Open a printable PDF version of the policy brief here.

Introduction

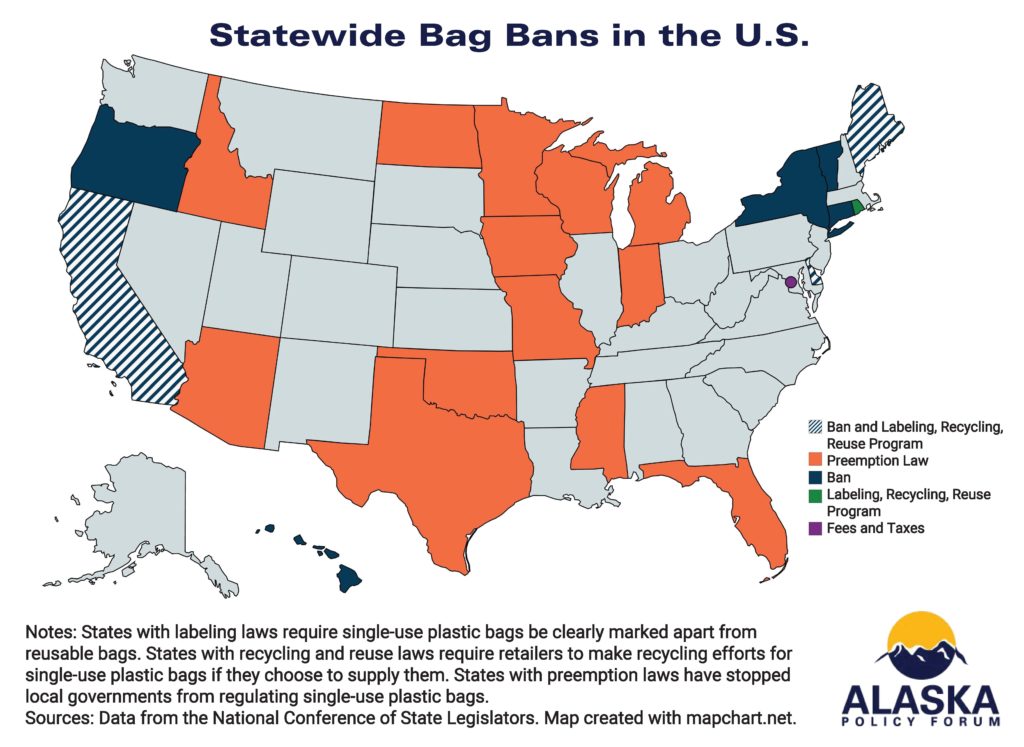

Several Alaskan cities have already instituted single-use plastic bag bans, and more are considering legislation to regulate the use of plastic bags.[1] Figure 1, Citywide Bag Bans in Alaska, shows which Alaskan cities have already instituted plastic bag bans. However, this isn’t an issue specific to Alaska: California and Hawaii have already banned single-use plastic bags statewide, with six other states following suit in 2019 alone, indicated in Figure 2, Statewide Bag Bans in the U.S.[2] If bag bans and taxes work as intended, shopping decisions and behaviors will be directly affected. In order to form an opinion about proposed legislation, it is necessary to know the facts.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Common Misconceptions

Several common arguments in favor of plastic bag bans are fundamentally flawed. Contrary to conventional wisdom, plastic bags are more environmentally friendly than the alternatives consumers would have to adopt during a ban, like paper and cloth bags. These alternatives require more natural resources to produce and transport, so they have a substantially greater carbon footprint than single-use plastic bags – not to mention that paper and cloth bags require much more energy to recycle, if they can be recycled at all.[3] In comparison to paper bags, plastic bags require 70 percent less energy to manufacture and consume 96 percent less water.[4] The situation is even more grim for cloth alternatives; standard reusable cotton grocery bags must be used 131 times to “ensure that they have a lower global warming potential” than plastic bags used only once.[5]

In addition, the term “single-use” plastic diverts attention from the fact that plastic retail bags are frequently used more than once, and in a variety of creative ways. Ninety percent of Americans report using their plastic bags more than once,[6] with 77.7 percent of plastic bags reused as liners for small trash cans.[7] In addition, plastic bags are recyclable, and access to recycling options is expanding for consumers with the installation of collection centers at major grocery chains. There are promising steps being made toward greater recycling of plastic bags, and we should be optimistic about the future of plastic bag waste in landfills.

