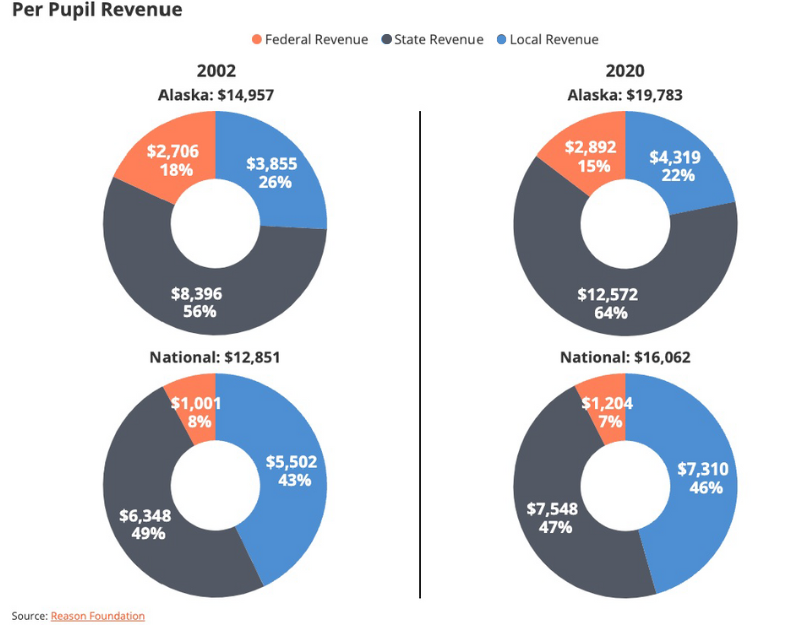

In a previous version of this post, the Per Pupil Revenue figure contained incorrect legend coloring. The legend now correctly shows state revenue in gray and local revenue in blue.

The Reason Foundation recently published the 2022 K–12 education spending spotlight examining school finance trends from 2002 to 2020. The Alaska data points, calculated by the U.S. Census Bureau, show troubling increases in spending fueled overwhelmingly by staff benefits. The data reveals the priority of Alaska has been growing the administration apparatus of schools and districts at the expense of instructing students.

While it is easy to determine overall trends from the data — instruction has been deprioritized in favor of support services, and salaries in favor of benefits — parsing school finance data is difficult and ultimately serves to obfuscate transparency. Although the U.S. Census Bureau is treated as the definitive source of this type of data here, other sources estimate wildly different per-pupil expenditures data. Further, unless members of the public have detailed knowledge of school finances, it is hard to determine which categories encompass what type of expenses. School districts ought to be far more transparent with their finances for policymakers and parents to benefit from understanding how their schools care for their children.

Nationwide Trends

Nationwide trends are worth comparing with Alaska’s trends. Per-pupil education revenue grew in all states except North Carolina. Education revenues represent what is budgeted by the state and what the state must pay for current expenditures, and capital outlay and debt service; because current expenditures exclude capital outlay and debt service from their calculation, revenues are almost always higher than expenditures. Revenues per student grew by 25%, or over $3,000, nationally. Yet between 2002 and 2020, 22 states saw declining student enrollment, including Alaska. The U.S. grew its enrollment by 2% largely because increases in enrollment in some Southern and Western states outweighed plummeting enrollment in many East Coast states.

Across the U.S., spending on employee benefits nearly doubled, from $90 billion to $164 billion per year — an annualized growth rate of about 5%. Salaries grew far more slowly than the increase in benefits, growing from $342 billion to $372 billion for an annualized growth rate of about 0.5%. On a per-pupil basis, spending on total benefits increased by an average of $1,500, while total salaries only grew by $490. Long-term debt grew by about $188 billion — or almost $4,000 per student.

Alaska Trends

In Alaska, total revenue grew 32% per pupil, from $15,000 to $20,000. Sixteen states and D.C. increased their education revenues by 30% or more between 2002 and 2020 after adjusting for inflation. State revenues contributed the most to Alaska’s increase, growing 50% between 2002 and 2020 ($8,000 to $13,000 per pupil). Federal revenue grew only 7% ($2,700 to $2,900 per pupil), while local revenue grew 12% ($3,900 to $4,300 per pupil). In 2002, revenues from the State of Alaska comprised 56% of revenues per pupil, while in 2020, the state contributed 63% of revenues per pupil.

Alaska saw a 0.7% drop in enrollment from 133,000 students in 2002 to 132,000 students in 2020. Yet current spending growth kept pace with revenue growth, increasing 32% per pupil — from $13,800 to $18,300 — adjusted for inflation. While Reason uses U.S. Census Bureau data, other sources tabulate per-pupil spending in Alaska as almost $21,000 based on what districts report directly to the state. The U.S. average for current spending is $16,000 per pupil in 2020. Alaska’s current spending per pupil ($18,300) exceeded the U.S. average by 23%. More remarkable is that two states (Indiana and Idaho) did not increase current spending at all, even after adjusting for inflation. Idaho’s current spending decreased by 3% from 2002 to 2020, while Indiana saw no appreciable difference.

