By Aubrey Wursten

Introduction

Alaska is one of 35 states still subject to health care certificate of need (CON) laws. These regulations require that certain proposed health care facilities or expansions receive permission from the Alaska Department of Health to begin operating. However, contrary to normal licensing procedures, approval is based not on the qualifications of the facility or its workers, but on the judgment of the government that the new or expanded facility is needed in the proposed area.

To make this decision, the Department of Health relies on input from existing local health care entities — the new or expanding organization’s competitors — rather than potential patients’ desire for another option.

Unsurprisingly, many health care facilities, such as hospitals, in Alaska are shuttered before they can even begin caring for patients. Just as Alaskans’ might doubt the prospects for a new Carl’s Jr. if the company required the approval of a nearby Burger King, new health care facilities struggle to convince existing facilities that they are needed.

The first legislators to enact CON laws in the country did so with the intent to save patients money and provide greater access to health care, but the policy failed by these metrics almost as soon as it was implemented. Subsequent enactment in most other states, including Alaska, was then compelled by the federal government. States that are now subject to CON laws suffer an average of five percent higher spending for physician care. Alaska, itself, holds the dubious distinction of having the highest health care spending in the country. Which is no wonder, as its health care costs are about double the national average

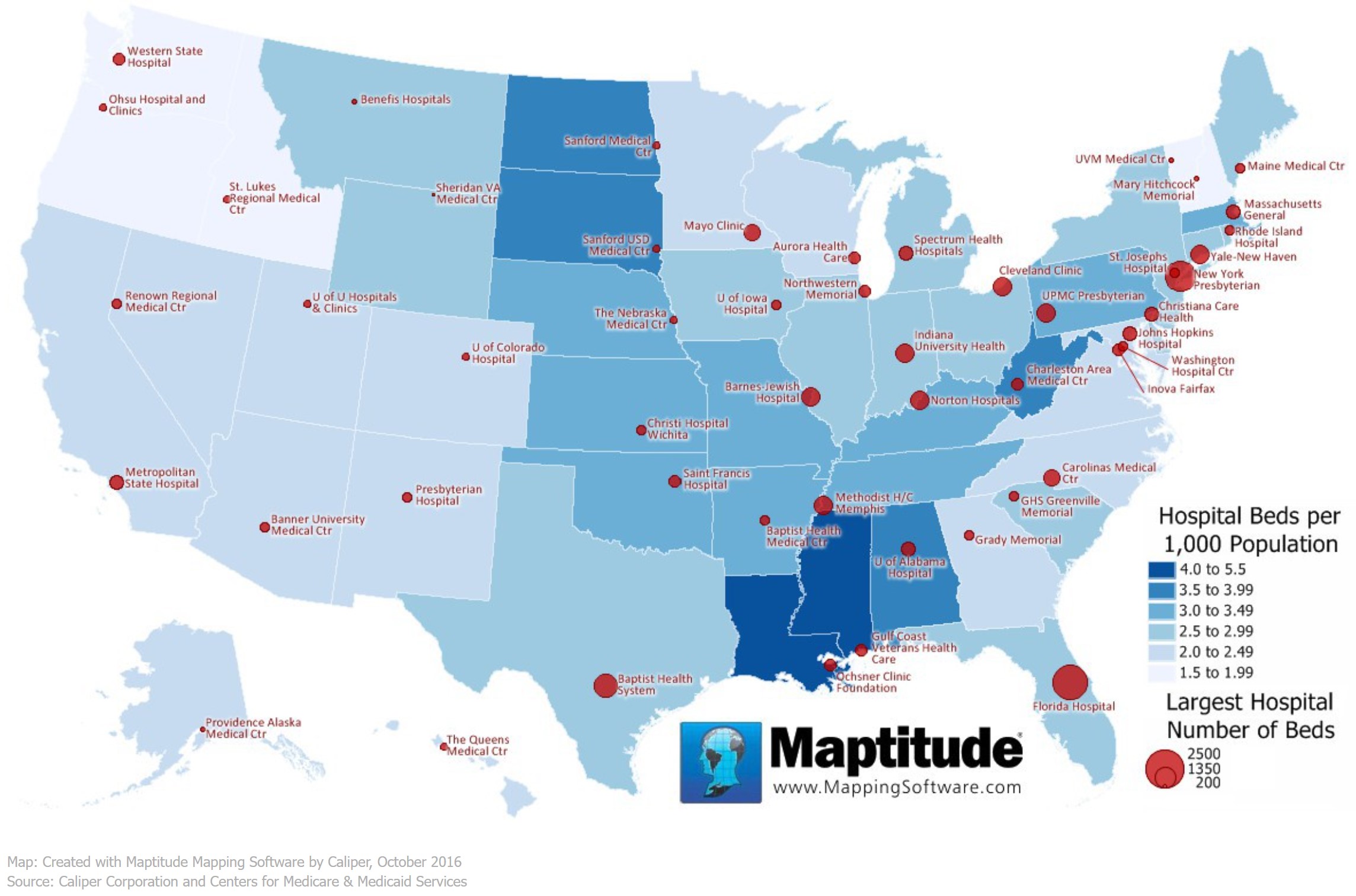