Ineffective at Best, and Damaging at Worst

Plastic bag bans have been implemented in many cities and states around the country, but there is no convincing evidence that the policy has significantly reduced landfill waste. Plastic bag litter composes less than 2 percent of all litter and only 0.5 percent of landfill waste.[8],[9] Surely if plastic waste needs to be reduced, there are targets with more potential that comprise a larger component of plastic waste. In California, where a statewide ban on single-use plastic bags was imposed in 2016, there was a negligible 0.2 percent decrease in plastic bag litter as a percentage of overall litter.[10]

Plastic bag bans may even increase landfill waste in the long run.[11],[12] When plastic retail bags are banned, consumers need to purchase larger, thicker plastic bags for garbage disposal and animal waste. When these bags are disposed, they take up more room in the landfill and biodegrade less quickly than plastic retail bags.

The Unintended Consequences

Reusable alternatives to single-use plastic bags may have some alarming connections to foodborne illness. A study by the University of Arizona found that 50 percent of reusable cloth bags contained food-borne bacteria, such as salmonella, and 12 percent carried E. coli, indicating the presence of fecal matter.[13] Bacteria build-up on reusable bags may be 300 percent higher than that considered safe,[14] and this is only compounded by storing the bags in a hot car, which incubates the bacteria to grow 10 times faster.[15] In a survey localized to California and Arizona, 97 percent of participants indicated they never washed their cloth bags.[16] When consumers have the option to use plastic bags instead, they can protect their health as well as remove the burden of washing cloth bags for every trip to the grocery store.

The adverse effects of plastic bag bans ripple through local economies. Plastic bag bans hurt small business owners disproportionately through the immediate costs of alternative bags, as well as the unseen cost of regulatory compliance. Stores have to pay extra to provide alternatives to plastic bags, which hurts small businesses that cannot absorb a 40 to 200 percent increase in cost for bags.[17] As Jake Hale, owner of J and J Food Market, stated in public comments on Wasilla’s plastic bag ban, “In a standard month, my small store spends $126 on plastic bags. I pay about a penny a bag. Paper bags are 22 and a half cents a bag, so if I have to get the same amount of paper bags, monthly, that takes me to just under $3,000 a month.”[18] Costs skyrocketing from $126 to $3,000 is an approximate 2,280 percent increase in bag expenses, which small businesses cannot absorb without raising prices, cutting hours, or reducing staff. In addition, for jurisdictions that enforce in-store recycling programs instead of, or in addition to, outright plastic bag bans, the employees that remain will have to use some of their valuable time on bureaucratic procedures to enforce the regulation. It is extremely shortsighted to believe that any small business could be expected to keep its doors open for long after being forced to adopt costly alternatives to “single-use” bags.

In fact, early studies indicate that forcing stores to stop providing “single-use” plastic bags could be driving away business into neighboring regions where the ban is not in effect. The National Center for Policy Analysis conducted a survey in Los Angeles, comparing 80 large stores inside and outside of ban areas, and found that during a one-year period the majority of stores within the ban area reported an overall average sales decline of 6 percent.[19] The stores in areas where plastic bags were allowed reported an average sales growth of 9 percent.[20]

It is always the consumer that bears the cost of regulation. A plastic bag ban means business owners may substitute expensive paper bags, or be unable to provide bags at all, and that cost is ultimately passed to the consumer in either increased prices or increased hassle. Though research on the effects of plastic bag bans is ongoing, it seems that citizens are voting with their feet and indicating that plastic bags provide value to them.

Are Plastic Bag Bans Moral?

Though policy debates primarily focus on the question of practicality and effectiveness, it is important to evaluate the ethics of any government policy before it is implemented. Policies should not violate the freedoms of citizens and overstep the role of government, whether at the local, state, or national level. A plastic bag ban interferes with the consumer’s freedoms and best judgment, which is an important component to a functioning free market. Wasilla Councilmember Tim Burney put it best when explaining his vote against the ban: “I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to dictate to someone who wants to use a plastic bag that they can’t … in a lot of ways that’s the government telling the citizen what to do — again.”[21] It is not the government’s role to dictate what products a citizen can use. Plastic bag bans and bag taxes are only a symptom of greater government overreach into private freedoms and decisions, which must be halted wherever possible.

Conclusion

We encourage Alaskan communities considering a plastic bag ban to fully evaluate the substantial shortcomings and unintended consequences of such a policy. Not only are plastic bag bans ineffective and contradict their intended purpose – it is not the government’s place to dictate to free-trading citizens what products can be bought or sold, nor what type of bags those products can be carried away in.

