A Case Study of Maine and Analysis of 96 Other Jurisdictions

Click here to open a PDF of the report in a new tab. The PDF includes the Appendix.

Introduction

A movement currently sparking interest across the country, including in Alaska, is called ranked-choice voting (RCV), also known as instant run-off voting (IRV). Several U.S. municipalities have experimented with ranked-choice voting for more than a decade. For example, the City of San Francisco, California has been using ranked-choice voting since 2004.[1] Via a 2016 ballot initiative, Maine launched a bold experiment by becoming the first state to adopt ranked-choice voting statewide. This case study has been created using data previously compiled by the Maine Policy Institute from those municipal elections and Maine. The results analyzed are from 96 elections in the U.S. that triggered ranked-choice voting. Put differently, these election results were compiled from 96 races where more than one round of tabulation occurred.

A movement currently sparking interest across the country, including in Alaska, is called ranked-choice voting (RCV), also known as instant run-off voting (IRV). Several U.S. municipalities have experimented with ranked-choice voting for more than a decade. For example, the City of San Francisco, California has been using ranked-choice voting since 2004.[1] Via a 2016 ballot initiative, Maine launched a bold experiment by becoming the first state to adopt ranked-choice voting statewide. This case study has been created using data previously compiled by the Maine Policy Institute from those municipal elections and Maine. The results analyzed are from 96 elections in the U.S. that triggered ranked-choice voting. Put differently, these election results were compiled from 96 races where more than one round of tabulation occurred.

Using this data, we can examine and draw conclusions about ranked-choice voting and compare Maine’s most recent experience with other jurisdictions to identify patterns. The goal of this report is to analyze the history, claims, and mechanisms of ranked-choice voting in an attempt to understand how the system works, its merits and shortcomings, and how it compares to plurality elections and other voting systems.

How Does Ranked-Choice Voting Work?

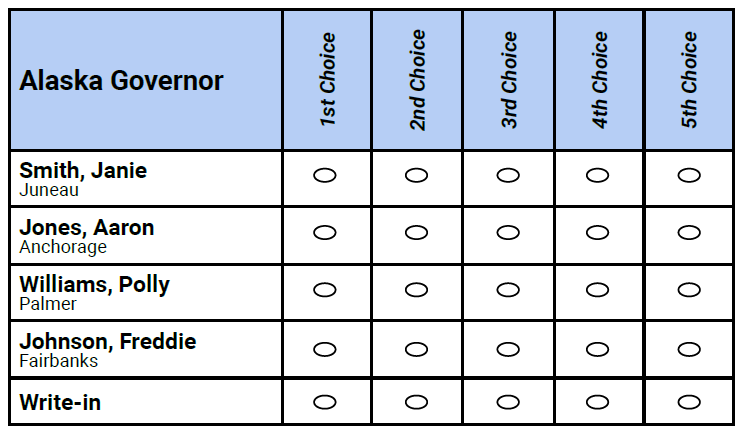

In contrast to plurality elections where voters select a single candidate and the candidate with the most votes wins, ranked-choice voting gives voters the option to rank-order candidates on their ballots. For example, voters may have the choice to rank up to four candidates on their ballots.

In contrast to plurality elections where voters select a single candidate and the candidate with the most votes wins, ranked-choice voting gives voters the option to rank-order candidates on their ballots. For example, voters may have the choice to rank up to four candidates on their ballots.

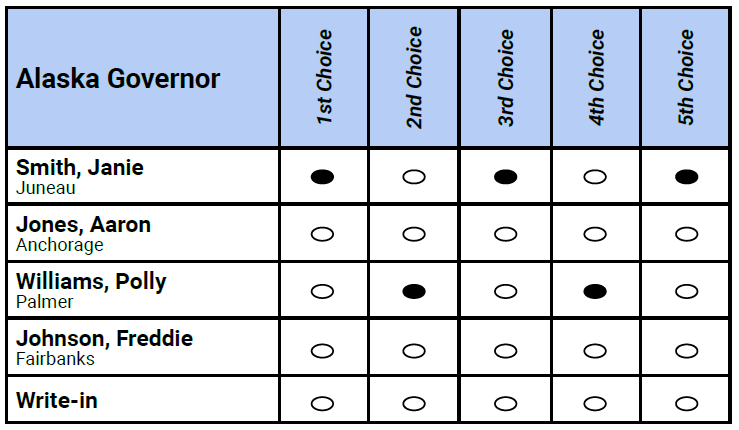

If a candidate receives more than 50 percent of first-place votes, they are declared the winner of the election. However, oftentimes one candidate does not receive a majority of the votes cast on Election Day. When this occurs, the candidate(s) who do not stand a mathematical chance of winning are eliminated from contention, and additional rounds of tabulation occur until a candidate receives a majority of the remaining votes. If Janie Smith was eliminated from contention after the first round of tabulation, then the ballots that listed her as a voter’s first choice are then awarded to the candidate listed as the voter’s next choice. This recurs until one candidate receives over 50 percent of the leftover, non-exhausted ballots. In some races, it may only take one or two rounds of tabulation to declare a winner. However, races with a large field of candidates can require many rounds of tabulation. Regardless, most ranked-choice voting elections that have more than one round of tabulation produce exhausted ballots.

What is an Exhausted Ballot?

An exhausted ballot occurs when a voter overvotes, undervotes, or ranks only candidates that are eliminated from contention. Because these votes are not tabulated in the final round, that ballot does not influence the election after it becomes exhausted. For example, if a ballot becomes exhausted in round four of an election that necessitates 20 rounds of tabulation, the voter’s ballot is not included in the final tally; it is as if they never showed up on Election Day. Below are definitions for each type of exhausted ballot:

Overvote

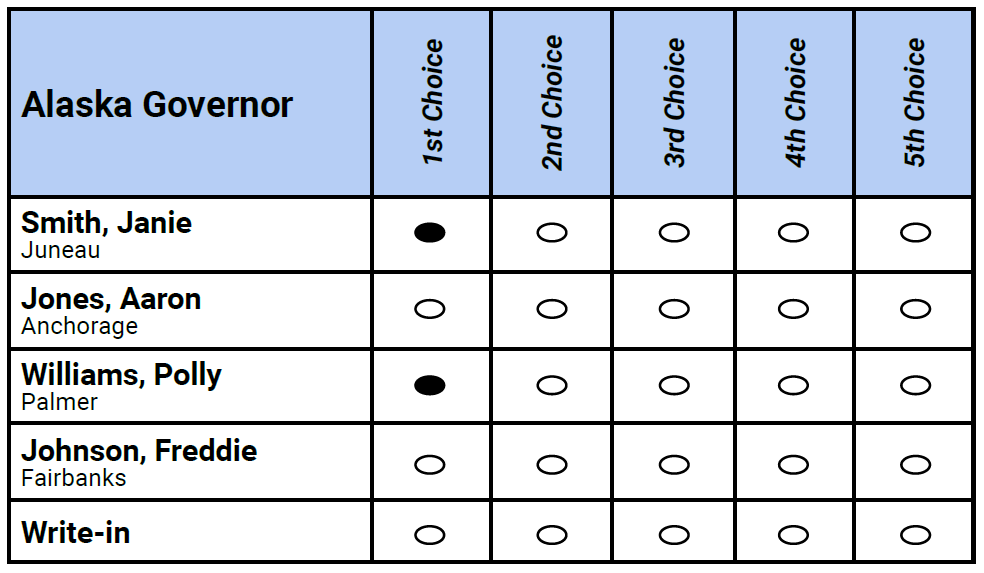

An overvote occurs when a voter marks two candidates in a single column/rank. For example, if a voter marked both Janie Smith and Aaron Jones as his first choice, his ballot would not count in the election. Likewise, if a voter correctly ranked his first choice but marked two candidates in the following column, only the first choice would be tabulated.