Increasing spending is often seen as the cure-all for a lackluster education system, no matter which state is examined. But higher spending does not necessarily correlate with better outcomes. Alaska had the sixth highest per-pupil expenditures in 2018-2019, yet National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores in 2019 were the fifth lowest nationwide in fourth-grade mathematics and dead last in fourth-grade reading. While Indiana’s current spending stayed constant, it scored seventh-highest in fourth-grade mathematics and 17th in fourth-grade reading. Idaho, while decreasing its spending, scored 15th in fourth-grade mathematics and 11th in fourth-grade reading. This reveals two lessons: high spending doesn’t correlate with good outcomes, and financial data suggests that Alaska’s schools should be adequately funded already. The data below shows how the increases in spending were irresponsibly distributed to activities other than teaching students.

The increase in spending was not distributed equally between salaries and benefits. Salaries increased only 4% per pupil, from $8,300 in 2002 to $8,600 in 2020. Yet total benefits increased 124% per pupil, from $2,400 in 2002 to $5,300 in 2020. Across both instructional and support staff, the increase in salaries over the 18 years of data was meager, yet benefits skyrocketed.

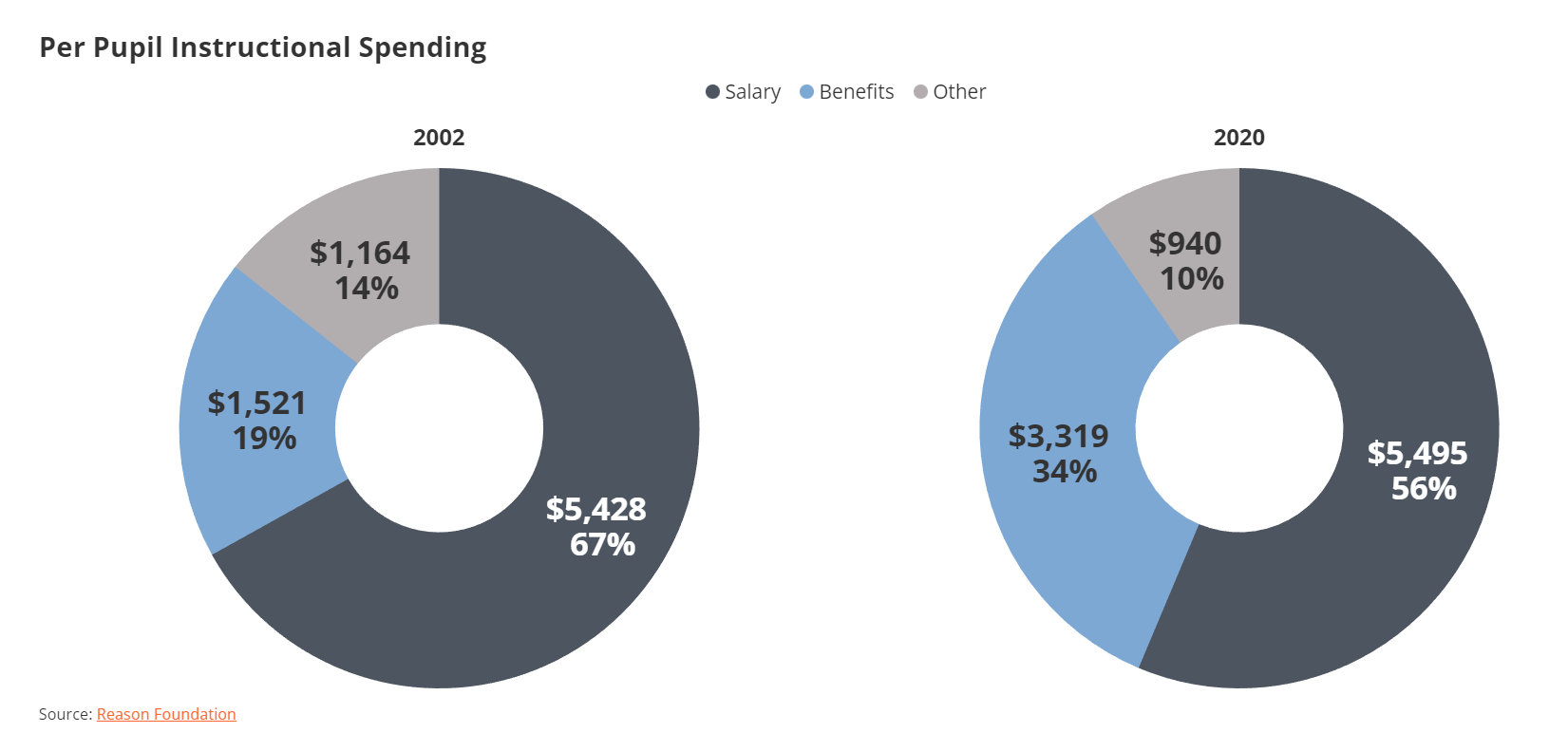

Instructional expenditures, which includes salaries and benefits for teachers, textbooks, supplies, and other purchased services, grew 20% per pupil in Alaska after adjusting for inflation. Per-pupil expenditures were $8,100 in 2002 and grew to $9,800 in 2020. However, instructional salaries per pupil grew only 1%, from $5,400 in 2002 to $5,500 in 2020. Instructional benefits per pupil grew by an astonishing 118%, from $1,500 in 2002 to $3,300 in 2020. Total instructional salaries grew only about $4 million, while instructional benefits grew almost $240 million adjusted for inflation.

