Click to open the PDF in a new tab.

Introduction

Many K–12 education advocacy groups in Alaska receive significant amounts of public funding for their internal operations, and dedicate a large share of their focus on securing more public funding for the K–12 system. While those efforts have largely succeeded in increasing the cost of K–12 in Alaska, the additional dollars spent by the state have not improved student outcomes. As a matter of fact, several key student performance measurements have declined in Alaska while the rate of K–12 spending increased significantly above the U.S. average. These K–12 education advocacy groups could improve their influence and credibility with the public and lawmakers if they became more visible advocates for better results for our students.

Many K–12 education advocacy groups in Alaska receive significant amounts of public funding for their internal operations, and dedicate a large share of their focus on securing more public funding for the K–12 system. While those efforts have largely succeeded in increasing the cost of K–12 in Alaska, the additional dollars spent by the state have not improved student outcomes. As a matter of fact, several key student performance measurements have declined in Alaska while the rate of K–12 spending increased significantly above the U.S. average. These K–12 education advocacy groups could improve their influence and credibility with the public and lawmakers if they became more visible advocates for better results for our students.

Education Advocacy Groups

There exists in Alaska today a myriad of advocacy groups which are involved in K–12 public education, both private and public entities. Included are: the Alaska Council of School Administrators, the National Education Association (NEA), the Association of Alaska School Boards, the Coalition for Education Equity (formerly CEAAC, Citizens for the Educational Advancement of Alaska’s Children), the Alaska Association of Secondary School Principals, the Alaska Association of School Business Officials, the Alaska Association of Elementary School Principals, and the American Federation of Teachers. Beyond these organizations, there are 54 school districts, and hundreds of schools within these districts. The common strand between all these non-profit organizations, districts, and schools is that they have historically lobbied for increased K–12 public education funding, with very little emphasis on accountability measures or policies which would improve student outcomes.

A few examples of the public funding streams for some of the more prominent K–12 advocacy groups follow.

In 2016, the Alaska Council of School Administrators (ACSA), an IRS-designated 501(c)(6), collected $160,571 in dues from its members (school district employees) and received $1.4 million in government grants.[1] Government grants are taxpayer money funneled through the school districts, state and federal governments. The mission of the ACSA is clearly stated in its Joint Position Statements—”Adequate funding for public education is our number one priority.”[2] Every one of its policy positions is tied to more funding, including advocating for “additional revenue streams.” Nowhere in its position statements is the improvement of student performance/achievement mentioned.

The NEA-Alaska (NEA-AK) teachers’ union, a 501(c)(5) organization, also participates in the K–12 funding lobby in Juneau. It actively advocates for more funding with little apparent interest in specific programs or ideas to improve student academic performance, as evidenced by its statements to the legislature.[3] In 2016, NEA-AK collected $6.9 million in mandatory dues from its public employee members.[4]

The Association of Alaska School Boards (AASB) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. The mission statement of the AASB is “To advocate for children and youth by assisting school boards in providing quality public education, focused on student achievement, through effective local governance.”[5] Fifty Alaska school districts (of 54 total districts in Alaska) are members of the AASB. In 2017, these school districts paid $547,541 as dues from public sources, and the AASB also received $598,107 in government grants that same year.[6] Individual AASB members also actively participate in lobbying their legislators for more K–12 money: the first legislative priority listed on AASB’s website is regarding funding—not better education.[7]

The Coalition for Education Equity (CEE, formerly CEAAC) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit which has successfully litigated for increased K–12 education funding. As shown on its 2017 IRS filing, CEE collected $145,000 in membership dues, and an additional $171,982 in government grants.[8] Under the CEAAC banner, the organization focused on the perception of school inadequacies in rural Alaska by filing lawsuits asserting inequitable state funding, with two lawsuits being settled in CEAAC’s favor after years of legal wrangling.[9]

The first case, Kasayulie v. State, was based on the concerns of racial discrimination related to inequitable funding of rural schools.[10] In the 2011 settlement, the State of Alaska agreed “to fund $146 million ($481,000 per student) in capital projects for five new schools in Emmonak, Koliganek, Nightmute, Kwethluk and Kivalina, over and above the funding flowing through the (usual) mechanism.”[11] The settlement also included $500,000 in legal fees to be paid to CEAAC from the state.[12] Perhaps most significantly, state law was amended to channel “to rural schools funding equal to 24 percent of school bond reimbursement, … amounting to approximately $38 million annually” as of 2011.[13]