Alaska ranks 33rd on the list of states for hospital beds per capita, with 2.17 beds per 1,000 residents (see Figure 1). In contrast, South Dakota, which does not have CON laws, is at the top of the list, with 4.82 beds per 1,000 residents.

Figure 1.

Source: Caliper Corporation and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

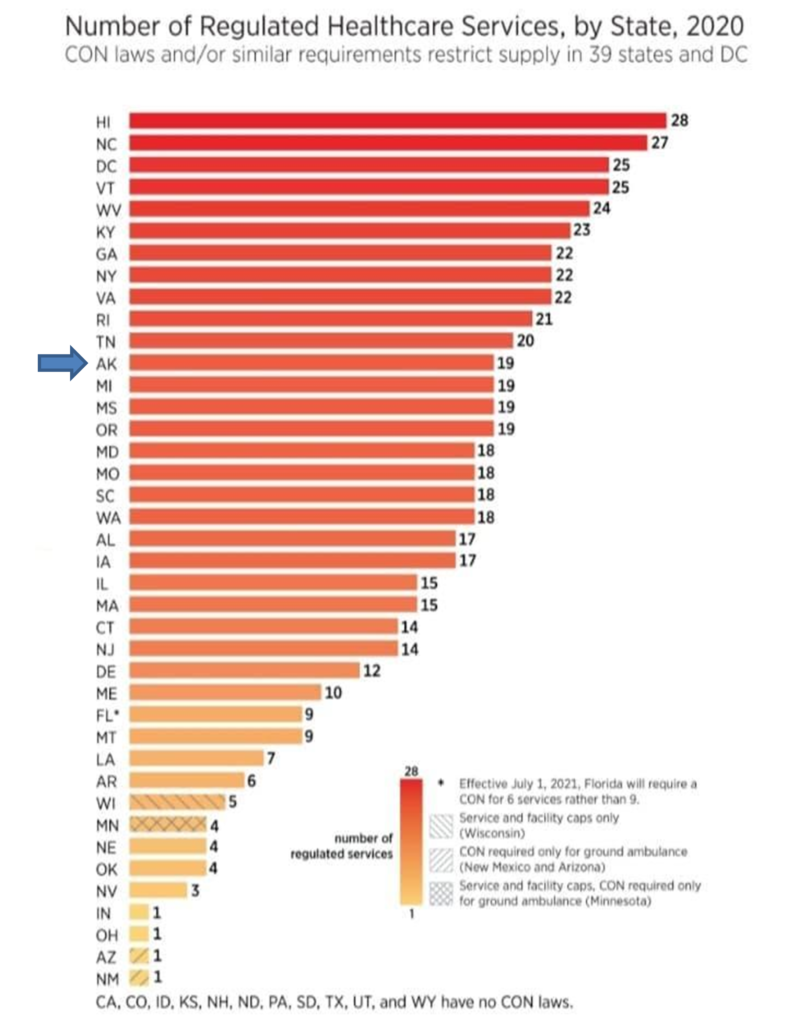

Alaska ranks number one among all 50 states in health care expenditures and 12th for the number of CON regulations. Alaska’s CON code book is 28 pages long. Although many factors contribute to the health care price dilemma, implementing CONs has only made the problem worse. The goal of increasing access to health care in Alaska has not been achieved, and health care prices have not decreased.

Many initial supporters have realized that CON laws have not produced the intended outcomes. Numerous medical professionals and government policymakers across the political spectrum have sought to reverse them, but these opponents have thus far had little success in Alaska. The Alaska Department of Health continues to insist that its oversight is necessary to ensure health care facilities are “planned properly.”

This report examines the initial justification given for CON laws and explores the inherent flaws in the logic behind them. It also provides some of the statistics and stories reinforcing the conclusion that the laws have, indeed, proven counterproductive. CON laws have neither decreased health care prices nor increased access to care. The report explains some reasons CON laws have not yet been repealed in Alaska despite the great toll they have taken. Finally, the text provides a path toward the reversal of what the American Medical Association (AMA) calls “a failed public policy.”