Undervote

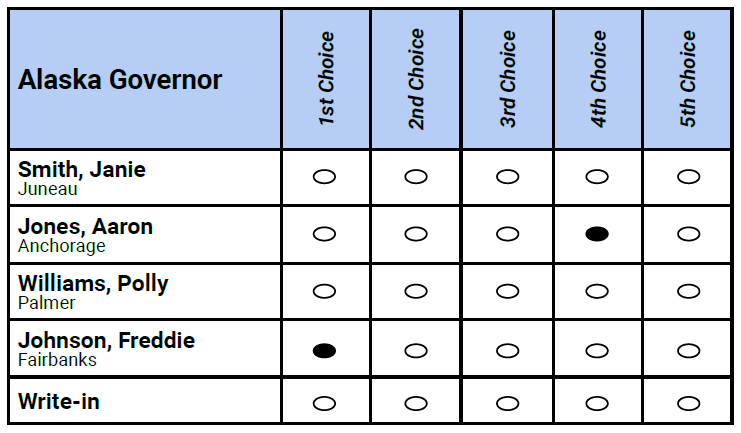

An undervote occurs when a voter skips two or more columns or rankings. For example, if a voter picked Janie Smith as his first choice, skipped his second and third choice and selected another candidate as his fourth choice, his ballot would not count in the election after the first round.

Exhausted Choices

An exhausted choice occurs when a voter ranks only candidates that are eliminated from contention. For example, a voter may only rank Janie Smith and Polly Williams, even if they are eventually eliminated after round one of tabulation.

For the purpose of this report, the distinction between exhausted ballots in the first round of tabulation and the rest of the election merits clarification. In this report, we do not consider overvotes and undervotes in the first round of tabulation as “exhausted votes” because voters could make the same mistake on a ballot in an election decided by plurality. In other words, votes that are exhausted in the second and subsequent rounds of tabulation are purely a consequence of using ranked-choice voting. Thus, this report will focus on and isolate those exhausted ballots.

Voter Confusion and Information Deficits

In a plurality election, the choice facing voters is simple: Of all the candidates running, whom do you prefer?

Ranked-choice voting entails a much more complicated — and somewhat artificial — decision. To fully participate, voters must rank-order all of the candidates. In contrast to run-off elections, voters do not get the benefit of evaluating candidates as they face-off one-on-one. In Maine, voter confusion was so pervasive that proponents of ranked-choice voting felt the need to publish a 19-page instruction manual to help voters navigate the process.[2]

This inherent feature of ranked-choice voting is problematic because it demands that voters have a large amount of information about candidates’ differing views. The fact is that most Alaska voters, like most voters in any election, do not follow political races closely enough to meaningfully rank multiple candidates. Yet in order to avoid losing influence in a ranked-choice voting election, a voter must rank each and every candidate. A voter, even one without strong feelings for or against certain candidates, may feel pressured to rank them anyway based on little more than random chance. It is impossible to know exactly how many voters in ranked-choice elections feel this way since nothing can be inferred from how they filled out their ballots, but this phenomenon is likely common.

It is well documented that American voters often lack basic information about candidates’ policy positions. A Pew Research Center survey conducted shortly before the 2016 presidential election revealed that a significant proportion of registered voters knew little or nothing about where the two major candidates stood on key issues.[3] For instance, 48 percent of all voters knew a lot about Hilary Clinton’s positions, 32 percent knew some, and 18 percent knew not much or nothing. Knowledge about Donald Trump’s stances was even lower: 41 percent of all voters knew a lot about his positions, 27 percent knew some, and 30 percent knew little or nothing.[4] In 2018, a poll found that 34 percent of registered Republican voters and 32.5 percent of registered Democratic voters said they did not even know the names of their party’s congressional candidates in their districts.[5]

In other words, tens of millions of Americans enter the voting booth knowing virtually nothing about the policy stances of the candidates. It seems unlikely that they could confidently rank multiple candidates based on a sound assessment of their platforms. A 2014 study conducted in California provides additional reasons to be skeptical that ranked-choice voting functions in practice as its proponents predict.[6] The study found voters are “largely ignorant about the ideological orientation of candidates, including moderates.”[7] This information deficit is already a concern in plurality contests and is greatly magnified in ranked-choice voting elections when voters are asked to rank more than a single candidate.

Less knowledgeable voters are more likely to rank fewer candidates, potentially denying them influence over the election outcome. Giving knowledgeable voters more electoral influence may be defensible as a matter of political philosophy, but it is surely not the intent behind adoption of ranked-choice voting.

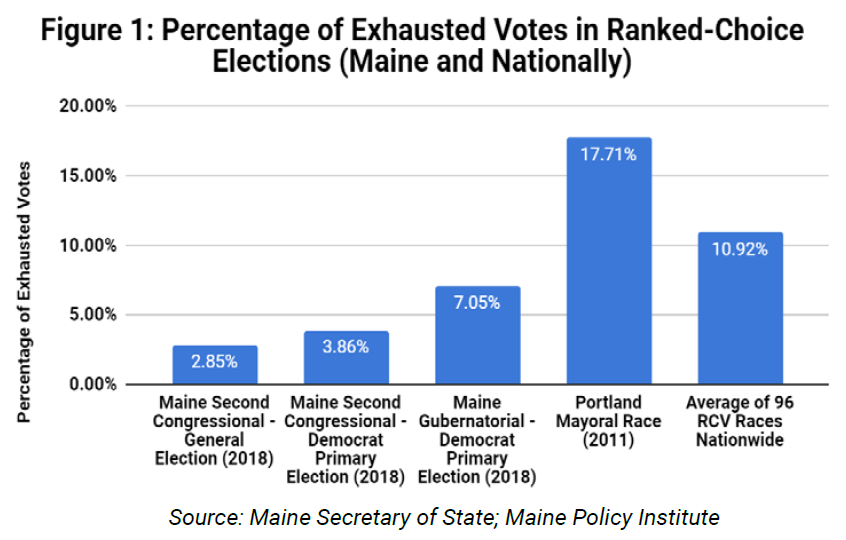

The 2018 Maine Democratic gubernatorial primary provides a good example of the practical challenges this poses to voters in ranking their preference in a large field of candidates. There were seven candidates on the ballot in this race and more than seven percent of the ballots were exhausted by the end of the fourth round of tabulation.[8] Another example is the 2011 mayoral race in Portland, where ranked-choice voting was used, and 15 candidates appeared on the ballot. In this race, voters had 15 choices, and almost 18 percent of the votes were exhausted before a winner was determined.[9]

When the 96 ranked-choice voting races from across the nation were analyzed, the results show an average of 10.92 percent of ballots cast are exhausted by the final round of tabulation. This phenomenon can be seen in Figure 1.

When presented with a ranked-choice voting ballot, many voters do not rank every candidate, potentially due to insufficient information about the candidates or confusion about how ranked-choice voting works. Exhausted ballots are a serious problem under ranked-choice voting, as they systematically reduce the electoral influence of certain voters. A study in 2014 reviewed more than 600,000 ballots in four municipal ranked-choice voting elections from around the country and found ballot exhaustion to be a persistent and significant feature of these elections.[10] The rate of ballot exhaustion in that study was high in each election, ranging from 9.6 percent to 27.1 percent.

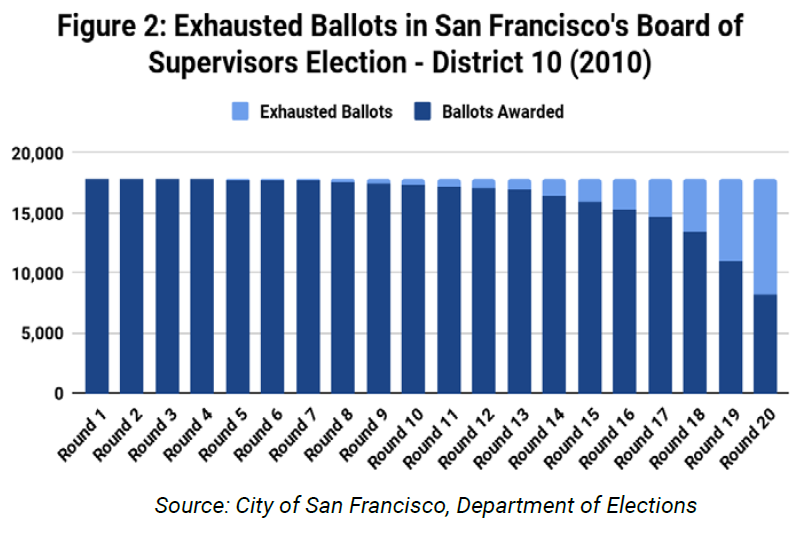

While exceedingly rare, ranked-choice voting races can create more exhausted ballots than ballots that are awarded to the winner of an election. For example, the 2010 election for San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors in District 10 resulted in 9,608 exhausted ballots whereas the prevailing candidate only received 4,321 votes.[11] More striking, there were 1,300 more ballots that were exhausted than were awarded to a candidate at the end of the 20th round of tabulation.[12] This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 2.

