment was soundly defeated 34 to 19 with two absent.[34] Although private educational institutions may indirectly benefit from allowing families to choose public or private schools, families and students are the direct beneficiaries of these programs.

This might be why Alaska already has several other taxpayer-funded programs that can be used by students and families to pay for private educational services. The Alaska Performance Scholarship, for example, is a taxpayer-funded program that allows students to direct “public funds” to the participating religious or nonreligious public or private educational institution of their choosing.[35] The Alaska Pre-Elementary Grants program similarly allows state funding to follow children to some public or private providers of educational services.[36] Alaska also has about 30 programs that allow families to use state funds for homeschooling.[37] The Alaska Homeschool Allotment allows families to use about $2,000 of taxpayer funding to cover homeschooling costs including books, materials, online learning, tutors, and other educational activities.[38] The bottom line: Alaska’s Blaine Amendment is clearly not an insurmountable barrier to funding students directly through a statewide education savings account program.

Conclusion

This report estimates that funding all students directly through a statewide education savings account program would have substantial economic benefits. For the cohort of students expected to use the program in the first year, the most cautious model suggests that such a program would provide about $194 million in economic benefits from higher lifetime earnings associated with increases in academic achievement. This report also estimates that, over the lifetimes of the first cohort of students, such a program would provide at least $78 million in economic benefits associated with additional high school graduates and $1 million in economic benefits from crime reduction.

Funding students directly is likely to produce substantial social and economic benefits. But the case for educational freedom goes beyond dollars and cents. The main problem with K-12 education is the massive power imbalance between the public school system and families. Traditional public school districts hold substantial monopoly power because of residential assignment and compulsory funding through taxes. Families are essentially powerless in this relationship because a particular educational institution gets to retain substantial amounts of their children’s education dollars regardless of their levels of satisfaction or their preferences.

This uneven power dynamic is becoming clearer to more and more families this year. It’s one thing for a public school system to get your children’s education dollars despite failing to meet their needs year after year. It’s another conversation altogether for that same institution to get your children’s education dollars when its doors aren’t even open for business. Think of it this way: if a grocery store doesn’t reopen, families can take their money elsewhere. If a school doesn’t reopen, then families should similarly be able to take their children’s education dollars elsewhere. As a matter of fact, families should be able to take their children’s education dollars elsewhere regardless of their residentially assigned school’s reopening decision. After all, education funding is supposed to be meant for educating children – not for protecting a particular institution.

Families are getting a bad deal and they know it. In fact, a nationwide survey recently found that support for school choice initiatives surged by 10 percentage points in 2020, from 67 percent in April to 77 percent in August (Schultz, 2020). Another nationwide survey recently found that support for education savings accounts increased by four percentage points over the past year, from 77 percent in 2019 to 81 percent in 2020 (DiPerna, Catt, & Shaw, 2020). The same national survey found that support for private school voucher programs jumped by 10 percentage points over the past year, from 63 percent in 2019 to 73 percent in 2020 (DiPerna, Catt, & Shaw, 2020). Families are realizing that there aren’t any good reasons to fund institutions when we can fund students directly instead. We already do this with so many other taxpayer-funded initiatives including Pell Grants for higher education and state-funded Pre-K programs. K-12 education should catch up. We should fund students instead of systems.

**********

Corey A. DeAngelis is the Director of School Choice at the Reason Foundation, an Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute, and the Executive Director of the Educational Freedom Institute.

References

Abdulkadiroğlu, A., Pathak, P. A., & Walters, C. R. (2018). Free to choose: can school choice reduce student achievement? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 175-206.

Anderson, K., & Wolf, P. (2017). Evaluating school vouchers: Evidence from a within-study comparison. EDRE Working Paper No. 2017-10. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2952967

Aud, S. L. (2007). Education by the Numbers: The Fiscal Effect of School Choice Programs, 1990-2006. School Choice Issues in Depth. Milton & Rose D. Friedman Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Education-by-the-Numbers-Fiscal-Effect-of-School-Choice-Programs.pdf

Barnard, C. (2019). Some People Are Buying Their Way Into Top Public Schools. That’s Not How School Choice Should Work. Reason Magazine. Retrieved from https://reason.com/2019/06/21/some-people-are-buying-their-way-into-top-public-schools-thats-not-how-school-choice-should-work/

Barnard, J., Frangakis, C. E., Hill, J. L., & Rubin, D. B. (2003). Principal stratification approach to broken randomized experiments: A case study of school choice vouchers in New York City. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 98(462), 299-323.