With this additional funding for these five new/renovated schools, there has been no measurable improvement in state test scores. In four of the five schools, 2019 standardized test scores in English language arts (ELA) were dismal: only 5 percent or fewer students were proficient, compared to the statewide average of 39 percent.[14] The fifth, Koliganek School, posted a 9 percent ELA proficiency rate in 2019.[15] In 2011, the state used a different standardized test. In the 2011–2012 school year, Koliganek School posted a 56 percent reading proficiency rate.[16] The cash infusion resulting from the Kasayulie court settlement clearly has not produced the improved educational outcomes those rural students deserve.

The second CEAAC lawsuit, Moore v. State of Alaska, focused on the state’s alleged failure to support and oversee chronically underperforming schools. Its settlement in 2012 resulted in another $18 million of funding “to the 40 lowest-performing schools in the state.”[17] With the funding having been distributed and spent, today only 39 percent of Alaska students statewide are proficient in reading/English language arts.[18]

More Funding Has Not Resulted in Better Outcomes

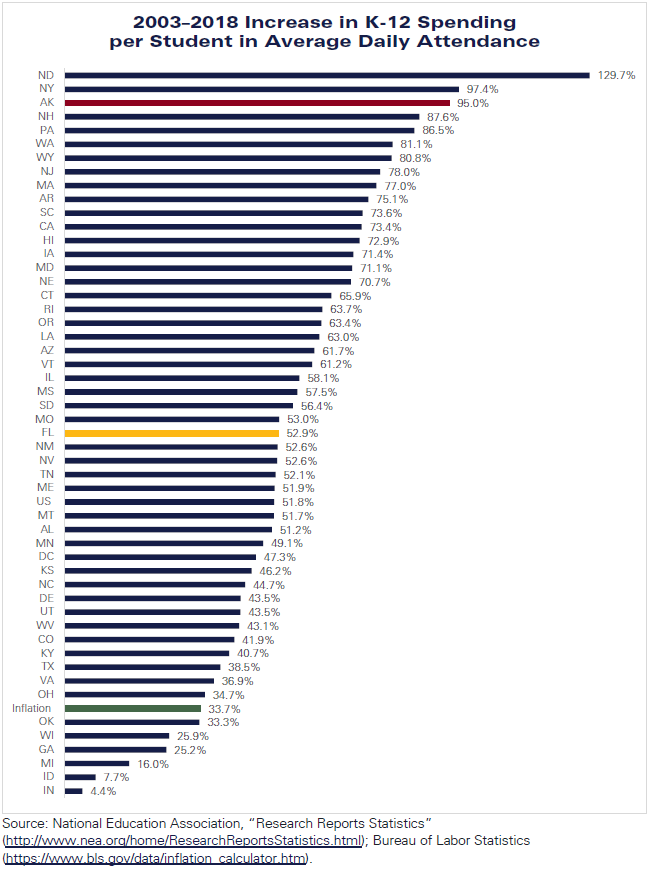

These education advocacy groups have been effective at securing increased funding for Alaska’s K–12 system. According to the National Educational Association’s (NEA) publication Rankings and Estimates, Alaska had the third fastest rate of increase in K–12 spending per student in average daily attendance in the 15 years between 2003 and 2018. During that time period, per student education spending in Alaska increased from $11,233 to $21,907[19]—up 95 percent, nearly triple the 34 percent U.S. inflation rate.[20] The increase in Alaska K–12 spending significantly outstripped the U.S. average of 52 percent during that timeframe: $8,807 in 2002–2003 to $13,368 in 2017–2018[21]. (See Figure 1 for a comparison of all states.)