Voter Disenfranchisement

When voters are confused by the election process, their voices can be stifled. There is evidence that ranked-choice voting results in voter disenfranchisement.

After San Francisco’s 2004 ranked-choice voting election, a study conducted by FairVote, a proponent of ranked-choice voting, found that “the prevalence of ranking three candidates was lowest among African Americans, Latinos, voters with less education, and those whose first language was not English.”[13] In the races examined in FairVote’s study, the ballots had three columns for voters to rank their candidates of choice. African Americans, Latinos, voters with less education, and those whose first language was not English disproportionately did not utilize their ballot to the fullest extent possible. More specifically, only 50 percent of African Americans and 53 percent of Latinos ranked three candidates whereas 62 percent of whites ranked a candidate in all three columns. The results of this study are of particular significance in Alaska, where it is required to provide language assistance and ballots for at least 13 other languages for those voters whose primary language is not English.[14]

After San Francisco’s 2004 ranked-choice voting election, a study conducted by FairVote, a proponent of ranked-choice voting, found that “the prevalence of ranking three candidates was lowest among African Americans, Latinos, voters with less education, and those whose first language was not English.”[13] In the races examined in FairVote’s study, the ballots had three columns for voters to rank their candidates of choice. African Americans, Latinos, voters with less education, and those whose first language was not English disproportionately did not utilize their ballot to the fullest extent possible. More specifically, only 50 percent of African Americans and 53 percent of Latinos ranked three candidates whereas 62 percent of whites ranked a candidate in all three columns. The results of this study are of particular significance in Alaska, where it is required to provide language assistance and ballots for at least 13 other languages for those voters whose primary language is not English.[14]

When individuals leave columns blank on their ballots, and the candidate(s) they vote for are eliminated from contention, their ballots are not counted in the final tabulation. Therefore, if these voters only choose one candidate on their ballots, they are more likely to become exhausted, thereby giving those who fully complete their ballots more influence over the electoral process. In other words, African Americans, Latinos, voters with less education, and those whose first language is not English are more likely to be disenfranchised with a ranked-choice voting system.

Further, in his analysis of San Francisco elections between 1995 and 2001, Jason McDaniel, an associate professor at San Francisco State University, found that ranked-choice voting is likely to decrease voter turnout, primarily among African Americans and white voters.[15] McDaniel also found that ranked-choice voting increases the disparity between “those who are already likely to vote and those who are not, including younger voters and those with lower levels of education.”[16] In short, the complexity of a ranked-choice ballot makes it less likely that disadvantaged voices will be fully heard in the political and electoral process.[17]

One key question is whether the rate of ballot exhaustion declines as ranked-choice voting becomes an accepted practice in a jurisdiction and voters become acclimated to it. Evidence suggests that, although mistake rates may decline slightly over time, ranked-choice voting produces consistently higher proportions of exhausted ballots than plurality elections. The data from races in San Francisco showed inconsistent results — some districts showed higher rates of exhausted ballots over time while others realized a decline. In Australia, which has used ranked-choice voting in its legislative elections for more than a century, officials still report a much higher rate of invalid ballots than comparator countries like the United States.[18]

While confusion at the ballot box is difficult to quantify, the large percentage of exhausted ballots after the first round of tabulation in ranked-choice voting elections is troubling. It is clear that plurality elections do not elicit as many exhausted ballots. In addition, it is easier for voters to understand and participate in plurality elections. In short, policymakers should make voting as simple as possible and strive to increase engagement in our electoral process.

Claims Made by Proponents of Ranked-Choice Voting

Too often, proponents of ballot initiatives advance lofty claims to win support at the ballot box. Below are some of the claims made by proponents of ranked-choice voting and how they measure up to the data.

Claim 1: A Candidate Needs a Majority to Win

Proponents of ranked-choice voting often claim that “in a ranked-choice election, a candidate needs to earn more than half of the votes to win.”[[19]] While this might seem logical based on the sequence of events in a ranked-choice election, it does not always hold true. In fact, a candidate in Maine in 2018 prevailed in a ranked-choice election without receiving a true majority of the votes cast.

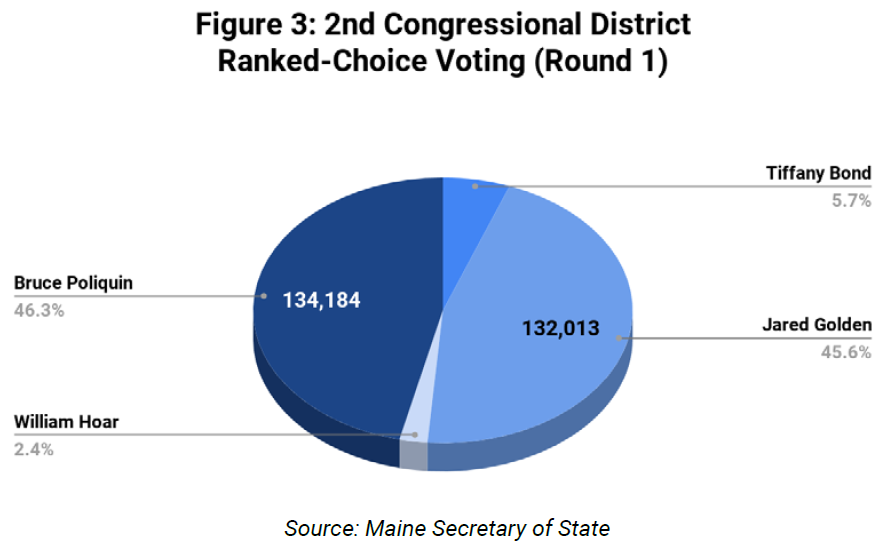

In Maine’s 2018 Second Congressional District election, incumbent Bruce Poliquin won a plurality (46.33 percent) in the first round of voting. Because the election was governed by ranked-choice voting and Poliquin had not earned more than 50 percent of the votes cast, a second round of tabulation was conducted and the candidates who could not mathematically win were eliminated from contention.

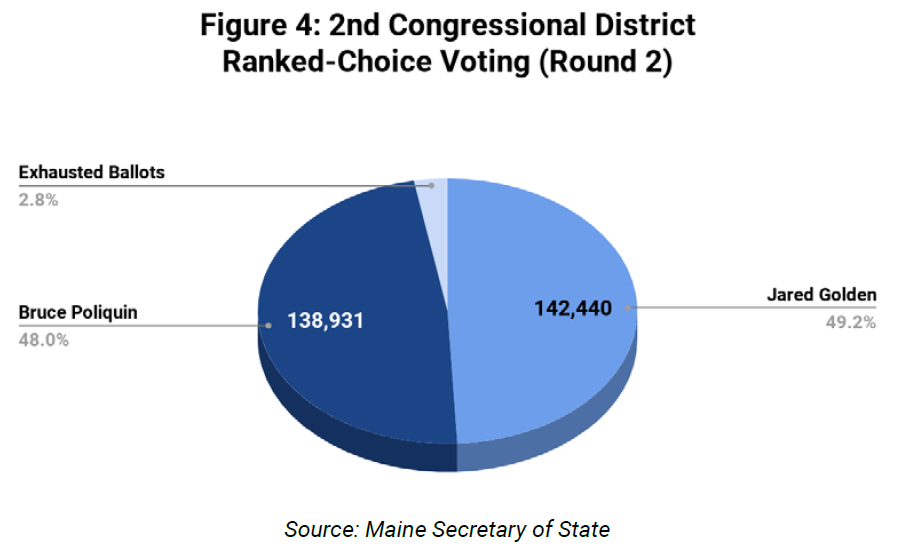

In the second round, Jared Golden secured victory after he gained enough votes from the eliminated candidates to eclipse Poliquin’s lead. However, in this case, “majority” is a misnomer. In reality, Golden prevailed with only 49.18 percent of the total votes cast in the election. This phenomenon is due to the number of ballots that were exhausted during the reallocation of votes from the candidates who were eliminated after the first round.