Bedrick, J., & Burke, L. M. (2018). Surveying Florida scholarship families: Experiences and satisfaction with Florida’s tax-credit scholarship program. EdChoice.

Bettinger, E., & Slonim, R. (2006). Using experimental economics to measure the effects of a natural educational experiment on altruism. Journal of Public Economics, 90(8-9), 1625-1648.

Betts, J. R., & Tang, Y. E. (2019). The effect of charter schools on student achievement. School choice at the crossroads: Research perspectives, 67-89.

Bitler, M., Domina, T., Penner, E., & Hoynes, H. (2015). Distributional analysis in educational evaluation: A case study from the New York City voucher program. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 8(3), 419-450.

Catt, A. D. (2020). U.S. States Ranked by Educational Choice Share, 2020. EdChoice. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/engage/u-s-states-ranked-by-educational-choice-share-2020/

Catt, A. D., & Rhinesmith, E. (2017). Why Indiana Parents Choose: A Cross-Sector Survey of Parents’ Views in a Robust School Choice Environment. EdChoice. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED579213

Chakrabarti, R. (2013). Impact of voucher design on public school performance: Evidence from Florida and Milwaukee voucher programs. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 14(1), 349-394.

Cheng, A. (2020). Myth: School choice only helps the rich get richer. In C. A. DeAngelis & N. McCluskey (Eds.), School choice myths: Setting the record straight on education freedom (pp. 113-128). Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute.

Cheng, A., Chingos, M. M., & Peterson, P. E. (2019). Experimentally Estimated Impacts of School Voucher on Educational Attainments of Moderately and Severely Disadvantaged Students. EdWorkingPaper No. 19-76. Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. E. (2014). Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. American economic Review, 104(9), 2633-79.

Chingos, M. M. (2018). The effect of the DC school voucher program on college enrollment. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/effect-dc-school-voucher-program-college-enrollment

Chingos, M. M., Monarrez, T., & Kuehn, D. (2019). The effects of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program on college enrollment and graduation: An update. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/effects-florida-tax-credit-scholarship-program-college-enrollment-and-graduation

Chingos, M. M., & Peterson, P. E. (2015). Experimentally estimated impacts of school vouchers on college enrollment and degree attainment. Journal of Public Economics, 122, 1-12.

Chubb, J. E., & Moe, T. M. (1988). Politics, markets, and the organization of schools. American Political Science Review, 82(4), 1065-1087.

Cowen, J. M. (2008). School choice as a latent variable: Estimating the “complier average causal effect” of vouchers in Charlotte. Policy Studies Journal, 36(2), 301-315.

Cowen, J. M., Fleming, D. J., Witte, J. F., Wolf, P. J., & Kisida, B. (2013). School vouchers and student attainment: Evidence from a state‐mandated study of Milwaukee’s parental choice program. Policy Studies Journal, 41(1), 147-168.

DeAngelis, C. A. (2017). Do self-interested schooling selections improve society? A review of the evidence. Journal of School Choice, 11(4), 546-558.

DeAngelis, C. A. (2018). Is Public Schooling a Public Good? An Analysis of Schooling Externalities. Policy Analysis No. 842. Cato Institute.

DeAngelis, C. A. (2019a). Divergences between effects on test scores and effects on non-cognitive skills. Educational Review, DOI: 10.1080/00131911.2019.1646707

DeAngelis, C. A. (2019b). School Sector and Satisfaction: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Sample. EdWorkingPaper No. 19-147. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. Retrieved from https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai19-147.pdf

DeAngelis, C. A. (2020a). Economic impacts of school choice in Kentucky: Understanding the impact of charter schools on Louisville. A Pegasus Institute and Reason Foundation Report. Retrieved from https://923c91f5-6c37-4af9-ac8a-aca1b179cc9c.filesusr.com/ugd/45f2de_d847380cd2ef4d04984a87159df20e4f.pdf

DeAngelis, C. A. (2020b). Funding Students Instead of Systems: The Economic Impacts of Statewide Education Savings Accounts in North Carolina. Civitas Institute. Retrieved from https://www.nccivitas.org/2020/statewide-education-savings-accounts-play-vital-role-economic-recovery-according-new-study/

DeAngelis, C. A. (2020c). Kickstarting K-12 Education in Tennessee: Avenues for Systemic Transformation. Political Economy Research Institute at Middle Tennessee State University. Retrieved from https://www.mtsu.edu/peri/docs/K12-Policy-Study.pdf