Endnotes

[1] Grass, Michael. “More Alaska Cities Are Pursuing Local Plastic Bag Bans.” Route Fifty, March 19, 2019. https://www.routefifty.com/management/2018/08/anchorage-alaska-plastic-bag-ban/150583/.

[2] “State Plastic and Paper Bag Legislation.” National Conference of State Legislatures, August 15, 2019. https://www.ncsl.org/research/environment-and-natural-resources/plastic-bag-legislation.aspx.

[3] “Paper vs. Plastic Bags – The Studies.” All About Bags. Accessed September 4, 2019. https://www.allaboutbags.ca/papervplasticstudies.html.

[4] “Plastic Bags and the Environment.” Bag the Ban. Accessed September 4, 2019. https://www.bagtheban.com/learn-the-facts/environment/.

[5] Edwards, Chris, and Jonna Meyhoff Fry. “Life Cycle Assessment of Supermarket Carrier Bags: A Review of the Bags Available in 2006.” U.K. Environment Agency, February 2011. https://www.bagtheban.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/UK-Environment-Study.pdf.

[6] “National Plastic Shopping Bag Recycling Signage Testing.” APCO Insight. American Plastics Council, March 2007. https://www.bagtheban.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/bag-recycling-signage-testing.pdf.

[7] “Environmental and Economic Highlights of the Results of the Life Cycle Assessment of Shopping Bags.” RECYC QUÉBEC, CIRAIG, December 2017. https://www.bagtheban.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Quebec_ENGLISH-LCA-Full-Report.pdf.

[8] Caliendo, Heather. “The Economic Effect of Plastic Bag Bans.” Plastics Today, December 17, 2015. https://www.plasticstoday.com/content/economic-effect-plastic-bag-bans/35843076718443.

[9] “Plastic Bags and the Environment.” Bag the Ban. Accessed September 4, 2019. https://www.bagtheban.com/learn-the-facts/environment/.

[10] “Together For Our Ocean: International Coastal Cleanup 2017 Report.” The Ocean Conservancy, 2017. https://oceanconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-ICC_Report_RM.pdf.

[11] Stockwell, Simon, and Gillian Smith. “Proposed Plastic Bag Levy – Extended Impact Assessment: Research Summary.” UKWA Home. Scottish Government, August 29, 2005. https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20180516073550/https://www.gov.scot/Publications/2005/08/1993102/31039.

[12] Swallow, Julian. “Bin Line Sales Double Nation Average after Plastic Bag Ban.” The Advertiser. August 21, 2011. https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/bin-line-sales-double-nation-average-after-plastic-bag-ban/news-story/5110eb1ecbe8e10e3e18d16e11545940.

[13] Gerba, Charles P, David Williams, and Ryan G Sinclair. “Assessment of the Potential for Cross Contamination of Food Products by Reusable Shopping Bags.” American Chemistry Council, June 9, 2010. https://www.biodeg.org/Arizona University Report.pdf.

[14] Summerbell, Richard. “Grocery Carry Bag Sanitation: A Microbiological Study of Reusable Bags and ‘First or Single-Use’ Plastic Bags.” Environment and Plastics Industry Council, May 2009.

[15] “Plastic Bags Are the Healthier Option – for Families and the Environment.” Bag the Ban. Accessed September 5, 2019. https://www.bagtheban.com/learn-the-facts/health/.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Seattle Public Utilities Plastic Carryout Bag Ban Survey.” Seattle City Clerk. City of Seattle, January 2013. https://clerk.seattle.gov/~public/meetingrecords/2013/luc20130115_3c.pdf.

[18] Hickman, Matt. “Wasilla City Council Votes to Ban Plastic Bags.” Mat-Su Valley Frontiersman, January 9, 2018. https://www.frontiersman.com/community_briefs/wasilla-city-council-votes-to-ban-plastic-bags/article_5ced7aa0-f59d-11e7-a1c0-7f90992587fe.html.

[19] Caliendo, Heather. “The Economic Effect of Plastic Bag Bans.” Plastics Today, December 17, 2015. https://www.plasticstoday.com/content/economic-effect-plastic-bag-bans/35843076718443.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Hickman, Matt. “Wasilla City Council Votes to Ban Plastic Bags.” Mat-Su Valley Frontiersman, January 9, 2018. https://www.frontiersman.com/community_briefs/wasilla-city-council-votes-to-ban-plastic-bags/article_5ced7aa0-f59d-11e7-a1c0-7f90992587fe.html.