To come to this conclusion, one must look at the total number of votes cast in the first round of the election, which was 289,624. After enough ballots were exhausted, Jared Golden was declared the winner with 142,440 votes.[20] However, this was only the majority of the votes tallied in the second round of tabulation, which totaled 281,375. Thus, 8,253 votes were exhausted after the first round and were not carried over into the second round. Figures 3 and 4 outline the distribution of votes in each round of tabulation.

To come to this conclusion, one must look at the total number of votes cast in the first round of the election, which was 289,624. After enough ballots were exhausted, Jared Golden was declared the winner with 142,440 votes.[20] However, this was only the majority of the votes tallied in the second round of tabulation, which totaled 281,375. Thus, 8,253 votes were exhausted after the first round and were not carried over into the second round. Figures 3 and 4 outline the distribution of votes in each round of tabulation.

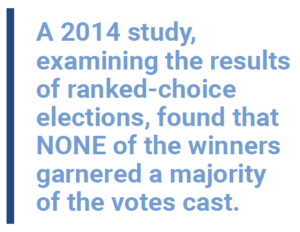

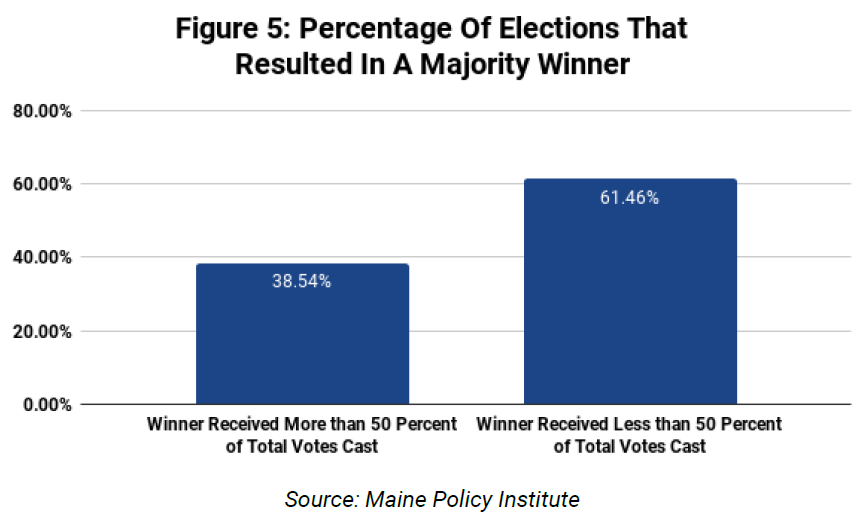

Further, peer-reviewed research points to the lack of a majority winner as a crucial flaw in the ranked-choice voting system. A 2014 study revealed that ranked-choice voting does not always produce a majority winner. In fact, none of the winners of the elections examined in the study won with a majority of the votes cast.[21] In examining 96 ranked-choice voting races from across the country where additional rounds of tabulation were necessary to declare a winner, the data shows that the eventual winner failed to receive a true majority 61 percent of the time. This can be seen in Figure 5. The most extreme example was from the 2010 San Francisco District 10 Board of Supervisors race, where the prevailing candidate received fewer than 25 percent of the votes cast.

Thus, the claim that ranked-choice voting always provides a majority winner because a candidate is required to earn more than 50 percent of the vote is false and deserves further scrutiny from voters. While candidates sometimes do receive a majority of the total votes cast, a winner is often declared only after a large number of exhausted ballots have been removed from the final denominator.

Claim 2: Ranked-Choice Voting Reduces Negative Campaigning and Mitigates the Impact of Money in Politics

Ranked-choice voting is often presented as a solution to the bitter, divisive campaign rhetoric that has come to characterize much of politics in Alaska and the nation.[22] The argument goes like this: Since candidates hope to be the second choice of voters who prefer a rival candidate, all candidates are dissuaded from trashing their opponents and alienating potentially crucial voters.

But while this logic may discourage candidates from attacking each other directly, it may also augment the role of unaccountable third-party groups in negative campaigning. Recent analysis could not test whether the candidates themselves reduced negative campaigning because the Federal Elections Commission does not compile data related to expenditures in opposition or support of a candidate from the principal campaign committees.

As empirical evidence of the claim that ranked-choice voting makes elections more civil, advocates point to a survey of voters conducted in 2014 in several U.S. cities that used ranked-choice voting to elect city officials.[23] While this study does suggest that negativity declines with ranked-choice voting, it simply measures the “perception of campaign cooperation and civility” and was conducted through a telephone survey. In addition, the sample size was relatively small — measuring only 2,400 respondents in several municipalities. The conclusion that ranked-choice voting decreases negative campaigning merits additional scrutiny.

We can test proponents’ claims with campaign finance data from Maine’s 2018 gubernatorial primaries and the Second Congressional District general election, two of the more recent elections that occurred via RCV. The largest limitation to this research is that independent expenditures below $250 do not have to be reported to the Maine Ethics Commission, so some campaign spending is not captured in the analysis.[24]

Maine’s Gubernatorial Primaries

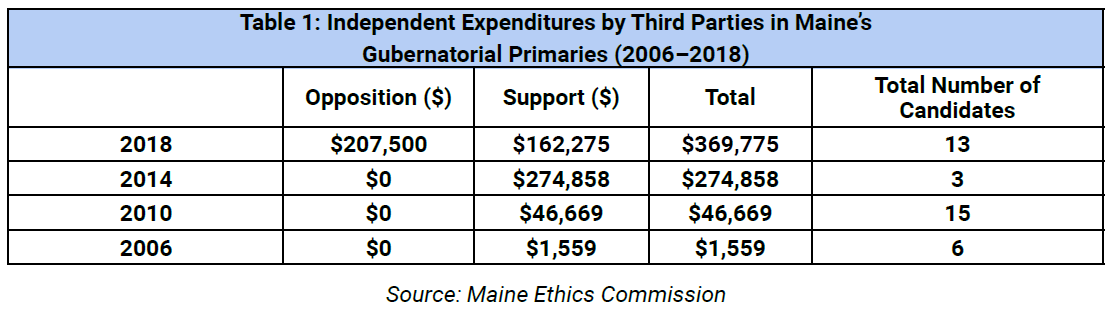

In Maine’s 2018 gubernatorial primaries, there was a clear increase in independent expenditures (spending by third-party groups unaffiliated with a particular candidate or party) when compared to prior gubernatorial primaries. In 2018, a total of $207,500 was spent through independent expenditures to oppose specific candidates. Similarly, $146,775 was spent through independent expenditures to support candidates in the 2018 gubernatorial primaries.

While this may seem insignificant for gubernatorial races, it must be pointed out that there were zero independent expenditures in opposition to specific candidates during the 2006, 2010, and 2014 gubernatorial primaries.[25] Of these elections, the 2010 gubernatorial race most closely resembles the 2018 election because of the large field of candidates and the fact that the incumbent was term limited out of office, making it an open seat.

As outlined in Table 1, there were zero independent expenditures in opposition to a candidate in 2010 and only $46,669 was spent in support of a candidate. In contrast, $207,500 was spent in opposition to a candidate in 2018 and $146,775 was spent in support. Support expenditures actually decreased by more than 40 percent from 2014 to 2018 while opposition expenditures increased from $0 to $207,500.

According to fundraising data from the Maine Ethics Commission, 2018 Democrat gubernatorial candidate Adam Cote had raised over $1 million in the primary election whereas candidate Janet Mills hovered around $792,000 before June 12, 2018. Instead of Mills’ campaign attacking Cote directly, it may have been more effective for her to allow third-party groups to launch attacks against Cote to avoid tarnishing her image in the eyes of Cote supporters. That is exactly what happened — $192,500 of the opposition spending came from Maine Women Together to attack Cote for once being a Republican and accepting corporate donations.[26] Since a third-party group was levying attacks on Cote, it was more plausible that Mills would receive his voters’ second choice votes if he was eliminated from contention than if she attacked him through her own campaign channels.