DeAngelis, C. A. (2020d). Unleashing Educational Opportunity: The Untapped Potential of Expanded Tax Credit Scholarships. Commonwealth Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/policyblog/detail/unleashing-educational-opportunity

DeAngelis, C. A., & DeGrow, B. (2018). Doing more with less: The charter school advantage in Michigan. A Mackinac Center Report. Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Flanders, W. (2018). Counting dollars and cents: The economic impact of a statewide education savings account program in Tennessee. Beacon Center of Tennessee.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Holmes Erickson, H. (2018). What leads to successful school choice programs: A review of the theories and evidence. Cato Journal, 38(1), 247-263.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Lueken, M. F. (2020). School Sector and Climate: An Analysis of K–12 Safety Policies and School Climates in Indiana. Social Science Quarterly, 101(1), 376-405.

DeAngelis, C. A., & McCluskey, N. P. (2020). School Choice Myths: Setting the Record Straight on Education Freedom. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute.

DeAngelis, C., Wolf, P., Maloney, L., & May, J. (2019). A good investment: The updated productivity of public charter schools in eight US cities. EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-09.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Wolf, P. J. (2016). Whether to Approve an Education Savings Account Program in Texas: Preventing Crime Does Pay. EDRE Working Paper No. 2016-20.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Wolf, P. J. (2019a). Private school choice and crime: Evidence from Milwaukee. Social Science Quarterly, 100(6), 2302-2315.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Wolf, P. J. (2019b). What does the evidence say about education choice? A comprehensive review of the literature. In L. M. Burke & J. Butcher (Eds.), The Not-So-Great-Society. Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation.

DeAngelis, C. A., & Wolf, P. J. (2020). Private School Choice and Character: More Evidence from Milwaukee. Journal of Private Enterprise, 35(3), 13-48.

Deming, D. J. (2011). Better schools, less crime? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 2063-2115.

Dills, A. K., & Hernández-Julián, R. (2011). More choice, less crime. Education Finance and Policy, 6(2), 246-266.

DiPerna, P., Catt, A., & Shaw, M. (2020). Schooling in America: Public Opinion on K–12 Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/research/schooling-in-america-public-opinion-on-education-during-pandemic/

Dobbie, W., & Fryer Jr, R. G. (2015). The medium-term impacts of high-achieving charter schools. Journal of Political Economy, 123(5), 985-1037.

Duchini, E., Lavy, V., & Machin, S. (2020). Youth Crime in the Era of School Takeovers. Evidence from London Secondary School Academies. Retrieved from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/educhini/duchini_lavy_machin_school_autonomy_and_youth_crime.pdf

Dyehouse, M., Benz, M., Kisa, Z., & Herrington, C. D. (2020). Parental Satisfaction and Experiences Regarding the Hope Scholarship Program 2018-19. Florida Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/5606/urlt/HopeEvalReport1819.pdf

EdChoice (2020). The 123s of school choice: What the research says about private school choice programs in America, 2020 edition. Retrieved from https://www. edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/123s-of-SchoolChoice-2020.pdf

Egalite, A. J. (2013). Measuring competitive effects from school voucher programs: A systematic review. Journal of School Choice, 7(4), 443-464.

Egalite, A. J., & Mills, J. N. (2019). Competitive impacts of means-tested vouchers on public school performance: Evidence from Louisiana. Education Finance and Policy.

Fan, W., Williams, C. M., & Corkin, D. M. (2011). A multilevel analysis of student perceptions of school climate: The effect of social and academic risk factors. Psychology in the Schools, 48(6), 632-647.

Farina, K. A. (2019). Promoting a Culture of Bullying: Understanding the Role of School Climate and School Sector. Journal of School Choice, 13(1), 94-120.

Figlio, D. N., Hart, C., & Karbownik, K. (2020). Effects of Scaling Up Private School Choice Programs on Public School Students (No. w26758). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Figlio, D., Hart, C. M., & Metzger, M. (2010). Who uses a means-tested scholarship, and what do they choose? Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 301-317.

Flanders, W., & DeAngelis, C. A. (2018). Mississippi’s game changer: The economic impacts of universal school choice in Mississippi. Mississippi State University Institute for Market Studies Working Paper.

Foreman, L. M. (2017). Educational attainment effects of public and private school choice. Journal of School Choice, 11(4), 642-654.