Figure 1

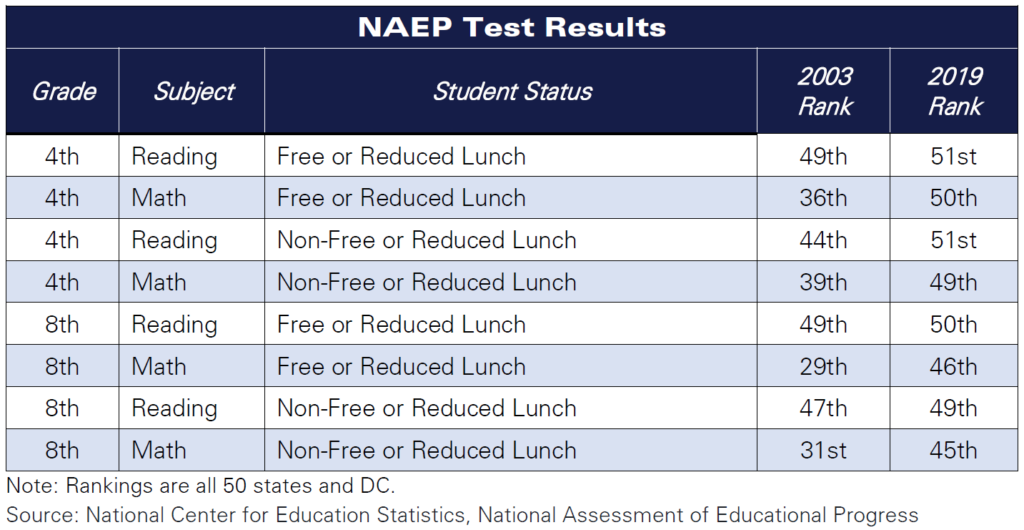

Despite a significant funding advantage over other states, Alaska has continued to produce very disappointing results in national standardized testing. Scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) between 2003 and 2019 showed that Alaska’s combined math and reading standings sank more than any other state—ranking 49th or lower in six of eight categories by 2019. (See Figure 2.)

Alaska’s children are no less intelligent or capable than children in other states; rather, they are being shortchanged by our current K–12 system.

Figure 2

It’s Time to Collaborate on Outcome-Based Solutions

Great progress could be made if Alaska’s K–12 advocacy groups were to come together to begin supporting outcome-based solutions for the crisis of early childhood literacy in Alaska, particularly to include accountability measures. The recently introduced Alaska Reads Act[22] is a great example of a bi-partisan policy that these organizations could line up behind to improve student performance.

The goal of reading intervention programs such as the Alaska Reads Act is to ensure that all students read proficiently by the end of third grade. Students who are reading proficiently when they enter fourth grade are much less likely to require expensive special education referrals during their K–12 education, rely on public assistance as adults, or land in the criminal justice system as adults.[23] In addition, they are likely to have significantly higher lifetime earnings, making them more productive societal contributors compared to poor third-grade readers.[24]

Thirty-seven states have adopted K–3 reading intervention programs; Alaska is one of only 13 states which has not.[25] Most notably, in Florida and Mississippi, the reforms have resulted in rapid improvements in student performance.[26] These programs include multiple components such as early identification of weak readers, creation of special reading plans for weak readers, pairing weak readers with the most effective teachers, use of phonics and evidence-based curriculums, early and continuous parental notification, home reading programs, and school reading programs beyond normal school days. Most importantly, the programs in Florida and Mississippi also utilize proficiency-based promotion, which ensures students have the foundational knowledge they need before they advance through school grade levels.

Proficiency-based promotion allows students to be grouped according to their reading skill level rather than their chronological age. Classes with students who have similar reading abilities are far more effective for students, and far more efficient for teachers. Proficiency-based promotion is the one accountability measure which ensures that weaker readers get the extra time and dedicated attention they deserve to become proficient.

All stakeholders in K–12 education in Alaska should rally behind effective reforms: parents, schools and districts, boards, our legislature, and education advocacy groups. Advocacy groups can contribute significantly to helping Alaska’s K–12 system by refocusing some of their energy on improving educational outcomes, rather than exclusively focusing on more funding. Alaskan children deserve better.

**********

Endnotes

[1] “Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax: Alaska Council of School Administrators.” GuideStar. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://pdf.guidestar.org/PDF_Images/2016/920/073/2016-920073478-0e99c757-9O.pdf.