Unfortunately, this analysis is limited by the records that were available from the Maine Ethics Commission. Records for gubernatorial races prior to 2006 are unavailable.

Maine’s 2018 Second Congressional Race

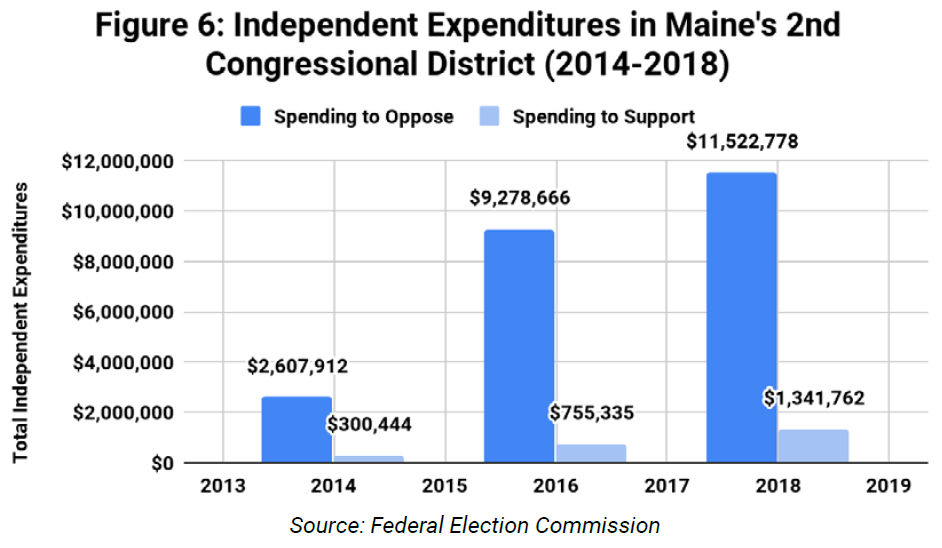

A similar phenomenon occurred in Maine’s 2018 Second Congressional District election, which was the first general election in Maine where RCV was law.[27] According to Federal Election Commission data, approximately $11.52 million was spent through independent expenditures in opposition to a candidate in the 2018 Second Congressional District race. This was a 24 percent increase from 2016, which saw $9.27 million spent on opposition expenditures.

When the opposition expenditures in non-presidential elections (2014 and 2018) are compared, recent analysis found that opposition expenditures increased by 341 percent. Only $2.91 million was spent on independent expenditures to oppose a candidate in 2014. Figure 6 breaks down the amounts spent through independent expenditures in support and opposition to candidates in the Second Congressional District.

While this analysis does not provide sufficient evidence that ranked-choice voting increases negative campaigning by third-party groups, it casts doubt on the claim that ranked-choice voting improves the tone and civility of political races. This data should be interpreted as a preliminary indication that ranked-choice voting does not reduce negative campaigning.

Claim 3: Ranked-Choice Voting Will Increase Turnout

A common metric used to judge the performance of a voting system — although by no means the only criterion — is its impact on voter turnout. In a democratic society, public participation in elections is critical. A voting system that, for whatever reason, discourages a large portion of eligible voters from casting a ballot could hardly claim to reflect the will of the people.

By international standards, voter turnout in the United States is low.[28] In the 2018 midterms, only 50.3 percent of eligible voters nationwide cast a ballot, and even that level of engagement marked a 50-year high for a midterm election.[29] Alaska performed better than the national average, with turnout at 54.6 percent in 2018.

Of course, the United States’ comparatively low voter turnout has a multitude of causes. Cultural differences, barriers to voter registration, political party dynamics, the competitiveness of races, and other factors influence voter turnout.

Some argue that ranked-choice voting could improve America’s chronically low levels of citizen participation in elections by making voters feel that their voice has a greater impact on the outcome of the election. On the other hand, ranked-choice voting might depress turnout by discouraging voters who are confused about how to vote or who don’t feel knowledgeable enough to make an informed decision. By increasing the complexity of the ballot, ranked-choice voting could also make it harder for voters to understand the connection between any one vote they cast and the resulting impact on government policies.

The empirical evidence is mixed but tends to show that ranked-choice voting slightly depresses turnout relative to plurality elections. It is important to note that ranked-choice voting has been tried in a small number of jurisdictions in the U.S., which limits the sample size and reduces the power of statistical analyses. It is also exceedingly difficult to isolate other variables — such as voter enthusiasm generated by specific candidates and other concurrent election reforms — that can play a major role in voter turnout.

A study of four cities in California that adopted ranked-choice voting in the early 2000s found that “voter turnout has remained stable when compared to previous elections.”[30] In contrast, testimony to the Kansas Special Committee on Elections from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) said:

Ranked-choice ballots have suppressed voter turnout, especially among those segments of the electorate that are already least likely to participate. Ranked-choice voting (RCV) has resulted in decreased turnouts up to 8% in non-presidential elections. Low-propensity voters are already less likely to participate in elections that do not coincide with congressional or presidential races. By adding additional steps to voting, RCV exacerbates this tendency, making it less likely that new and more casual voters will enter into the process. Moreover, RCV exacerbates economic and racial disparities in voting. Voting errors and spoiled ballots occur far more often. In Minneapolis, for example, nearly 10% of ranked choice ballots were not counted, most of these in low-income communities of color. Other municipalities have seen similar effects.[31]

Proponents of ranked-choice voting point to an analysis commissioned by FairVote that found ranked-choice voting is associated with a 10-point increase in voter turnout compared to primary and run-off elections, but is not associated with any change in turnout in general elections. The study was based on data from 26 American cities across 79 elections.[32] According to the study, this 10-point “increase” in turnout is likely due to the compression of voting and “winnowing” of candidates into one election.[33] Overall, the study suggested that ranked-choice voting elections have “minimal effects on rates of voter participation.”[34]

As previously mentioned, a study of San Francisco’s election data from 1995 to 2011 found that turnout declined among African American and white voters and exacerbated the disparities between voters who were already likely to vote and those who were not.[35] The author attributes these effects, at least in part, to the fact that ranked-choice voting increases the “information costs” of voting (i.e., the need to be familiar with how ranked-choice voting works further discourages low-propensity voters from participating in elections).[36] Exit polls of voters participating in ranked-choice voting bolster these findings.[37]

Since the answer to whether ranked-choice voting actually increases turnout when compared to plurality elections is still up for debate, it is irresponsible to make this lofty claim.

Comparing Election Outcomes

A relevant question in comparing plurality elections against ranked-choice voting is to ask how often the two voting systems would produce a different electoral outcome. Those cases are relatively sparse, occurring only when the votes cast for eliminated candidates are reallocated to a contender who came in second place or worse in the first round of tabulation, and the votes gained in subsequent rounds of tabulation exceed the gains made by the leader after the first round.

Maine

In 2018, only three elections in Maine had no majority winner in the first round of votes:

- Democrat Gubernatorial Primary

- Democrat Congressional Primary (Second Congressional District)

- General Election for the Second Congressional District

Of the elections that required additional rounds of tabulation in Maine, the general election race for the Second Congressional District was the only election that produced an outcome different than what would have occurred under a plurality election.

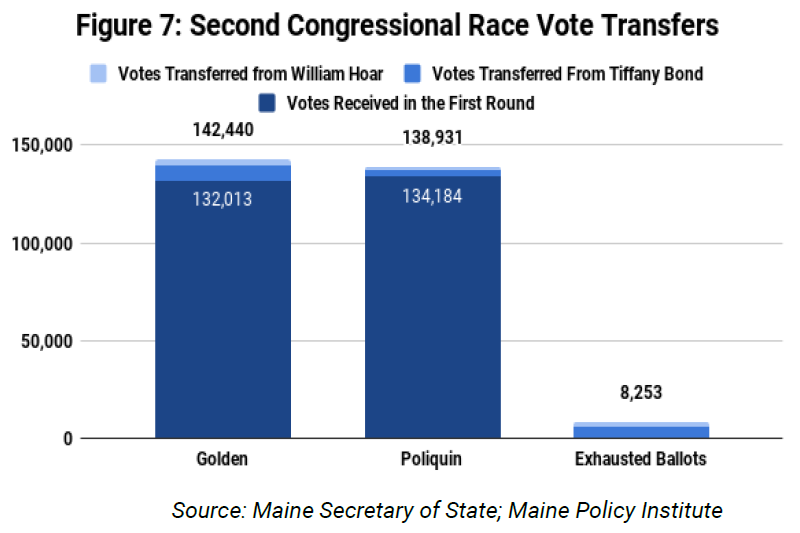

As previously mentioned, Poliquin initially received 134,184 votes, or 46.33 percent of the total votes cast whereas Golden received 132,013 votes, or 45.48 percent of the total votes cast. Once the second round of tabulation was completed, 4,747 votes (3,117 from Bond and 1,630 from Hoar) were allocated to Poliquin and 10,427 votes (7,862 from Bond and 2,565 from Hoar) were awarded to Golden. Figure 7 provides a visual breakdown of how the votes were distributed to change the outcome of the election.