History and Initial Reasoning

In 1964, officials in the state of New York expressed concern about rising hospital costs, and they postulated that the increase was caused by the over-proliferation of hospitals themselves. Their rationale was that, if not enough patients needed health care services to fill the beds, the facilities would distribute the high cost of overhead with inflated prices for each patient. These hefty charges would, in turn, price some patients out of access to health care. To combat the problem of health care costs and control access to hospitals, New York officials passed the Metcalf-McCloskey Act, which required anyone desiring to build a new hospital in the state to receive government permission.

As a New York Times article explained at the time of the act’s passage, “Anyone who could raise or borrow enough money was entitled to construct new hospital facilities without having to justify the public need for them. To correct and control this situation the Metcalf-McCloskey Act provided for review of proposed new hospital facilities by a state council and its affiliated regional agencies.”

A decade later, the Times reported that New York City’s health care budget had actually increased by three and a half times since the passage of the law. That same year, the U.S. Congress inexplicably strong-armed all other states into adopting similar laws. The sweeping National Health Planning and Resources Development Act (NHPRD) of 1974 mandated states to implement their own CON laws as a condition of receiving federal Medicaid or Medicare funds. As in most other states (excluding Louisiana), the desire for federal funding compelled Alaska to implement its own CON legislation. And along with the rest of the country, Alaska saw its health care expenditures grow even more quickly (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Source: Petersen-KFF Health System Tracker

A Glaring Error

The most glaring attribute of the CON “solution” to the problem of excess costs and decreased supply is its overt rejection of the principle of supply and demand. Standard economics observes that when the supply of a product or service increases, the cost decreases and vice versa.

Ideally, with numerous comparable options, customers needing non-emergency care choose the least-expensive option that meets their needs. This inevitability forces businesses — such as hospitals or doctors’ offices — to lower prices to competitive levels. So, if Hospital A charges significantly more than Hospital B, Hospital A must either lower its costs or go out of business.

If the latter occurs, Hospital B becomes a monopoly, leading to higher costs and lower access for everyone. As the Mercatus Center at George Mason University notes, “Economic theory holds that if supply shrinks and demand remains steady, prices will increase.” This equation renders the local health care industry more lucrative, with customers exceeding the capacity of providers, which attracts competitors to fill the needs of the most underserved areas, which competition, in turn, drives prices back down.

But prices only decrease — and access only increases — if competitors are allowed to operate. Unfortunately in Alaska, due in part because of CON laws, citizens do not have numerous comparable care options and care facilities have few incentives to lower their prices.

The Original CON Flaw

Despite the obvious faults in the logic, proponents of CON laws justify government interference by insisting that health care was too important to entrust to basic economic principles. “The vital need for healthcare services requires that such services always be available to the community, and not be subject to the typical ebb and flow of a free market,” insists one trio of advocates. However, the architects of CON laws have never explained why hospital proprietors would, uniquely among enterprises, mis-invest, why consumers would inexplicably pay higher prices if they did, or why competitors would fail to seize the opportunity and fill the void in a sparse (and lucrative) marketplace.

Perhaps the lack of explanation indicates that none of these outcomes is likely. Although CON laws themselves are relatively obscure, an even lesser-known fact exists hidden in their history, and it shows errant logic right from the beginning: The reasoning behind CON laws was based not on the principles of a free market, but on the imperative for a market controlled by the government.

Because hospitals were built and funded largely with tax dollars, the health care administrators responsible for allocating that money predictably spent more freely than they would have were they business owners risking their own resources. With a virtual blank check and no personal stake in the business, they had no incentive to spend wisely.

The NHPRD of 1974 even states, “The massive infusion of Federal funds into the existing health care system has contributed to inflationary increases in the cost of health care and failed to produce an adequate supply or distribution of health resources, and consequently has not made possible equal access for everyone to such resources.”

As former Federal Trade Commissioner (FTC) Maureen K. Ohlhausen put it, “Proponents viewed state intervention as a necessary check on a perceived market failure created by the existing reimbursement structure.”

In other words, the impetus for CON laws derived from a problematic situation that government caused, and the legislators’ solution was more government involvement. Again, the distance between their actions and any personal risk allowed the laws’ drafters to base the policy on concepts that economist Dr. Matthew Mitchell stated “wouldn’t pass muster in Econ 101 class.”