[2] “Joint Position Statements.” Alaska Council of School Administrators. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.alaskaacsa.org/joint-position-statements/.

[3] Parker, Tim. “NEA-Alaska Letter to Representative Les Gara,” February 19, 2018. https://www.akleg.gov/basis/get_documents.asp?session=30&docid=55992.

[4] “Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax: NEA Alaska Inc.” GuideStar. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://pdf.guidestar.org/PDF_Images/2017/920/022/2017-920022642-0f94fd63-9O.pdf.

[5] “Who We Are.” Alaska Association of School Boards. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://aasb.org/who-we-are/.

[6] “Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax: Association of Alaska School Boards.” Foundation Center. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://990s.foundationcenter.org/990_pdf_archive/920/920098760/920098760_201712_990.pdf.

[7] “AASB Legislative Priorities 2019.” Association of Alaska School Boards. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://aasb.org/aasb-legislative-priorities-2019/.

[8] “Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax: Coalition for Educational Equity.” GuideStar. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://pdf.guidestar.org/PDF_Images/2018/920/162/2018-920162496-108bdad8-9.pdf.

[9] “Alaska.” Education Law Center. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://edlawcenter.org/states/alaska.html.

[10] “CEEAC Legal Activities.” Coalition for Education Equity of Alaska. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.ceaac.net/legal.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “News and Updates.” Coalition for Education Equity of Alaska. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.ceaac.net/news_and_updates.html.

[13] “CEEAC Legal Activities.” Coalition for Education Equity of Alaska. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.ceaac.net/legal.html.

[14] “2018-2019 Negtemiut Elitnaurviat School Results: Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Schoolwide/SchoolwideResult?SchoolYear=2018-2019&IsScience=False&DistrictId=31&SchoolId=310040; “2018-2019 Emmonak School Results: Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Schoolwide/SchoolwideResult?SchoolYear=2018-2019&IsScience=False&DistrictId=32&SchoolId=320040; “2018-2019 Ket’acik/Aapalluk Memorial School Results: Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Schoolwide/SchoolwideResult?SchoolYear=2018-2019&IsScience=False&DistrictId=31&SchoolId=310140; “2018-2019 McQueen School Results: Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Schoolwide/SchoolwideResult?SchoolYear=2018-2019&IsScience=False&DistrictId=37&SchoolId=370060.

[15] “2018-2019 Koliganek School Results: Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Schoolwide/SchoolwideResult?SchoolYear=2018-2019&IsScience=False&DistrictId=45&SchoolId=450050.

[16] “State of Alaska Report Card to the Public – School Level.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/compass/Report/2010-2011/45/450050.

[17] “Alaska’s Rural Districts Settle Lawsuit; Win Additional Funding.” The Rural School and Community Trust, February 23, 2012. https://www.ruraledu.org/articles.php?id=2850.

[18] “2018-2019 Statewide Results: Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools.” Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://education.alaska.gov/assessment-results/Statewide/StatewideResults?schoolYear=2018-2019&isScience=False.

[19] See Figure 1.

[20] “CPI Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

[21] See Figure 1.

[22] “Alaska Reads Act: What and Why?” Office of Governor Mike Dunleavy. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://gov.alaska.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/Alaska-Reads-Act-What-and-Why-01152020.pdf.

[23] “K–3 Reading Communications Tool Kit.” The Foundation for Excellence in Education. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.excelined.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ExcelInEd.K-3ReadingCommunicationsToolkit.Jan2017.pdf.

[24] “Double Jeopardy: How Third Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation.” The Annie E. Casey Foundation, January 1, 2012. https://www.aecf.org/resources/double-jeopardy/.

[25] “Comprehensive K-3 Reading Policy: Fundamental Principles State Analysis.” The Foundation for Excellence in Education, 2018. https://www.excelined.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ExcelinEdPolicyToolkit_K-3Reading_StatebyStateAnalysis_2017-1.pdf.

[26] Griffin, Bob. “Mississippi More than a Year Ahead of Alaska in Fourth Grade Reading.” Alaska Policy Forum, December 4, 2019. https://alaskapolicyforum.org/2019/12/mississippi-alaska-reading/.