Other Jurisdictions

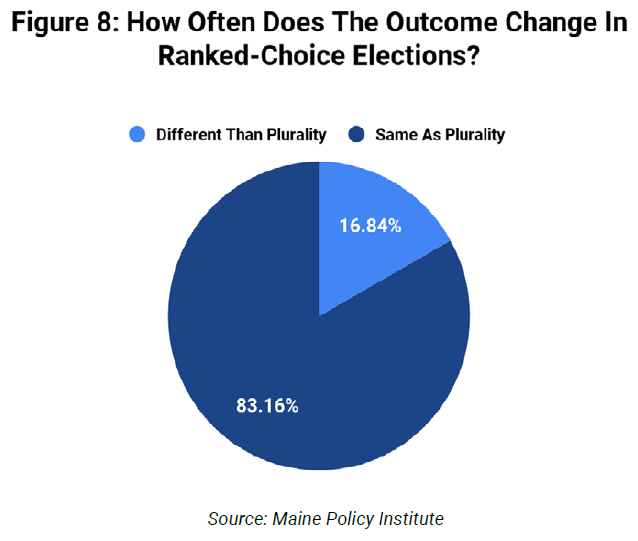

According to the election results obtained from 96 ranked-choice voting elections nationwide that triggered a second round of tabulation (excluding one that resulted in a tie in the first round of tabulation), ranked-choice voting changes the outcome of an election approximately 17 percent of the time. This is illuminated in Figure 8. If all ranked-choice voting races were examined in this analysis, including those that produced a majority winner in the first round, the percentage of races where the outcome changes would decrease.

The frequency with which ranked-choice voting elections produce a different outcome than plurality elections is important because it allows lawmakers to weigh the benefits and consequences of a new voting system. If ranked-choice elections rarely produce a different outcome, the costs of such a system may outweigh the alleged benefits.

Paradoxical Effects of Ranked-Choice Voting

One of the primary arguments in favor of ranked-choice voting is that it gives voters a broader set of options and reduces political polarization. However, these claims overlook serious shortcomings of ranked-choice voting.[38]

Ranked-choice voting exhibits non-monotonicity, one of the fundamental metrics used by political theorists to evaluate voting systems. Monotonicity is defined as follows: “With the relative order or rating of the other candidates unchanged, voting a candidate higher should never cause the candidate to lose, nor should voting a candidate lower ever cause the candidate to win.” In other words, voting your choice should only help your candidate.

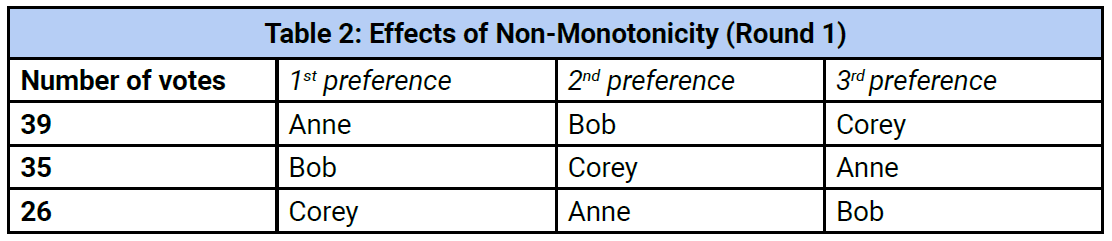

In some cases (such as a tight three-way race), ranked-choice voting violates this principle, meaning that more first-place votes can hurt, rather than help, a candidate.[39] To see how non-monotonicity works, consider the following example:

Suppose three candidates, Anne (A), Bob (B), and Corey (C) are running for Congress. For simplicity, assume only 100 ballots are cast. Therefore, the number of ballots needed to win is 51 (assuming no exhausted ballots). The results are shown below.

No candidate has a majority of the vote, so the last-place finisher, Corey, is eliminated. His 26 votes go to Anne, who wins in the second round with 65 of the 100 votes (her original 39 votes plus the 26 votes she gained when Corey was eliminated).

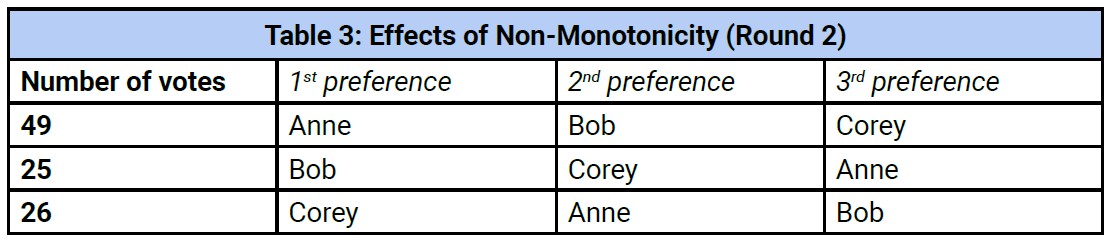

Now suppose that prior to the election, sensing that Anne was the strongest candidate, 10 of Bob’s voters had shifted their first-place preference to Anne. The table below shows the distribution of ballots.

Under this scenario, Anne falls just short of a majority in the first round. Bob finishes last, so he is eliminated; his 25 votes go to Corey, who carries the election with 51 votes (his original 26 votes plus the 25 votes he gained when Bob was eliminated). Anne received more first-place votes than in the first scenario, but this increase in support turned her victory into defeat.

The 2009 mayoral election in Burlington, Vermont shows that non-monotonicity is not merely a theoretical danger. The three-way race pitted Progressive Bob Kiss against Democrat Andy Montroll and Republican Kurt Wright. Bob Kiss won the election, but he could have lost if more Wright voters had ranked Kiss first, causing Montroll to come in second place in the first round. Then Montroll would have gained enough votes from Wright in the second round to defeat Kiss.[40]

Another important result from Burlington’s 2009 mayoral election is that the candidate who was preferred over all other candidates in a head-to-head race, Andy Montroll, lost the election via ranked-choice voting. This demonstrates the issues caused by a non-monotonic voting system.[41]

Ranked-Choice Voting and Third-Party Candidates

Alaska has always had a strong independent political streak, and encouraging third-party involvement in policymaking is a goal many Alaskans share. Plurality elections are often accused of stifling third-party candidates and shutting unorthodox voices out of the political process, forcing voters to choose between throwing away their vote on a long-shot candidate or helping to elect a more viable candidate who doesn’t as accurately reflect voters’ preferences.

While this is certainly a weakness of plurality elections, ranked-choice voting is not an obvious improvement. In fact, ranked-choice voting can neuter third parties and help to perpetuate the two-party system that many voters dislike. Despite proponents’ claims, ranked-choice voting does not solve the “spoiler” problem, where voters are reluctant to rank their favorite candidate first for fear of letting their least favorite candidate win.[42]

There are only two cases in which ranked-choice voting lets you rank your favorite candidate first without worrying about a spoiler effect. First, when your favorite candidate is the clear winner. Second, when your favorite candidate is clearly going to lose (and your second-choice vote for a compromise candidate will be tabulated in the second round). In between these two extremes, ranked-choice voting doesn’t solve the spoiler problem.