Friedman, M. (1955). The role of government in education. Collected Works of Milton Friedman Project records. Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford, CA.

Glenn, C. L. (1988). The myth of the common school. Univ of Massachusetts Pr.

Green, S. K. (2003). Blaming Blaine: Understanding the Blaine Amendment and the No-Funding Principle. First Amendment Law Review, 2(1), 107.

Greene, J. P. (2000). The effect of school choice: An evaluation of the charlotte children’s scholarship fund program. Civic Report, 12, 1-15.

Greene, J. P. (2001). Vouchers in Charlotte. Education Matters, 1(2), 55-60.

Greene, J. P. (2005). Education myths: What special interest groups want you to believe about our schools–and why it isn’t so. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Greene, J. P., Peterson, P. E., & Du, J. (1999). Effectiveness of school choice: The Milwaukee experiment. Education and Urban Society, 31(2), 190-213.

Hanushek, E. A. (2011). The economic value of higher teacher quality. Economics of Education Review, 30(3), 466-479.

Hart, C. M. (2014). Contexts matter: Selection in means-tested school voucher programs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(2), 186-206.

Holmes Erickson, H. (2017). How do parents choose schools, and what schools do they choose? A literature review of private school choice programs in the United States. Journal of School Choice, 11(4), 491-506.

Holmes Erickson, H., Mills, J. N., & Wolf, P. J. (2019). The effect of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on college entrance. EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-12.

Howell, W. G., Wolf, P. J., Campbell, D. E., & Peterson, P. E. (2002). School vouchers and academic performance: Results from three randomized field trials. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 21(2), 191-217.

Howell, W. G., & Peterson, P. E. (2006). The education gap: Vouchers and urban schools. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Hoxby, C. M. (2000). Does competition among public schools benefit students and taxpayers? American Economic Review, 90(5), 1209-1238.

Hoxby, C. M. (2004). Achievement in charter schools and regular public schools in the united states: Understanding the differences. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jabbar, H., Fong, C. J., Germain, E., Li, D., Sanchez, J., Sun, W. L., & Devall, M. (2019). The Competitive Effects of School Choice on Student Achievement: A Systematic Review. Educational Policy.

Jin, H., Barnard, J., & Rubin, D. B. (2010). A modified general location model for noncompliance with missing data: Revisiting the New York City School Choice Scholarship Program using principal stratification. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 35(2), 154-173.

Keller, T. (2020). Myth: Private school choice is unconstitutional. In C. A. DeAngelis & N. McCluskey (Eds.), School choice myths: Setting the record straight on education freedom (pp. 59-68). Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute.

Kelly, J. P., & Scafidi, B. (2013). More than scores: An analysis of why and how parents choose private schools. Indianapolis, IN: The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice.

Kisida, B., & Wolf, P. J. (2015). Customer satisfaction and educational outcomes: Experimental impacts of the market-based delivery of public education. International Public Management Journal, 18(2), 265-285.

Krueger, A. B., & Zhu, P. (2004). Another look at the New York City school voucher experiment. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(5), 658-698.

Ladner, M. (2020). Myth: School choice harms children left behind in public schools. In C. A. DeAngelis & N. McCluskey (Eds.), School choice myths: Setting the record straight on education freedom (pp. 97-112). Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute.

Lamarche, C. (2008). Private school vouchers and student achievement: A fixed effects quantile regression evaluation. Labour Economics, 15(4), 575-590.

Levin, H. M. (2009). The economic payoff to investing in educational justice. Educational Researcher, 38(1), 5-20.

Lleras, C. (2008). Hostile school climates: Explaining differential risk of student exposure to disruptive learning environments in high school. Journal of School Violence, 7(3), 105-135.

Lowrey, A. (2019). Her Only Crime Was Helping Her Kids. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/09/her-only-crime-was-helping-her-kid/597979/

Lueken, M. F. (2018). The fiscal effects of tax-credit scholarship programs in the United States. Journal of School Choice, 12(2), 181-215.

Lueken, M. F. (2020). The Fiscal Impact of K-12 Educational Choice: Using Random Assignment Studies of Private School Choice Programs to Infer Student Switcher Rates. Journal of School Choice.

Lueken, M. F., & Scafidi, B. (2020). Myth: School choice siphons money from public schools and harms taxpayers. In C. A. DeAngelis & N. McCluskey (Eds.), School choice myths: Setting the record straight on education freedom (pp. 79-96). Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

McCollister, K. E., French, M. T., & Fang, H. (2010). The cost of crime to society: New crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 108(1-2), 98-109.