Repeal

By 1982, less than a decade after enacting the NHPRD, the federal government was already concerned that it had made a mistake. Legislators from all sides agreed it should be repealed, and in 1986, a bipartisan majority of Congress decided to abolish the CON mandate. Rep. Roy Roland (D-Ga.), himself a physician, recommended that Congress go further, saying, “It’s now time to abolish it throughout the nation.”

The AMA, an early proponent of the law, also withdrew its support, and a 2004 joint study by the FTC and Department of Justice (DOJ) likewise found that “such programs are not successful in containing health care costs, and they pose serious anticompetitive risks that usually outweigh their purported economic benefits.” The National Conference for State Legislators (NCSL) created a comprehensive summary of CON laws’ history and concluded that “highly concentrated hospitals and other health care facilities may charge more for health services, leading to an overall increase in health care spending.”

Despite the complete reversal of both experts and the federal government itself, the legislatures of 35 states — including Alaska — have thus far declined to take their advice, as shown in the number of states with CON laws in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Source: Mercatus Center

Statistics

Although the rationale behind CON laws was enough for analysts to doubt their effectiveness, their actual results leave little doubt that they have had a negative effect. Consider just a few relevant numbers comparing the remaining 35 CON states to the 15 that have permanently withdrawn them:

- Even after controlling for other factors, states with any CON laws have almost 100 fewer hospital beds per 100,000 residents.

- States with CON laws that specifically target hospital bed numbers fare even worse, with 131 fewer hospital beds per 100,000 residents.

- CON states have approximately half of the number of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines per resident.

- CON areas have an average of 14% fewer total ambulatory surgical centers.

- States with CON rules have lower numbers of hospice care facilities, dialysis clinics, and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) per capita.

- Cost per service is higher in CON states, with any lower overall cost per capita attributable to lower access to care and the resulting reluctance of the population to seek medical help.

- CON laws increase overall health care spending by 3.1% and Medicare spending by 6.9%.

- When states repeal CON laws, they see a 4% drop in health expenditures over five years.

- Of the 10 states with the lowest life expectancies, all but one have CON laws, and many have some of the most restrictive ones in the country.

- Of the 15 states that have repealed their CON regulations, all have seen a reduction in health care costs and hospital readmissions, with no decrease in charitable care.

Real Consequences

A deeper look at the situation reveals the human toll behind the numbers:

- A premature infant died at a hospital in Salem, Virginia, after the hospital was prevented from adding a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) due to competition objections from another neonatal hospital. (This tragedy did not result in any change.)

- CON laws in Michigan limited cancer patients’ access to lifesaving chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, based on resistance from an existing health company that did not want the competition.

- In Kentucky, new home health agencies are allowed in only six of the state’s 120 counties because of the lobbying efforts of $2 billion Baptist Health, which has its own home health agency.

- Med Center in Kentucky, which has a monopoly on emergency medical services (EMS), has prevented any new ambulance companies from opening, despite a life-threatening shortage.

- In Nebraska, aides who can take patients to the grocery store for food cannot legally take them to the pharmacy within the very same store because of ambulatory CON laws.

- CON laws prevented Jay Singleton, a North Carolina ophthalmologist, from opening a reasonably priced outpatient surgery facility, forcing him to perform surgeries at the drastically inflated hospital cost.

- Hope Women’s Cancer Center in North Carolina was forbidden from purchasing its own MRI scanner because it was deemed unnecessary.

Alaska’s Unique Need

One justification for Alaska’s CON laws focuses on the need for better health care access and prices in rural and disadvantaged communities, which is particularly relevant in this unique state. However, for the reasons discussed above, the legislation has rendered care even less available to and more expensive for these very communities.

Writing about health care for The Atlantic, Vann Newkirk notes that Alaskans are “more likely to live in remote areas and more likely to be people of color than those in the continental United States. … Alaska is a unique state, and its combination of naturally high costs, rurality, and remoteness is not replicated anywhere in the continental United States.”

Alaska is geographically more than twice the size of Texas, yet Texas has 83 times more people per square mile. Even under ideal circumstances, Alaskans are naturally going to suffer unusual burdens to reach health care facilities. When those challenges are compounded with the fact that they have fewer than half the number of hospital beds per capita than some other states, the deficit and the danger increase dramatically.

Alaska also has a far higher cost of living than most other states, meaning that each dollar earned must stretch more. Per-person health care expenditures in the state are already more than $2,000 above the national average. The need to lower prices and harness market forces is therefore even more desperate.

A Note About COVID

Many states with CON laws have been rethinking their position since the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only did CON states already have fewer resources at the start of the emergency, but increased red tape prevented them from opening and stocking facilities quickly enough to adjust to the patient influx. Dr. Anne Zink, Alaska’s chief medical officer, admitted, “Our hospitals have been and continue to be incredibly stressed. There is not capacity in the hospitals to care for both COVID and non-COVID patients on a regular basis.”