Ranking a strong third-party candidate first, for example, may get your compromise candidate eliminated, causing your least-favorite candidate to win. In this scenario, ranking the compromise candidate first might have buttressed his support enough to win outright or survive a second-round matchup with your least-favorite candidate. In short, voters in ranked-choice voting elections still have to worry about spoiler effects and may still feel pressure not to rank their true favorite candidate first.

Ranking a strong third-party candidate first, for example, may get your compromise candidate eliminated, causing your least-favorite candidate to win. In this scenario, ranking the compromise candidate first might have buttressed his support enough to win outright or survive a second-round matchup with your least-favorite candidate. In short, voters in ranked-choice voting elections still have to worry about spoiler effects and may still feel pressure not to rank their true favorite candidate first.

In addition, much of third parties’ power in the U.S. derives not from the number of elected positions they hold, but from their ability to influence major party candidates to cater to “ideological minorities.” Jason Sorens, a lecturer at Dartmouth College, outlines the loss of third parties’ “blackmail power” as a disadvantage of instant run-off voting because it allows major party candidates to ignore third party constituencies.[43]

In plurality elections, Republican candidates, for example, may adopt more Libertarian positions than they would otherwise in order to buttress that small but potentially important constituency. Similarly, Democratic politicians may find it in their interest to defend more environmentally centered positions to appeal to Green Party voters. Third parties can strategically run candidates in specific districts in order to “punish” a major-party candidate. A Libertarian candidate, for example, may challenge a Republican who is viewed as too distant from Libertarian goals, splitting the vote and causing the Republican to lose an otherwise-winnable election.[44]

However, under ranked-choice voting, third parties’ “blackmail power” is significantly eroded, since major party candidates can usually be confident of inheriting the votes of an ideologically similar third-party challenger who is eliminated in the early rounds of tabulation.

Therefore, ranked-choice voting should not be celebrated as a victory for third-party candidates. In fact, it may hurt them because it weakens their ability to push major-party candidates to support more moderate, or extreme, policies.

Jurisdictions That Have Repealed Ranked-Choice Voting

A handful of jurisdictions have adopted, tested, and subsequently repealed ranked-choice voting or instant run-off election systems. These jurisdictions are identified and described below. In addition, there have been multiple efforts in Maine to overturn or amend its ranked-choice voting system.

Burlington, Vermont

The City of Burlington adopted ranked-choice voting for mayoral races in 2005 and implemented the new voting system in 2006. It was used in two mayoral elections and was subsequently repealed by nearly 52 percent of voters in 2010.[45] The repeal might have been due to voters’ discontent with an unpopular incumbent winning reelection in 2009 with only 29 percent of first-place votes.[46]

Ann Arbor, Michigan

An initiative organized by the Human Rights Party (HRP) establishing the use of ranked-choice voting in mayoral elections was approved by Ann Arbor voters in 1974. According to an email from an election clerk in Washtenaw County, Michigan, typical elections in the city would play out like this: “the Republican candidate would get the most votes, but the Democrats and HRP would together have a majority.” Because of this dynamic, “the Democrats and the HRP worked together to create the ranked choice plan.”

After a mayoral election in 1975, Republicans started a petition drive to repeal ranked-choice voting. In 1976, 62 percent of voters cast their ballot in favor of repealing ranked-choice voting.[47] Thus, Ann Arbor residents repealed the voting system after their first experiment with it.

State of North Carolina

The State of North Carolina adopted ranked-choice voting for judicial vacancies in 2006. In 2010, only two races, a statewide Court of Appeals and a district-wide Superior Court race, resulted in more than one round of counting that triggered ranked-choice voting. According to a local news station in North Carolina, the voting system had “mixed reviews” from voters when it was used in 2010.[48]

In 2013, the election system was repealed through HB 589, a voter ID bill that passed in the North Carolina General Assembly and made several changes to the state’s election law.[49] Therefore, the legislature decided to repeal the law three years after it was used in a statewide judicial race.

Aspen, Colorado

After Aspen used ranked-choice voting for the first time in 2009, voters rejected the voting system in 2010 with approximately 65 percent of the vote.[[50]] Curtis Wackerle, an editor for the Aspen Daily News, estimates that voters repealed ranked-choice voting because, “in the four municipal elections in which it was used, the candidate who received the most votes in the first round won the runoff every time, making the extra month of campaigning seem like a money-sucking, brain damage-inducing waste of time.”[51]

Pierce County, Washington

Voters in Pierce County Washington adopted ranked-choice voting to elect county officials in 2006, with 53 percent of voters approving the system.[52] Voters who participated in an auditor’s survey indicated they did not like the voting system by a 2-1 margin. According to the Washington Secretary of State, voters repealed ranked-choice voting with 71 percent of the vote in 2009.[53] Elections Director Nick Handy had this to say about ranked-choice voting in Pierce County:

Just three years ago, Pierce County voters enthusiastically embraced this new idea as a replacement for the then highly unpopular Pick-a-Party primary. Pierce County did a terrific job implementing ranked choice voting, but voters flat out did not like it.

The rapid rejection of this election model that has been popular in San Francisco, but few other places, was expected, but no one really anticipated how fast the cradle to grave cycle would run. The voters wanted it. The voters got and tried it. The voters did not like it. And the voters emphatically rejected it. All in a very quick three years.

It is clear that voters in these jurisdictions felt that their traditional voting method, whatever it may have been, was superior to ranked-choice voting.

Potential Expansion

While ranked-choice voting was originally used only in federal and primary elections in Maine, there are ongoing efforts for it to be used in presidential primaries and general elections as well.[54] There are also ongoing efforts in several other states. These include Alaska, Massachusetts, North Dakota, and Arkansas.[55] In addition, San Diego, the eighth largest city in the country, recently considered ranked-choice voting at the city level. However, the city council rejected the idea, arguing that instituting ranked-choice voting “would confuse voters, increase election costs, and possibly have unintended consequences.”[56]

Conclusion

Democratic choice, within the confines of our constitutional republic, forms the bedrock of America’s system of governance. Adopting a simple, fair, and secure voting system is fundamental to democratic elections. It is clear that plurality elections are much simpler and easier to understand than races determined by ranked-choice voting.

This analysis of 96 ranked-choice voting elections from across the country shows that the voting system produces false majorities, frequently exhausts more than 10 percent of ballots cast on Election Day, and further disenfranchises voters who are already less likely to vote.

While proponents of ranked-choice voting may claim the new voting system is a better alternative to traditional voting systems, the plurality system offers voters an easier method of selecting representatives without the false promises of ranked-choice voting.

**********

This report was published in conjunction with the Maine Policy Institute (MPI). MPI is a nonpartisan organization that conducts detailed and timely research to educate the public, the media, and lawmakers about public policy solutions.

Endnotes

1 “Ranked Choice Voting in US Elections.” FairVote. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.fairvote.org/ranked_choice_voting_is_a_victory_for_san_francisco_voters.

[2] “Voting in Maine’s Ranked Choice Election.” Town of Wiscasset. 2018. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.wiscasset.org/uploads/originals/rankchoicevoting.pdf.

[3] Oliphant, J. Baxter. “Many Voters Don’t Know Where Trump, Clinton Stand on Issues.” Pew Research Center. September 23, 2016. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/23/ahead-of-debates-many-voters-dont-know-much-about-where-trump-clinton-stand-on-major-issues/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “What’s in a Name? One-third of US Voters Don’t Know Candidates.” CNBC. October 03, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/03/one-third-of-us-voters-dont-know-candi-dates-reutersipsos-poll.html.

[6] Ahler, Douglas, Jack Citrin, and Gabriel S. Lenz. “Why Voters May Have Failed to Reward Proximate Candidates in the 2012 Top Two Primary.” California Journal of Politics and Policy. January 15, 2015. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9714j8pc.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “2018 General Election Results.” Maine Secretary of State. 2018. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/elec/results/results18.html#Nov6.

[9] Portland, Maine 2011 Mayoral Election Results. FairVote. 2011. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.slideshare.net/kkellyfv/portland-me-2011-mayoral-election-graphs-1.

[10] Burnett, Craig M., and Vladimir Kogan. “Ballot (and Voter) “exhaustion” under Instant Runoff Voting: An Examination of Four Ranked-choice Elections.” Electoral Studies. November 18, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379414001395.