McEachin, A., Lauen, D. L., Fuller, S. C., & Perera, R. M. (2020). Social returns to private choice? Effects of charter schools on behavioral outcomes, arrests, and civic participation. Economics of Education Review, 76(June).

Mills, J. N., & Wolf, P. J. (2019). The effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program on student achievement after four years. EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-10.

Montalbano, S. (2020). PEAKS Performance 2019: Victories for Alaska Charter Schools. Alaska Policy Forum. Retrieved from https://alaskapolicyforum.org/2020/11/peaks-2019-charter-schools/

Peterson, P. E., & Campbell, D. E. (2001). An evaluation of the Children’s Scholarship Fund. KSG Working Paper No. RWP02-020.

Rhinesmith, E. (2017). A review of the research on parent satisfaction in private school choice programs. Journal of School Choice, 11(4), 585-603.

Rouse, C. E. (1998). Private school vouchers and student achievement: An evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(2), 553-602.

Rouse, C. E., Hannaway, J., Goldhaber, D., & Figlio, D. (2013). Feeling the Florida heat? How low-performing schools respond to voucher and accountability pressure. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(2), 251-81.

Schultz, T. (2020). Support for School Choice Surges as Schools Start. RealClear Opinion Research. American Federation for Children. Retrieved from https://www.federationforchildren.org/support-for-school-choice-surges-as-schools-start/

Schwalbach, J., & DeAngelis, C. A. (2020). School sector and school safety: a review of the evidence. Educational Review, DOI: 10.1080/00131911.2020.1822789

Shakeel, M., Anderson, K., & Wolf, P. (2016). The participant effects of private school vouchers across the globe: A meta-analytic and systematic review. EDRE Working Paper No. 2017-07.

Shakeel, M. D., Anderson, K., & Wolf, P. J. (2017). The juice is worth the squeeze: A cost-effectiveness analysis of the experimental evidence on private school vouchers across the globe. In APPAM International Conference, Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from https://appam.confex.com/data/extendedabstract/appam/int17/Paper_20687_extendedabstract_1245_0. pdf.

Trivitt, J. R., & DeAngelis, C. A. (2020). Dollars and Sense: Calculating the Fiscal Effects of the Louisiana Scholarship Program. Journal of School Choice, 14(3), 349-370.

United States Census Bureau (2018). Table 11, Summary Tables, 2018 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/econ/school-finances/secondary-education-finance.html

Waasdorp, T. E., Berg, J., Debnam, K. J., Stuart, E. A., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Comparing social, emotional, and behavioral health risks among youth attending public versus parochial schools. Journal of School Violence, 17(3), 381-391.

Webber, A., Rui, N., Garrison-Mogren, R., Olsen, R., & Gutmann, B. (2019). Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts After Three Years. NCEE 2019-4006. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Witte, J. F., Wolf, P. J., Cowen, J. M., Fleming, D. J., & Lucas-McLean, J. (2008). MPCP longitudinal educational growth study: Baseline report. SCDP Milwaukee Evaluation Report# 5. School Choice Demonstration Project.

Wolf, P. J. (2007). Civics exam: Schools of choice boost civic values. Education Next, 7(3), 66-72.

Wolf, P. J. (2012). The comprehensive longitudinal evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program: Summary of final reports. School Choice Demonstration Project, University of Arkansas.

Wolf, P. J. (2018). Programs benefit disadvantaged students. Education Next, 18(2).

Wolf, P. J. (2020). Myth: Public schools are necessary for a stable democracy. In C. A. DeAngelis & N. McCluskey (Eds.), School choice myths: Setting the record straight on education freedom (pp. 39-58). Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute.

Wolf, P. J., Gutmann, B., Puma, M., Kisida, B., Rizzo, L., & Eissa, N. (2008). Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Impacts after Two Years. Executive Summary. NCEE 2008-4024. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Wolf, P. J., Gutmann, B., Puma, M., Kisida, B., Rizzo, L., Eissa, N., & Carr, M. (2010). Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Final Report. NCEE 2010-4018. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED510451

Wolf, P. J., Hitt, C., & McShane, M. Q. (2018). Exploring the achievement-attainment disconnect in the effects of school choice programs. Paper presented at the conference “Learning from the Long-Term Effects of School Choice in America” Program on Education Policy and Governance, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/pepg/conferences/learning-from-longterm-effects-2018/papers/panel-ii-wolf-et-al.pdf

Wolf, P. J., Cheng, A., Batdorf, M., Maloney, L. D., May, J. F., & Speakman, S. T. (2014). The productivity of public charter schools. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/scdp/6/

Wolf, P. J., Kisida, B., Gutmann, B., Puma, M., Eissa, N., & Rizzo, L. (2013). School Vouchers and Student Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Washington, DC. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(2), 246-270.