Yet the growth in Alaska’s instructional benefits is dwarfed by the growth in support services. Support services includes staff from a wide variety of fields, such as maintenance workers, administration, and transportation. Total spending on support services increased 50% between 2002 and 2020, from $5,300 to $7,900 per pupil. That is 30 percentage points more than the increase in total instructional spending. What’s worse, however, is that growth in support benefits exceeded the growth in support salaries. Support salaries increased 12%, from $2,600 to $2,900 per pupil, while support benefits increased 141% — from $780 to $1,900 per pupil. Support services growth is divided into some common categories and reveals the priorities of Alaska’s education system as it allocated funding between 2002 and 2020.

In Alaska, pupil transportation showed the least growth after adjusting for inflation, increasing only 7% ($540 to $580 per student). Operation and maintenance grew 23%, slightly more than instruction ($1,800 to $2,200 per student) but comprised the largest share of support services spending every year since 2002.

Administrative costs grew between 2002 and 2020, and while general administration did not grow more than instructional expenditures, school administration did. General administration, which includes pay and benefits for superintendents, boards of education, and staff, grew 18%, from $230 to $270 per pupil. This is 2 percentage points less growth than the increase in total instruction expenditures. However, school administration, which includes expenses related to principals’ offices, increased 42%, from $800 to $1,100 per pupil. That is 22 percentage points higher than the increase in total instruction expenditures.

Most support services, however, grew disproportionately compared to instructional expenditures. Pupil support services more than doubled, increasing 107% from $700 to $1,500 per pupil. Reason notes that pupil support services “includes non-instructional items such as psychological, guidance, and healthcare-related expenditures” as well as “paraprofessional services offered to students with disabilities.” Another area of high increases in spending was instructional staff growth, which increased 90%, from $790 to $1,500 per pupil. Finally, the nebulous “Other” category saw an increase of 79% from $420 to $760 per pupil.

However, not all types of spending rose in Alaska between 2002 and 2020. Capital outlays adjusted for inflation decreased 50%, from $2,300 to $1,200 per pupil. Capital outlay declined in 22 states. Debt grew 2% per pupil in Alaska after adjusting for inflation, from $7,000 to $7,140. Total debt, adjusted for inflation, grew 1%, from almost $930 million to $943 million.

Alaska was on a precipitous climb toward higher spending until 2015, which saw significant one-time spending to pay down liabilities in the state’s PERS and TRS retirement systems. In 2015, the state of Alaska made a one-time payment of 528% of the required annual contribution to the unfunded liabilities. As of 2020, Alaska TRS was 73% funded with $2 billion in unfunded benefits for retired teachers — a significant improvement over 2014, which was only 56% funded. Continued savings have also been realized from the state’s switch in 2006 from a defined benefit pension plan, to a 401(k)-style defined contribution plan for state employees.

The Reason data showed peaks in per-pupil revenues and spending in 2015, when the one-time payment occurred. Total revenue peaked at $24,000 per pupil. Instructional spending peaked at $12,000 per pupil, while support services also peaked at $9,000 per pupil. When examining total salary and benefits, it’s clear that the rise in spending was fueled by benefits: in 2002 benefits were only 22% of per-pupil total compensation, while in 2015 benefits were 49% of per-pupil total compensation. By 2020, benefits had rebalanced somewhat to comprise 38%, or $5,000 per pupil. However, the one-time spending could not explain the 124% increase in per-pupil benefits from 2002 to 2020. The U.S. average increase in benefits was 79%, or only $3,000 per pupil.

While paying down TRS unfunded liabilities puts Alaska on the right track, liabilities are still not fully funded as spending on benefits has increased faster than the national average after discounting the one-time spending in 2015.

Since 2002, Alaska grew its education revenues and spending by nearly a third while enrollment has declined. Increases in support services quickly outpaced the lean increases in teaching salaries. Moreover, increases in both instructional and support services were driven primarily by increasing benefits, not salaries. Alaska’s school system prioritized the administrative and support apparatus instead of salaries for teachers.

Those big-picture conclusions are clear, yet school finance data is deliberately difficult to interpret without specialized knowledge of accounting and damages transparency and trust in public schools. School districts should face some transparency requirements to disclose their finances in ways that policymakers and parents can use to understand how schools are educating and caring for Alaska’s children.