[11] “Official Ranked-Choice Results Report November 2, 2010 Consolidated Statewide Direct Primary Election Board of Supervisors, District 10.” City of San Francisco. 2011. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://sfelections.org/results/20101102/data/d10.html.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Neely, Francis, Lisel Blash, and Corey Cook. “An Assessment of Ranked-Choice Voting in the San Francisco 2004 Election Final Report.” FairVote. May 2005. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://archive.fairvote.org/sfrcv/SFSU-PRI_RCV_final_report_June_30.pdf.

[14] “English (About Language Assistance).” Alaska Division of Elections. Accessed August 6, 2020. https://elections.alaska.gov/Core/EnglishLanding.php.

[15] McDaniel, Jason. “Ranked Choice Voting Likely Means Lower Turnout, More Errors.” Cato Unbound. December 13, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.cato-unbound.org/2016/12/13/jason-mc-daniel/ranked-choice-voting-likely-means-lower-turnout-more-errors.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Spoilage and Error Rates with Range Voting versus Other Voting Systems.” RangeVoting.org – Experimental Ballot Spoilage Rates for Different Voting Systems. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://rangevoting.org/SPRates.html.

[19] “Benefits of Ranked Choice Voting.” FairVote. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.fairvote.org/rcvbenefits.

[20] “2018 Second Congressional District Election Results.” Maine Secretary of State. 2018. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/elec/results/2018/updated-summary-report-CD2.xls.

[21] Burnett, Craig M., and Vladimir Kogan. “Ballot (and Voter) “exhaustion” under Instant Runoff Voting: An Examination of Four Ranked-choice Elections.” Electoral Studies. November 18, 2014. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379414001395.

[22] “What Data Exists to Support the Argument That Ranked Choice Voting Has Reduced Negative Campaigning in Jurisdictions Where It Has Been Adopted?” The Committee for Ranked Choice Voting 2020. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.rcvmaine.com/what_data_exists_to_support_the_argu-ment_that_ranked_choice_voting_has_reduced_negative_campaigning_in_jurisdictions_where_it_ has_been_adopted.

[23] Tolbert, Caroline. “Experiments in Election Reform: Voter Perceptions of Campaigns Under Preferential and Plurality Voting.” University of Iowa. March 15-16, 2014. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/caroline-tolbert.pdf.

[24] Title 21-A, §1019-B: Reports of Independent Expenditures. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/statutes/21-A/title21-Asec1019-B.html.

[25] “Candidate Elections.” Maine.gov. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.maine.gov/ethics/candidates/disclosure.

[26] “Independent Expenditure Reports 2018 Primary Election.” Maine Commission on Ethics & Election Practices. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.maine.gov/ethics/candidates/disclosure/2018primaryelection.

[27] “Maine’s 2nd Congressional District Election, 2018.” Ballotpedia. Accessed August 10, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/Maine%27s_2nd_Congressional_District_election,_2018.

[28] DeSilver, Drew. “U.S. Voter Turnout Trails Most Developed Countries.” Pew Research Center. May 21, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/21/u-s-voter-turnout-trails-most-developed-countries/.

[29] “Voter Turnout in United States Elections.” Ballotpedia. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://ballotpedia.org/Voter_turnout_in_United_States_elections.

[30] Henry, Madeline Alys. “The Implementation and Effects of Ranked Choice Voting in California Cities.” 2016. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://csus-dspace.calstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10211.3/182785/Henry.pdf.

[31] Ganapathy, Vignesh. “Written Testimony.” October 27, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://www.aclukansas.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/aclu_testimony_on_ranked_choice_voting.pdf.

[32] Kimball, David, and Joseph Anthony. “The Adoption of Ranked Choice Voting Raised Turnout 10 Points.” FairVote. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/fairvote/pages/426/attachments/original/1449182124/Kimball-and-Anthony-one-pager-27-Oct.pdf?1449182124.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] McDaniel, Jason. “Ranked Choice Voting Likely Means Lower Turnout, More Errors.” Cato Unbound. December 13, 2016. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cato-unbound.org/2016/12/13/jason-mc-daniel/ranked-choice-voting-likely-means-lower-turnout-more-errors.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Neely, Francis, Lisel Blash, and Corey Cook. “An Assessment of Ranked-Choice Voting in the San Francisco 2004 Election Final Report.” FairVote. May 2005. Accessed July 23, 2019. https://archive.fairvote.org/sfrcv/SFSU-PRI_RCV_final_report_June_30.pdf.

[38] Gierzynski, Anthony. “Instant Runoff Voting.” Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.uvm.edu/~vlrs/IRVassessment.pdf.

[39] “Monotonicity and IRV — Why the Monotonicity Criterion Is of Little Import.” FairVote. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://archive.fairvote.org/monotonicity/.

[40] Gierzynski, Anthony. “Instant Runoff Voting.” Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.uvm.edu/~vlrs/IRVassessment.pdf.

[41] Ibid.

[42] “Eliminates the Spoiler Effect.” Utah Ranked Choice Voting. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://utahrcv.com/why-ranked-choice-voting/more-choices-more-voices/.

[43] Sorens, Jason. “The False Promise of Instant Runoff Voting.” Cato Unbound. December 09, 2016. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cato-unbound.org/2016/12/09/jason-sorens/false-promise-in-stant-runoff-voting.

[44] Ibid.

[45] McCrea, Lynne. “Burlington Voters Repeal Instant Runoff Voting.” VPR Archive. December 12, 2016. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://vprarchive.vpr.net/vpr-news/burlington-voters-repeal-instant-runoff-voting/.

[46] Scher, Bill. “Is Ranked-Choice Voting Transforming Our Politics?” RealClearPolitics. June 18, 2018. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2018/06/18/is_ranked-choice_vot-ing_transforming_our_politics_137294.html.

[47] Walter, Benjamin. “Instant Runoff Voting: History in Ann Arbor, Michigan.” Archive.fo. September 17, 2008. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://archive.fo/lc5Ww.

[48] Binker, Mark. “Q&A: Changes to NC Election Laws.” WRAL.com. August 12, 2013. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://www.wral.com/election-changes-coming-in-2014-2016/12750290/.

[49] S.L. 2013-381. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/SessionLaws/HTML/2013-2014/SL2013-381.html.

[50] Wackerle, Curtis. “City Voters Repeal IRV.” Aspen Daily News. December 18, 2017. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://www.aspendailynews.com/city-voters-repeal-irv/article_5d3a9245-bfc1-55db-947b-fefd-b87031ea.html.

[51] Ibid.

[52] “November 7, 2006 General Election – Final Election Results.” Pierce County, Washington. November 28, 2006. https://www.piercecountywa.gov/DocumentCenter/View/1512/nov2006results?bidId=.

[53] Washington Secretary of State’s Office. “Pierce Voters Nix ‘ranked-choice Voting’.” From Our Corner. November 12, 2009. Accessed August 07, 2019. https://blogs.sos.wa.gov/FromOurCorner/index. php/2009/11/pierce-voters-nix-ranked-choice-voting/.

[54] Maine State Legislature. “Legislative Document 1083.” January 12, 2020. https://legislature.maine.gov/legis/bills/getPDF.asp?paper=SP0315&item=4&snum=129.

[55] “Massachusetts Question 2, Ranked-Choice Voting Initiative (2020).” Ballotpedia. Accessed August 14, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/Massachusetts_Question_2,_Ranked-Choice_Voting_Initiative_(2020)#cite_note-2.

“North Dakota Top-Four Ranked-Choice Voting, Redistricting, and Election Process Changes Initiative (2020).” Ballotpedia. Accessed August 14, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/North_Dakota_Top-Four_ Ranked-Choice_Voting,_Redistricting,_and_Election_Process_Changes_Initiative_(2020).

“Arkansas Top-Four Ranked-Choice Voting Initiative (2020).” Ballotpedia. Accessed August 14, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/Arkansas_Top-Four_Ranked-Choice_Voting_Initiative_(2020).

[56] Garrick, David. “San Diego Voters Can Lift 30-foot Height Limit Near Sports Arena in November.” The San Diego Union-Tribune. July 21, 2020. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/politics/story/2020-07-21/san-diego-voters-can-lift-30-foot-height-limit-near-sports-arena-in-november.