Wolf, P. J., & McShane, M. (2013). Is the juice worth the squeeze? A benefit/cost analysis of the District of Columbia opportunity scholarship program. Education Finance and Policy, 8(1), 74-99.

Wolf, P. J., Witte, J. F., & Kisida, B. (2019). Do voucher students attain higher levels of education? Extended evidence from the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. EdWorkingPaper No. 19-115. Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Zimmer, R., Buddin, R., Smith, S. A., & Duffy, D. (2019). Nearly three decades into the charter school movement, what has research told us about charter schools? EdWorkingPaper No. 19-156. Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Endnotes

[1] Alaska is a resource extraction state. From oil and gas, to mining and fishing, nearly all state revenues come from direct taxes on those activities or from investment earnings on those revenues. Unlike most other states, it is those resource extraction industries which are the primary “taxpayers” in Alaska.

[2] What is an Education Savings Account? EdChoice. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/types-of-school-choice/education-savings-account/

[3] The latest data reported by the National Center for Education Statistics shows that Alaska spent around $19,396 per student in K-12 public schools in the 2016-17 school year. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_236.75.asp?current=yes

[4] Table 11, Summary Tables. 2018 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/econ/school-finances/secondary-education-finance.html

[5] Alaska Private Schools By Tuition Cost. Private School Review. Retrieved from https://www.privateschoolreview.com/tuition-stats/alaska

[6] School Districts’ Reopening Plans: A Snapshot. Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/school-districts-reopening-plans-a-snapshot.html

[7] Fairbanks teachers unions denounce school reopening plan. Alaska Public Media. Retrieved from https://www.alaskapublic.org/2020/12/22/fairbanks-teachers-unions-denounce-school-reopening-plan/

[8] Private Schools Are Adapting to Lockdown Better Than the Public School Monopoly. Reason Magazine. Retrieved from https://reason.com/2020/07/17/private-schools-are-adapting-to-lockdown-better-than-the-public-school-monopoly/

[9] COVID-19 Didn’t Break the Public School System. It Was Already Broken. Reason Magazine. Retrieved from https://reason.com/2020/11/03/covid-19-didnt-break-the-public-school-system-it-was-already-broken/

[10] Students, parents migrate to homeschool classes. Must Read Alaska. Retrieved from https://mustreadalaska.com/students-parents-migrate-to-homeschool-classes/

[11] Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools. 2018-2019 Statewide Results. Alaska Department of Education & Early Development. Retrieved from https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Statewide/StatewideResults?schoolYear=2018-2019&isScience=False

[12] Alaska Overview. The Nation’s Report Card. Retrieved from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/profiles/stateprofile/overview/AK

[13] America’s Gradebook: How Does Your State Stack Up? Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://apps.urban.org/features/naep/

[14] School Choice – District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program. EdChoice. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/district-of-columbia-opportunity-scholarship-program/

[15] Table 11, Summary Tables. 2018 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/econ/school-finances/secondary-education-finance.html

[16] DeAngelis, C. A. (2019). School choice works – for a third of the cost. Washington Examiner. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/school-choice-works-for-a-third-of-the-cost

[17] Chetty, Friedman, and Rockoff (2014) found similar results to Hanushek (2011). The estimated relationship between academic achievement and lifetime earnings found by Chetty, Friedman, and Rockoff (2014) only differed from Hanushek (2011) by around two-percentage points.

[18] May 2019 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates – Alaska. Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_ak.htm

[19] Catt, D. (2020). U.S. states ranked by educational choice share, 2019. EdChoice. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/engage/u-s-states-ranked-by-educational-choice-share-2020/

[20] Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools. Table 203.20. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_203.20.asp?current=yes

[21] The 5 percent participation rate is based on data from the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program when it was launched in 2004-05 and the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program when it was expanded in 1998-99 (DeAngelis & Wolf, 2016; Wolf et al., 2008; Wolf, 2012).