In a clear admission of the root of the problem, 24 CON states — including Alaska — temporarily lifted some of these mandates during the height of the pandemic. One study estimates that states with high hospital bed utilization saved 100 lives per 100,000 residents, for all causes of death, just by lifting CON regulations.

The provisional move gave rise to some hope that Alaska would finally move to a full repeal, but despite the apparent shift during the COVID-19 pandemic, Alaska’s official law has not changed. COVID-19 provided a stark lesson in the deadliness of these rules, and Alaska policymakers would be remiss if they swept this experience under the rug and returned to business as usual.

The Potential Effect of CON Repeal in Alaska

What would happen if Alaska abolished its entire CON code? The Mercatus Center has calculated some of the likely effects:

- The average Alaskan would save $294 per year on overall health care spending.

- MRI services would increase by 2,137, from 5,880 to 8,017.

- The need to travel lengthy distances for MRIs would decrease by 5.5%.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scans would increase by 4,201, from 6,160 to 10,361.

- The need to travel lengthy distances for CT scans would decrease by 3.6%.

- Post-surgery complications would decrease by 5.2%.

- The number of hospitals could increase from 25 to 35.

- The number of rural hospitals could increase from 17 to 24.

Why the Resistance Continues

Despite the noticeably increased pressure of the past several years, incumbent health care companies continue to resist the idea of abolishing CON laws. Owners and administrators of existing companies reap the financial benefits of these laws without facing the chaos they cause. The people profiting most by admitting as many patients as possible are rarely the floor workers rushing to save those patients’ lives.

Just as health care planners working for hospitals initially applauded the introduction of CON laws, those in the industry are zealous to keep them in place. A brief look at the opponents of Alaska’s 2019 SB 1, which would have repealed Alaska’s CON statutes, reveals the prevention of competition to be a blatant motivation:

- Alaska Radiology Associates worried that it would not recoup a $10 million technology investment if new imaging centers were allowed to open.

- The Alaska Nurses’ Association feared that new facilities would “siphon off the revenue-generating services.”

- Imaging Associates complained that the removal of CON laws would force the organization to compete with facilities it considered inferior.

- Providence Health and Services lamented that “boutique facilities will work to increase their customer base” — in other words, that they would lure away Providence’s customers.

Even more shocking is that a CON, itself, is so valuable. Businesses sometimes sell them off as assets during such processes as bankruptcy. A successfully acquired CON is money in the pocket of the bearer.

A Word of Caution

Although hostility to CON laws seems to be increasing as more people become aware of their existence, opponents should exercise prudence when deciding on a different path forward. Policymakers must remember that a government program began the cost problem and a government program seeking to solve the first problem made it worse.

Health care as an issue elicits strong emotions, and with health care prices skyrocketing, the understandable impulse is often to do something. Human beings tend to feel that doing anything is better than doing nothing. But as even this truncated history of CON laws has shown, wrong-headed or short-sighted policies can always make a situation worse.

A Path Forward

What, then, are some judicious ways Alaska can repeal its CON laws without creating more chaos? Some states have chosen to “sunset” these laws by designating future dates at which they expire, allowing the system to prepare for the new legislative landscape over time. Pennsylvania is an example of a state that has accomplished this transition by giving all facilities and treatments previously covered by CONs time to adjust to a new landscape.

Another variation of this idea involves phasing out aspects of a state’s laws one at a time, as states such as Florida and Georgia have done. Alaska has 19 health care products and facilities, from MRI scanners to neonatal intensive care units, that require certificates of need. If removing all of them at once would prove problematic for facilities, removing a few at a time from the list may allow an easier transition.

On the other hand, states have the option of simply repealing their CON laws all at once, remembering that patients have suffered and even died from the lack of care they have caused. When it comes to repeal in Alaska, faster may be better. Eleven states abolished all CON mandates by 1990, and the sky did not fall in any of them.

Whichever path Alaska chooses, the rollback of this “failed experiment” can only be an improvement. Certificate of need laws have continually proven to serve the needs of corporations rather than communities, yet Alaskan policymakers have carried on for 40 years with detrimental laws that are no longer mandated — or even recommended — by the federal government. Policymakers have had ample evidence and opportunity to move forward, and it is high time they do so.

Aubrey Wursten was the Summer 2022 Policy Intern at Alaska Policy Forum. She is currently studying at Brigham Young University-Idaho.